To What End?

Infos

Opening: 26.9.2015, 5 pm

Duration: 27.9.–22.11.2015

Opening hours:

Tue–Sun 10 am–7 pm

Artists:

Heba Y. Amin (EG)

Takashi Arai (JP)

Mohamed Bourouissa (DZ/FR)

Hrair Sarkissian (SY)

Vangelis Vlahos (GR)

Curated by

Gülsen Bal (GB/TR) &

Walter Seidl (AT)

Co-produced by steirischer herbst 2015

Intro

The exhibition “To What End?” raises questions about future models of existence by looking at countries that have undergone moments of crisis in political, social, and economic terms driven by every possible force of intervention (Egypt, Greece, Japan, Nagorno Karabakh Republic, the United States). Exploring new ways of thinking about the agency of subjects with a particular focus on the ever-changing understanding of cultural paradigms, the represented artists assess the possibilities of a post-national sense of belonging in both its local and global formulations. In search of the relevance of the past and its effects on today, the exhibition focuses on specific moments in recent history that have brought about changes on a global scale lingering in the present realm of political debate (for instance the economic crisis in Greece, the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, or the revolution in Egypt).

This leads us to the point where the exhibition “To What End?” grasps and measures the ruptures of various cultural-specific “heritages” resulting from different conflicting forces of power. The exhibition negotiates historically arising consciousness vis-à-vis the menacing political and economic effects that accompany diversified experiences of the self. At the same time, it probes the issue of what cultural “heritage” means in circumstances of variable forms of singularity that foster the marginalisation of social and national contexts.

To What End?

The exhibition “To What End?” raises questions about future models of existence by looking at countries that have undergone moments of crisis in political, social, and economic terms driven by every possible force of intervention (Egypt, Greece, Japan, Nagorno Karabakh Republic, the United States). Exploring new ways of thinking about the agency of subjects with a particular focus on the ever-changing understanding of cultural paradigms, the represented artists assess the possibilities of a post-national sense of belonging in both its local and global formulations. In search of the relevance of the past and its effects on today, the exhibition focuses on specific moments in recent history that have brought about changes on a global scale lingering in the present realm of political debate (for instance the economic crisis in Greece, the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, or the revolution in Egypt).

This leads us to the point where the exhibition “To What End?” grasps and measures the ruptures of various cultural-specific “heritages” resulting from different conflicting forces of power. The exhibition negotiates historically arising consciousness vis-à-vis the menacing political and economic effects that accompany diversified experiences of the self. At the same time, it probes the issue of what cultural “heritage” means in circumstances of variable forms of singularity that foster the marginalisation of social and national contexts.

“To What End?” engages in notions of “heritage” as a device for relinking and reclaiming historical memory and remembrance in an effort to bring in a critique of dominant narratives and cultural assumptions. These notions reflect distinct stages of lived experience, addressing personalised histories through a variety of visual regimes by looking into the eyes of another or with the eyes of an °“Other”. The artists tackle the question of how to understand the meaning of “heritage” when it comes to offering multiple voices that refer to different cultural and sometimes oppressed contexts. Being mostly associated with generative forces towards living, the artists look at common models of interaction in order to formulate a radical break through their works. As a result, critical voices about the past, present, and future evolve by means of redefining structural boundaries, progressing towards claiming if not situating political subjects in a certain way, which provides a look at the intersection of ever-increasing social, political, and economic codes of interaction of “universal” nature.

Irrespective of the ambiguity of other problematics, the exhibition “To What End?” advances critical statements about past and present that have the potential to open up new territories of thought vis-à-vis current identity formations in the explorations of how individual subjects can assert themselves from a present-day perspective. Instead of only looking at their own countries (of origin), some of the artists shift attention to different locales and to how historically arising conflicts have shaped a present cartography of identity mapping. Then, how does the use of images influence our perspective on identity that is supposedly bereft of any national positioning but has become the focus of a global mapping of political terrains?

At stake are the changing parameters of the transnational questions of belonging that necessitate a sense for global shifts of power. While micro-territories often give rise to universal forms of conflict, there are multiple elements that conduct political interventions permeating the notion of “statehood” or of individual power.

The works shown in the exhibition question every space as a site for intervention and interruption by revealing the rapid transformation processes at several turning points in history. These interventions have not always come from the outside but are often necessitated by internal struggles in order to assert the power of self-enunciation and self-emancipation. The camera as a medium helps to record such events and situations that create a multiplicity of visual connotations. Thus, the artists in the exhibition hint at very specific moments in contemporary history, which call for an understanding of current modes of transformation in order to challenge visual paradigms and media channels as a set for predetermined forms of argumentation.

Taking various examples of conflict zones around the world into consideration, which cannot be broken down into only one single problem, “To What End?” explores the conditions that advance and influence forms of resistance towards a new positioning of the self in the wake of the political demands imposed by a post-national, neo-liberal economy. The exhibition destabilises the former centre–periphery debate by looking at different sociopolitical and economic territories where conflicts evolve out of a microcosm of deregulated power formations. In such “contested” zones, individuals are forced to reclaim their territory, which throws in questions about global attempts at levelling economic and political standards. War-torn enclaves are only one example of how the fight over territory is based on habitual resources and political influence. The general question relates to how to put an end to conflicts arising from various reasoning—conflicts that cannot always be controlled but need to be resolved in order to help cultural multiplicity redeem its mandate.

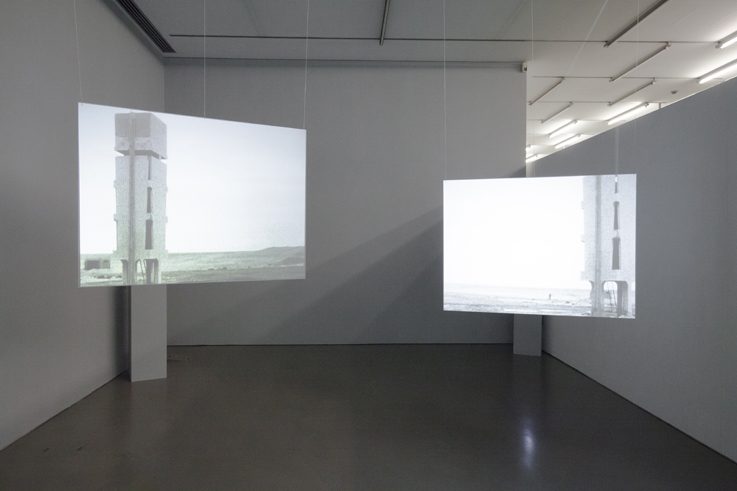

Heba Y. Amin

“Project Speak2Tweet” (2011)

On 27 January 2011, Egyptian authorities succeeded in shutting down the country’s international Internet access points in response to the growing protests in public. Over one weekend, a group of programmers developed a platform called “Speak2Tweet” that would allow Egyptians to post their breaking news on Twitter by using voicemail messages despite Internet cuts. The result was thousands of heartfelt messages from Egyptians recording their emotions by phone. A few years later, the revolution is still ongoing, but the messages are no longer accessible to the public. Heba Y. Amin collected these messages and created an archive of textual and phonetic documents reporting on the heritage of the Mubarak regime and the questions that many posed about what the end of this regime would look like. Hence, “Speak2Tweet” composes a unique archive of the collective psyche; with voices disappearing into the depths of cyberspace, this project has brought forth the unique narratives and, in turn, connected them once again to the physical realm. Project Speak2Tweet is both a research project and a growing archive of experimental films that utilises “Speak2Tweet” messages sent prior to the fall of the Mubarak regime on 11 February 2011, juxtaposing them with the abandoned structures that represent the long-lasting effects of a corrupt dictatorship. The project interrogates the reimagining of the urban myth, of visualising the city from the “personal” perspective through the highly problematic constructs of (un)democratic tools. It explores the emergence of the imagined city from internal monologues and investigates historical narratives by means of glitches in digital memory. Through the multilayered spatial relationships, the project attempts to portray the psychology of the urban realm. As the visual archive grows, “Project Speak2Tweet” changes into a constantly altered space that creates a delusion of the inner voice. Photographs of abandoned buildings are paralleled with the messages abandoned from the public; together, they denote the ghost structure of a former political reality that changed the view on the past and present of the Egyptian state.

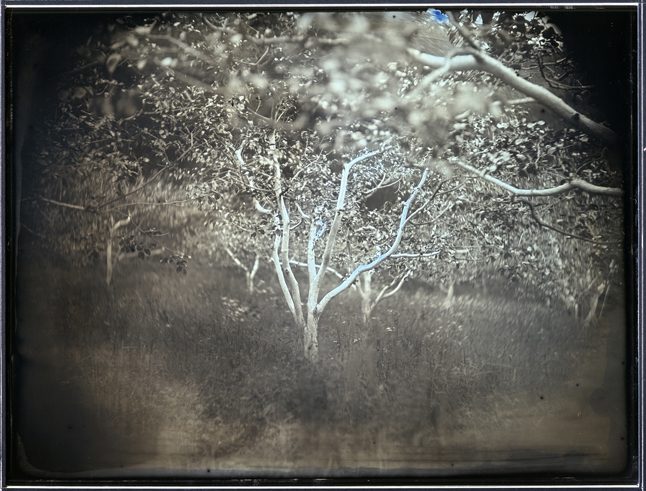

Takashi Arai

“Here and There” (2011–12)

Of the many photographers documenting the effects of the tsunami and the reactor explosion of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant on 11 March 2011, Takashi Arai takes a special stance in his way of portraying the radioactively polluted landscape and its inhabitants. Instead of using conventional photographic techniques of the current digital age, Arai goes back to one of the first techniques to enable photographic representation in the nineteenth century: the daguerreotype. Looking at a daguerreotype gives rise to a different sensation than looking at any other photograph. A sheet of silver-plated copper is polished to a mirror finish and then treated with fumes to make the surface light sensitive for exposure in a camera. The final image does not sit on the surface of the metal carrier but appears to be floating in space while protected by glass. Hence, the depicted subjects and objects sometimes have an eerie gestalt, which also relates to Arai’s daguerreotypes from the Fukushima area. A haunted landscape appears in front of the camera, where trees and branches seem to be glowing in the sunlight, for instance those of a persimmon tree. Night-time fumes seem to ascend in front of a Family Mart grocery store, which stands alone in the darkened landscape but is open 24/7. With the daguerreotype process, Arai visualises the potentiality of radioactive waste and equally conveys a mesmerising pictorial scenario oscillating between reality and fiction. Workers and inhabitants of the area happily pose in front of the camera as if there had been no incident at all. With this special photographic technique, which was officially released in 1839, beholders also get the impression of travelling back in time, for instance to an old fisherman’s village built out of wooden shacks. Thus the artist hints at the dialectics between past and present, which is also mirrored in the title “Here and There”. Moreover, questions about the past and its influence on the present without a predictable outcome are raised while contemplating the images in a technically set-up, darkened exhibition context.

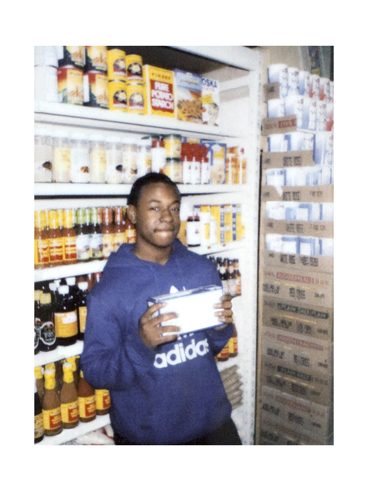

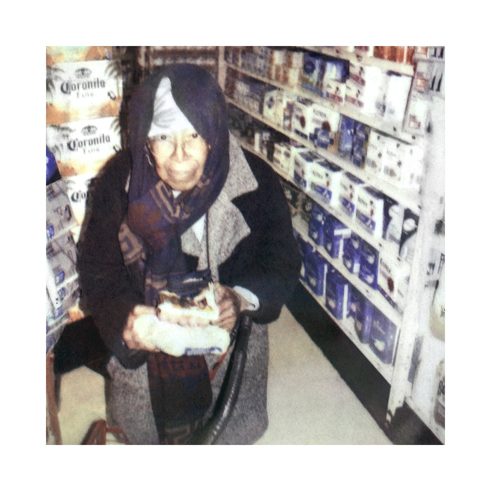

Mohamed Bourouissa

“Shoplifters” (2014–15)

The series “Shoplifters” by Mohamed Bourouissa consists of retouched photographs of Polaroid snapshots that were taken in New York grocery stores. The photographs depict people who were caught by the stores’ security guards while trying to steal items off the shelves. In the pictures, beholders see the respective people smiling into the camera and demonstrating the goods they were about to steal. Later, these snapshots were mounted on a board at the entrance or exit of the stores in order to identify the people on the occasion of another visit. The boards relate to a cartography of petty crime that identifies the protagonists in an analogue, direct manner similar to a police file. This approach to photographic representation as a means of immediate identification in public space, however, was later forbidden as a viable practice. Bourouissa’s work hints at the downfall of capitalism and the increasing inaccessibility of common goods to many. Since the 1990s, New York’s gentrification processes have driven many out of the centre into more affordable neighbourhoods such as Brooklyn, which is also the site of Bourouissa’s observations. Even this borough has undergone dramatic changes in recent years, which, for many inhabitants, has caused a struggle for survival on a daily basis. Although the majority of the depicted people in the photographs are African-Americans, the reality of living in one of the most capitalist cities of the world forces many to look for alternatives in order to cope with the growing financial demands raised by housing and living. What will the demographic changes look like in the years to come, once Manhattan has lost the alternative appeal it used to have, especially for artists, and finally become a haven only for financial tycoons unaffected by any monetary crisis? The photographs of the “Shoplifters” series in the exhibition setting raise questions about the complicity alluded to in the protagonists’ poses. While New York tries to keep its stronghold as a financial capital, many micro-territories and social segments have been subject to change, to which the social use of images testifies as a document for reinterpreting reality.

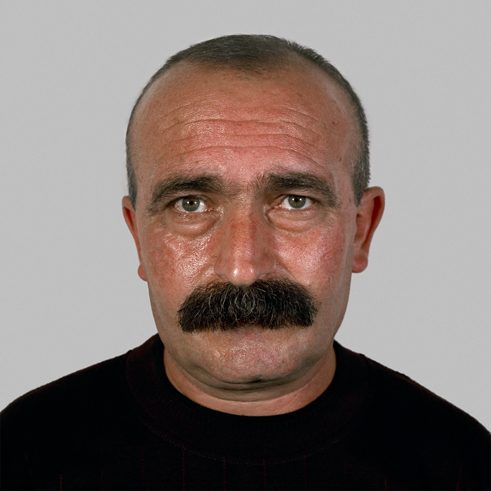

Hrair Sarkissian

“Front Line” (2007/15)

Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian’s work often deals with the artist’s personal background relating to the Armenian diaspora. His work °“Front Line” was originally conceived in 2007 but shown for the first time in 2015, a century after the Armenian genocide carried out by Turkish forces during and after World War I. Like so often, the artist shifts attention away from the actual Armenian territory, and in this case he focuses on the war-torn enclave between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the self-proclaimed Nagorno Karabakh Republic that fought a war for independence between 1988 and 1994. The Armenian population’s wish to reunite the territory with Armenia remained unfulfilled, yet Azerbaijan opted for a ceasefire and recognised the existence of Nagorno Karabakh in 1994. Since the end of the war, the governments of Armenia and Azerbaijan have been holding peace talks on the region’s disputed status, where an economic blockade resulted in a confrontation between Turkish-backed Azerbaijan and Russian-backed Armenian forces. Today, over a million Azeri and Armenian inhabitants remain displaced, and Western powers are still trying to negotiate a long-term solution over a territory that continuously faces political unrest. Sarkissian’s photographs portray both the tranquillity of the landscape and the Armenian “freedom fighters” who were involved in the liberation movement during the war. Their portraits are shown in three-dimensional glass cube structures on an array of plinths, reinforcing the protagonists’ unified willingness to fight for independence due to their ethnic and national displacement. Large-scale wallpaper depicts the landscape in the back to visualise the territory they have been fighting for. The setting denotes the estranged environment in which the protagonists saw themselves when fighting for recognition. Being isolated in a territory that had no clearly defined status relates to struggles with predefined notions of heritage and the dissolution of historically determined cultural values.

Vangelis Vlahos

“The Bridge” (2013–15)

Vangelis Vlahos’s artwork deals with found photographic and textual material and engages in reworking historically documented facts in order to create new, decentred narratives within recent history. “The Bridge” is one of Vlahos’s latest projects, referring to a trade agreement between Greece and Syria during the 1970s and 1980s. This commercial agreement was set up to establish a direct truck-ferry service between the Greek port of Volos and the Syrian port of Tartus. This ferry service was part of a broader trade route connecting Europe to the Middle East and the Arab world. At the time, the particular route was considered the most important and easy way to transport commercial goods. The ferry link between Volos and Tartus, operative from 1977 until 1988, was eventually discontinued because of the unstable political situation in the Middle East already looming in the 1980s. Researching the history and narratives behind this ferry service, Vlahos operates with found photographs of the time in order to recreate and reimagine a trip between the two ports. The order of the images, placed next to each other on top of a fifteen-meter shelf, follows loosely the original route of the ferry, starting from Volos and ending in Tartus. With this project, Vlahos links current political problems in both countries to contemporary history and the conflicts in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and the Middle East which have been brewing for decades. “The Bridge” sets out to associate historical consciousness with an awareness for national and political changes that have been brought about by recent moments of crisis. How does the reversal of historically made decisions and actions transcend the present? How have culturally inherited bonds ceased to exist and how can historical failure reactivate such relationships in the future? Some of these questions are asked while delving into an immediate past when the signs of an upcoming future were not yet visible but lingering in national and political agendas.