Un-Curating the Archive

Infos

Un-Curating the Archive

Based on a Reference Collection by Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch

Part I: 1974 – 1989

Exhibition Preview and Lecture

by Christiane Kuhlmann (curator Museum der Moderne Salzburg)

22.6.2017, 6 pm

more

Opening

23.6.2017, 8 pm

Duration

24.6. – 13.8. 2017

Opening hours

Tuesday – Sunday, 10 am – 5 pm

Participation

Jiri Tomicek and Florian Hofer

Thanks to

Architekturzentrum Wien, Karin Lux

AZW Library, Wolfgang Heidrich

Free Shuttle to the opening

Vienna – Graz – Vienna

Departure Vienna: 23.6.2017, 3 pm, Haltestelle Oper, Bus 59 a

Departure Graz: 23.6.2017, 10.30 pm,

Burgring 2, 8010 Graz

cmrk.org

Intro

In recent years, a series of artistic positions were present—both in the exhibitions of Camera Austria and in the magazine Camera Austria International—which deal with questions related to the archive. So on the one hand, the point is to imagine archives that do not exist but would be necessary, and on the other, to add something to archives that is lacking, that is repressed or excluded. Our surveying of the Camera Austria archive attempts to bring together these different explorative questions. Is it an archive that could add something not yet present to the established narratives about the relevance of contemporary art photography? What other history might it tell? How could it be brought into association with the idea of the “anti-archive” (Peter Friedl)? And how about the uncomfortable question of what power this archive may hold? Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch have developed a publication concept in which all archival material is presented in the exhibition as a reference collection. The archive is reconquering the exhibition space, yet without becoming a veritable exhibition object. It is leaving the file cabinet in order to expose itself to the question of the topicality of its “truth production”.

Read more →Un-Curating the Archive

In short, we need to describe the emergence of a truth-apparatus that cannot be adequately reduced to the optical model provided by the camera. The camera is integrated into a larger ensemble: a bureaucratic-clerical-statistical system of ‘intelligence’. This system can be described as a sophisticated form of the archive. The central artifact of this system is not the camera but the filing cabinet.

Allan Sekula

In 2009, Dieter Roelstraete expressed criticism of the archival or historiographic turn: “The retrospective, historiographic mode—a methodological complex that includes the historical account, the archive, the document, the act of excavating and unearthing, the memorial, the art of reconstruction and reenactment, the testimony—has become both the mandate (‘content’) and the tone (‘form’) favored by a growing number of artists (as well as critics and curators) of varying ages and backgrounds.” According to Roelstraete, a return to the past would signify the disappearance of the future and all utopias.

Perhaps this interest in history has little to do with nostalgia or a post-postmodern return to the “grand narratives”, nor does it primarily involve the loss of the future in a perpetual present that is hopelessly immersed in the analysis of its—fragmented—history. Instead, it may signify a re-evaluation of the construction of the present itself, in times of a permanent crisis of credibility and the prevailing political, social, and economic agreements.

Impacted by this crisis are also—or especially—institutions devoted to contemporary cultural production: the relevance of such organizations is called into question, the accusation of elitism is repeatedly fielded, and a politics of survey results is increasingly shying away from guaranteeing the resistance a space of independent meaning production. The creative industries are enmeshing cultural production with their tourist spectacles in an attention economy of grand figures. When the cultivation of binding commitment regarding the meaning of contemporary art and culture for the imaginings of our present seems difficult at best, then perhaps it is precisely the “archaeology” (or genealogy) of the present that is assigned increased significance. How could the history of the deculturalization of the present be written? Do archives offer potential for the reconstruction of those “discursive formations”, as Michel Foucault called them in his analyses of power, which result in technology and economy being presented today as prevailing signifiers? So can archives be politicized?

In recent years, a series of artistic positions were present—both in the exhibitions of Camera Austria and in the magazine Camera Austria International—which deal with questions related to the archive. Artists like Özlem Altin, Sven Augustijnen, Eric Baudelaire, Peggy Buth, Martin Beck, Peter Friedl, Maryam Jafri, Stephanie Kiwitt, Tatiana Lecomte, Uriel Orlow, Ines Schaber, Shirana Shahbazi, and Ala Younis, among others, construct in their artwork a kind of archive—temporary, provisional—and compile collections, taking the material found in archives or discoveries that lead to archives as a point of departure for their research. So on the one hand, the point is to imagine archives that do not exist but would be necessary, and on the other, to add something to archives that is lacking, that is repressed or excluded. Here, artistic practices also intervene in knowledge production in a more general way; they institute, as it were, methods of producing knowledge that is missing, and at times assume the functions of other cultural institutions in the process.

Our surveying of the Camera Austria archive attempts to bring together these different explorative questions. Is it a (previously unpublished and non-public and thus) missing archive that could add something not yet present to the established narratives on the relevance of contemporary art, or, more precisely, contemporary art photography? How can those “sites” within the archive be located, according to Peggy Buth, where the act of making visible the un-visible of the archive would need to start? How could it be brought into association with the erratic reconstruction of history by Eric Baudelaire or the idea of the “anti-archive” by Peter Friedl? And how about the uncomfortable question of what power this archive may hold? Has this archive also produced something like an Other? So which practices could help discover the critical points that are capable of making visible an “unease about history” (Georges Didi-Huberman)? Which history is even actually being conveyed in and through this archive? And which other histories could it—also—tell?

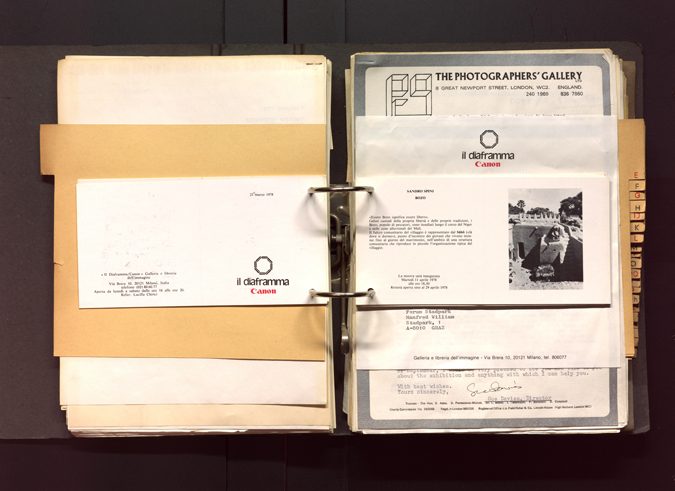

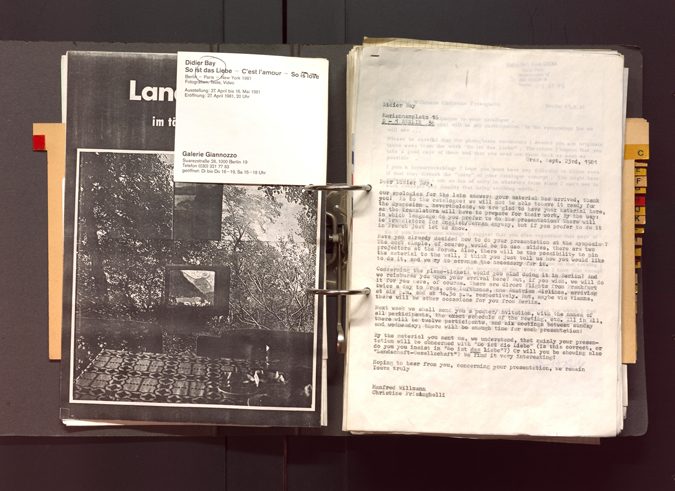

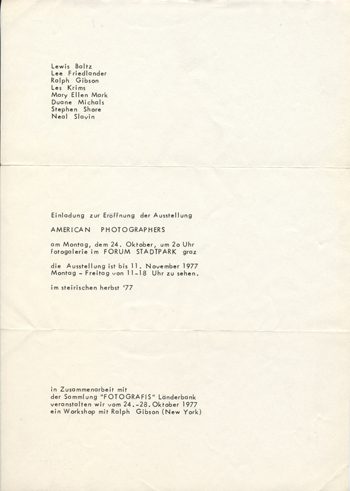

A special issue of Camera Austria International, which will be published in June 2017, is a first step towards publishing the archive. The material in this issue originates from the years between 1974 and 1983: the first exhibition activity at Schillerhof in Graz, the move to Forum Stadtpark in 1975, the implementation of the first symposia on photography starting in 1979, the publication of the magazine Camera Austria – Zeitschrift für Fotografie as of 1980, the publication of the first books starting in 1982, and also a phase of—precarious—project consolidation.

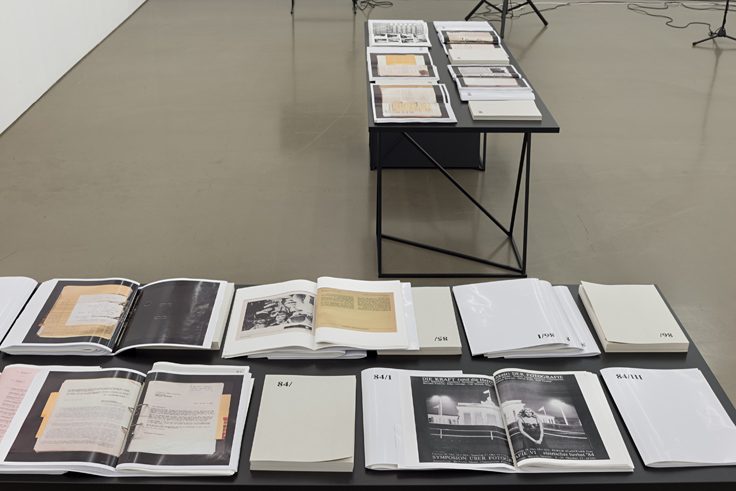

In parallel to this issue of the magazine, we have been preparing the current exhibition project since early 2015, which will be presenting the archive from the years 1974 to 1989. The artists Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch have developed a publication concept in which all archival material is shown in a series of facsimiles connected as various folders, basically as a reference at hand. This will be accompanied by video footage of the symposia on photography the years in question. During the second part of this exhibition project, from December 2017, material from the years 1990 to 2002 will be shown, before Camera Austria moved into the present space in the Eisernes Haus in 2003. In the context of this exhibition, the exhibition spaces of Camera Austria will also be restructured: the wall separating the library from the exhibition space will be dismantled, allowing the entire space to be converted back to the original state as designed by architects Peter Cook and Colin Fournier. The opening up of the library space aims to imbue the counterpart so inextricably connected to the images with enhanced presence: text.

The publishing of artists’ books and the books accompanying our exhibitions has once again taken on greater importance since 2014 in the form of a new publication series on contemporary photography. Mobile bookshelves—also designed by Six and Petritsch—lay claim to space within the exhibition paradigm to which nearly all museums and institutions have become subject during the last twenty years, at the expense of research activity and care of the collections. With this exhibition, the archive as a whole—a collection of highly diverse texts and images—is reconquering the exhibition space. Yet it does not become an exhibition showpiece in the process, but rather retains its heterogeneous form as “discursive formation”: as the result of a collective network of protagonists that has continually opened up spaces of meaning by working with images, continually redefining these spaces and continually rewriting the meaning of the images. Working with images as a space of interpretation.

From the start, we decided to not make a selection, but rather to publish the archive in its entirety—the compendium of materials will be available in our library after the exhibitions are over and thus remain accessible. It signifies the point of departure for further research—the archive departs from the file cabinet and reverts to a not-yet-fully-defined form in order to expose itself to the issue of its “truth production”.

At any rate, the concept of the archive appears to permit—beyond the viewing, classifying, and interpreting of material—a kind of stratagem, thus moving beyond the continuity of the history of a specific institution—having devoted itself to working with photographic images, even if only hypothetically—that requires re-narrating or re-enacting, taking a detached view. It seems necessary to introduce a discontinuity into a history of this work with images, which, for its part, is marked by its own discontinuities, as can fully be assumed, and by an enmeshment of theory and image, text and image. “A one-dimensional concept of reality, a linear conception of history, in principle leads to a one-dimensional substitute: I document, therefore I am—therefore I am historical” (Albert Goldstein).

Just as the questions that have been directed at photography since the 1970s can hardly be understood as a development—not even of discontinuous nature—neither can the work with images itself be considered a development. In contrast, imagining this long-standing period of institutional, artistic, and theoretical production as a dispersed, non-context-bound archive compels us to refrain from pursuing a reconstruction, and instead to seek updates and restructuring rather than conveniently becoming immersed in and perpetuating continuity.

Therefore, the concept of the archive possibly allows for certain distance to be assumed before we once again approximate the texts, publications, magazines, invitations, press texts, manuscripts, and so forth, in order to consider whether they reference our current practice or not, and also how the differences, the distance, might be indicated. Does this archive and its language, its ways of representing, even reference the same kind of documents that we would today identify as the focus of the archive, namely, photographic images? Do we mean the same thing today when we speak of photographic images and their capacity to show, to represent, to document, to construct a system for describing our respective presents, to intervene in our life?

Ultimately, the idea of the archive also necessarily involves the idea of incompleteness; an archive is incomplete, displaying discontinuities, gaps, never being fully subject to a logic of order, always remaining never-ending and even at times emerging by chance. Is it also subject to an “aleatory materialism”, as Nicolas Bourriaud applies to history (including the history of art)? And each archive provokes the question of what cannot be found there, what has been caused to disappear. So does this imply that the archive, like photography itself, is permeated by zones of visibility and zones of invisibility? How can that which is not visible be seen? The archive as a stratagem for reflection thus helps us to understand that it does not remind us of history, nor does it enable us to reconstruct this history, but it might indicate what this history is capable of reminding us of, what the archive is able to disclose. Perhaps this memory will deliver to us arguments for counteracting the increasing marginalization of knowledge, which denies, ignores, and suppresses this history.

The production of a concept is a provocation, a refusal to answer to the call of the known and an opportunity to intensify our experiences. The archive is therefore not representational, it is creative, and the naming of something as an archive is not the end, but the beginning of a debate.

Pad.ma