Press information

Platform Wars

Infos

Press preview

13.3.2026, 11 a.m.

Opening

13.3.2026, 6 p.m.

Duration

14.3. – 17.5.2026

With works by

S()fia Braga, Joshua Citarella, Ganslmeier & Zibelnik, Zarina Nares, Frida Orupabo

Curated by

Mona Schubert

Press downloads

Press Information

In the fall of 2025, Donald Trump hosted a dinner for the CEOs of leading tech companies. Counting among the guests were the heads of Meta, OpenAI (developer of ChatGPT), and Alphabet (Google’s parent company). Notably absent was one of Trump’s former confidants, Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla, SpaceX, and X. In early 2025, Musk was still serving as one of the US president’s advisors, yet their falling out was not long in coming. The dinner event, attended by thirteen billionaires and numerous other guests with fortunes in the millions, was one of the most affluent gatherings in the history of the White House.¹

It marks a surprising turn in Trump’s historically tense relationship with the tech and AI industry. After years of public attacks and even the 2022 founding of his own online platform, Truth Social, Trump was now aiming to stand shoulder to shoulder with those very corporations he had once sharply criticized due to their market power. For these Big Tech companies, proximity to the US government could only mean one thing: influence. In an increasingly contested global technology landscape, political cooperation has become a site-related advantage—even if at the expense of previously propagated ethical values. Since Trump’s election victory in 2024, the US technology sector has cozied up to Republican thinking more and more, while clearly starting to leave initiatives promoting diversity and equality in the dust.

This interest in moving closer to such conservative values harks back to an extended process of development: a decade of skepticism followed the initial platform optimism so characteristic of the mid-decade after the turn of the millennium, where social media promised participatory engagement and thus a democratization of digital spaces.² Such skepticism arose through factors like the dissemination of fake news, the mobilization of extremism, and the targeted spreading of disinformation, along with the resulting court cases³—thus confronting the “tech lords”4 with the negative ramifications of the tools they had spawned. In the early 2020s, major economic restructuring ensued, for instance through the founding of umbrella companies: in 2021, Facebook was integrated into the global infrastructure of Meta through a rebranding campaign. Just a year later, Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter—an extensively used mouthpiece that was particularly popular with journalists—and the platform’s renaming as X underscored the fragility of the protection measures already in place. At the same time, a geopolitical consciousness was on the rise: TikTok, the successful app for short videos by the Chinese tech company Bytedance, which was the first big social media platform outside the United States, was effectively banned within the US in early 2025. The official reason given was national security. This occurrence makes it clear that such platforms have long since become a playing field for national interests.

Making reference to these developments, the group exhibition Platform Wars explores how centralized online platforms—Instagram, Facebook, X, and TikTok—have developed from channels for exchanging texts or images into powerful political and economic infrastructures. In no way are these platforms neutral places for saving user-generated content, for they in fact exert enormous influence on our everyday lives through algorithmic curation, invisible moderation systems, and user guidelines. These platforms’ inner workings influence not only cultural production, but also the social dynamics of visibility, the formation of identity, and the shaping of political opinions.

The title of the exhibition references the currently running blog series “The Platform Wars” (2023–ongoing) by Joshua Citarella, an artist and the podcast moderator of “Doomscroll.” In this series, he explores the transformation of platform cultures and online subcultures, posing speculative questions about how these infrastructures can be negotiated, altered for different purposes, or subverted.5 Against this backdrop, the exhibition Platform Wars presents five international artistic positions that investigate how capitalist imperatives determine the digital attention economy, how hierarchical systems spread within online communities, and how postdigital aesthetics change visual culture. Here, “platforms” are not seen as purely technological spaces, but as sociopolitical venues where commercial imperatives, ideological agendas, and user interests clash. The selected artistic positions, rather than detailing technological developments, formulate critical theories about how image politics unfurl on the Internet.

In users’ everyday life, platform logic becomes especially evident in situations where it serves as a basis for earning income. S()fia Braga examines, in her installation Platform Workshippers (2023–25), the interplay between online identity, self-marketing, and digital labor. Aided by a compass diagram, the artist charts different user archetypes—including daily vloggers, NPC streamers, and WIII GRWM creators—and then connects them to the tree of life as a mythological-religious symbol. Thus arises a cosmology of the postdigital world. The title of the piece is a play on words: “worshipper” connects the term “work” (labor) with “worship” (ritual). The neologism pays reference to the ritualist dimension of platform work: users operate as workers and as believers at the very same time. Rather than being mere places of entertainment or escape, feeds and livestreams become tools for generating personal income and also engines of perpetual value creation for platforms.

While Braga probes the ritualized dynamics of postdigital work, Joshua Citarella focuses on the ideological gestures of self-localization within platform-based public spheres. His series e-deologies (2020–25) compiles flags found online, usually designed by teenagers and melding different political ideologies. Here, for example, we might encounter peculiar and quite contradictory combinations such as “anarcho-primitivist caliphate,” which links the rejection of modern civilization (anarcho-primitivism) with the authoritarian power structure of a system of rule legitimized by Islam (caliphate). These flags are often produced inexpensively using print-on-demand services and then hung on the walls of the rooms of children and teenagers—similar to the way the two previous generations, namely, Generation X and Millennials, hung up posters of their favorite bands. Such hyperspecific categories enable Gen Z to position themselves within an increasingly chaotic online political landscape.

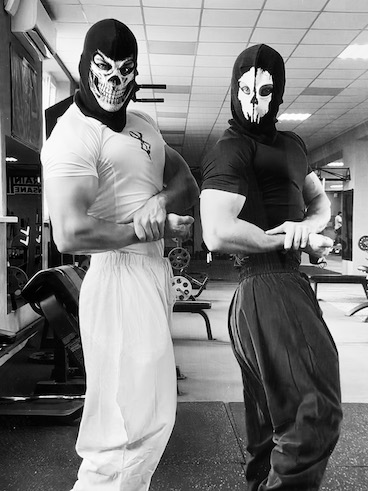

Just how quickly such playful forms of political self-localization can spin off kilter into radicalized conceptions of the world is aptly demonstrated in the work of Jakob Ganslmeier & Ana Zibelnik. In their multimedia installation Bereitschaft (Readiness, 2024–25), the artist duo brings visibility to the ideological undercurrents rooted in so-called GymBro fitness communities and extreme practices of self-optimization like “looksmaxxing,” “bonesmashing,” and “mewing.” Such behavioral tendencies have long since become mainstream, seen especially in video-based social media apps like TikTok, after having been previously confined mostly to subcultural, divisive forum websites like 4chan and Reddit. Today, such tendencies are not mere niche aesthetics; they are also associated with the rise of right-wing populism in the Global North.6 Ganslmeier & Zibelnik’s installation takes a look at the structural dynamics of social media, where algorithmic amplification favors user engagement over critical media literacy and prompts the spread of extremist ideologies and radicalization.

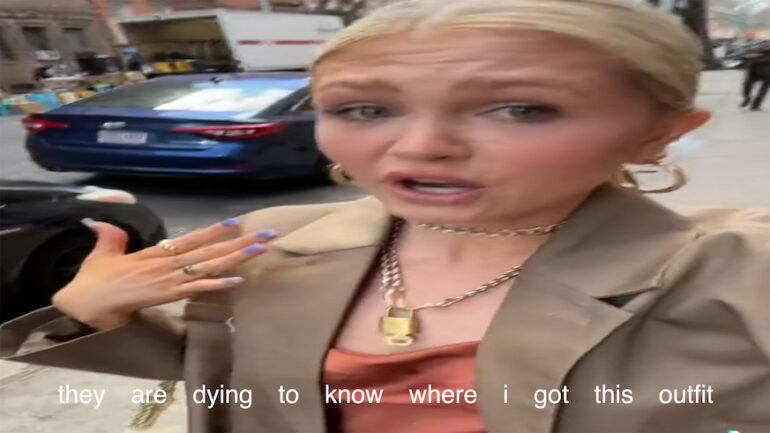

Ganslmeier & Zibelnik shed light on the nexus of platform logic, toxic masculinity, and dynamics of radicalization, while Zarina Nares delves into the question of how an understanding of femininity is shaped on social platforms and is also performatively staged to garner clicks, attention, and consumption. In order to reveal these mechanisms, Nares appropriates popular content formats in her video work Meditation For Releasing The Capitalist Patriarchy Within (2022), for instance hauls, vlogs, or self-optimization videos, and deliberately exaggerates them. Attractiveness and desirability become a capital worth coveting in order to capture the male gaze and attend to commercial interests. Especially for young women, who seek orientation in these digital spaces, such imagery comes to represent a promise of social recognition, with the pictures serving as normative templates for shaping self-perception, consumer behavior, and self-esteem.7

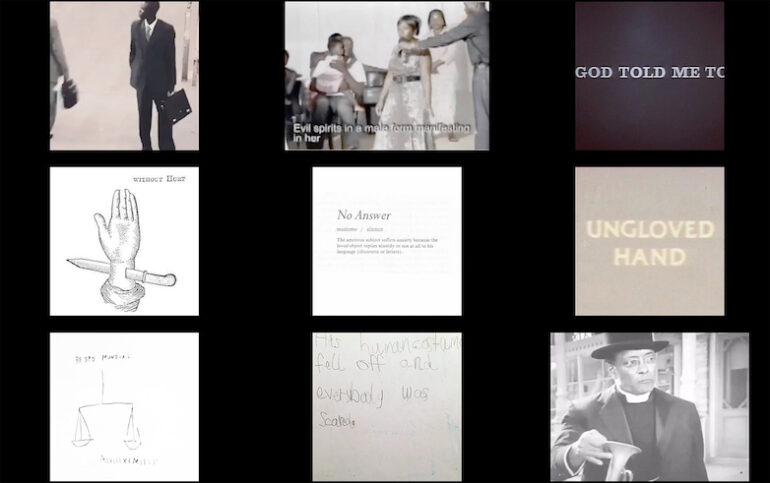

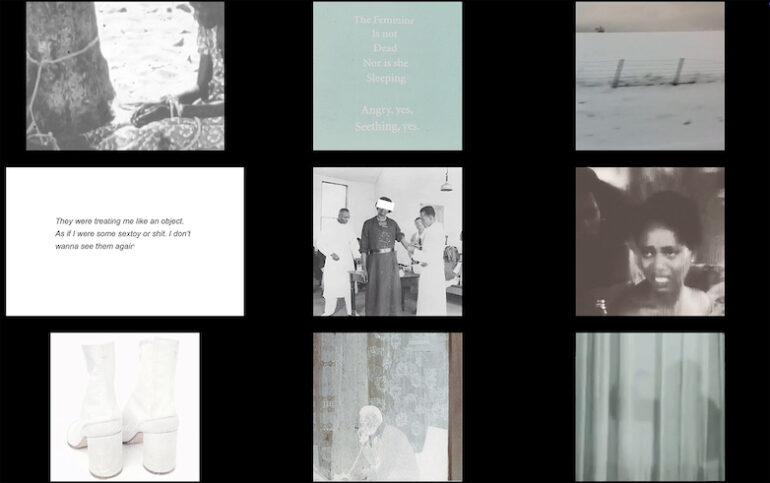

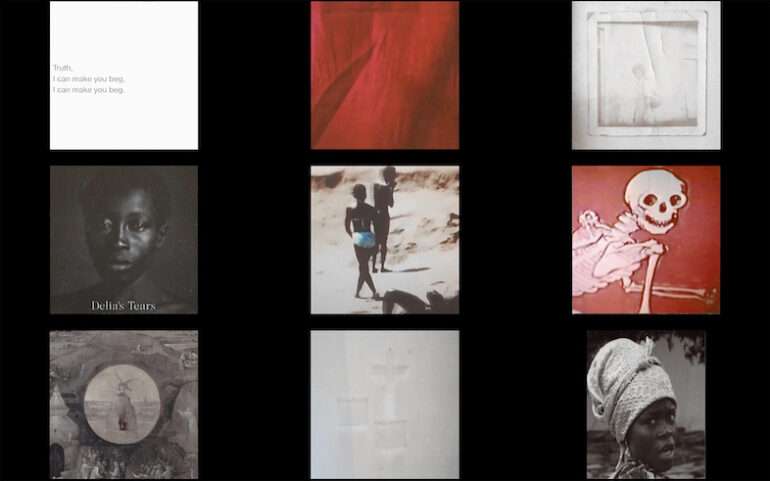

Frida Orupabo, in turn, shows how artistic resistance can take place directly on the platforms themselves. Her video installation Untitled (2018) goes back to her Instagram account @nemiepeba, where she, as a sociologist and autodidactic artist, first stepped into the public sphere with her work. Although nowadays most artists use their social media feeds as a means of promoting their artistic work,8 in the case of Orupabo her feed is a visual tool for making structural injustice visible. The artist extracts renderings of Black female bodies from historical photographs and ethnographic, medical, and scientific sources, as well as art and pop culture, in order to spotlight colonialism, racism, and sexism. Curating these fragments drawn from the everyday pool of media engenders an eclectic assemblage that bears witness but also sparks bewilderment. In 2021, Tina M. Campt described this approach, which is likewise mirrored in the artwork of Deana Lawson and Arthur Jafa, as follows: “What defines and unites their divergent practices is their ability to make audiences work. They refuse to create spectators, as it is neither easy nor indeed possible to passively consume their art. Their work requires labor—the labor of discomfort, feeling, positioning, and repositioning—and solicits visceral responses to the visualization of Black precarity.”9 In that sense, Orupabo uses Instagram not only as an archive, but also as a performative instrument, she is undermining the logic of whirlwind image circulation and compulsive media consumption. It becomes clear how deeply anchored racial discrimination along with colonial and gender-specific violence still remains in contemporary—and especially networked—visual cultures.

The works presented in the exhibition, all of which originate between 2018 and 2025, reflect an inventory of the dynamics of centralized social media platforms—ranging from the ritualized logic of labor to ideological self-positioning and gender staging to racist structures. However, these positions are not only shaped by cultural and economic considerations, but rather, as mentioned above, are also increasingly entangled in geopolitical power interests.

Artificial intelligence will serve to intensify the range, speed, and complexity of these mechanisms. In fact, 2026 might be the first year where image content is so strongly influenced or generated by AI that we are hardly able to tell what is “real” and “true”10 anymore. If the boundaries between reality and fiction keep blurring more and more, then bias, radicalization, and algorithmically controlled propaganda could become even more potent. Intervening in these processes will be the next big task of cultural and educational institutions—and it is precisely here that artistic works can make a vital contribution: they make it possible to gather mechanisms, structures, and tensions from such platforms and to translate this information into a critical form that is tangible to our senses.

1 Dave Smith, “Meet all 33 Silicon Valley power players at Trump’s high-profile tech dinner—and here’s Elon Musk’s explanation for why he wasn’t there,” Fortune, September 5, 2025, https://fortune.com/2025/09/05/trump-tech-dinner-full-attendee-list/.

2 Joshua Citarella and Jakob Hurwitz-Goodman, On Platforms, from the series When Guys Turn 20, dis.art, 2023, https://dis.art/on-platforms.

3 This is reminiscent of several developments: the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal in 2018, which exposed the political use of grossly exploited user data; the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, an event in which social networks, especially Twitter (today, X), played a pivotal role by helping to radicalize and mobilize those involved; and the proceedings initiated in 2025 by the European Commission against Meta (owner of platforms like Instagram and Facebook) based on the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) due to insufficient measures against disinformation and a lack of transparency.

4 See Jodi Dean, “The Neofeudalising Tendency of Communicative Capitalism,” tripleC 22, no. 2 (2025), pp. 197–207, and also Jodi Dean, Capital’s Grave: Neofeudalism and the New Class Struggle (New York: Verso Books, 2025).

5 See various contributions by Joshua Citarella: “The Platform Wars,” Substack, May 10, 2023, https://joshuacitarella.substack.com/p/the-platform-wars; “Platform Wars (part 2): Twitter & the Blue Check,” Substack, June 7, 2023, https://joshuacitarella.substack.com/p/platform-wars-part-2-twitter-and; “Platform Wars (part 3): TikTok & Geopolitics,” Substack, August 9, 2023, https://joshuacitarella.substack.com/p/platform-wars-part-3-tiktok-and-geopolitics; and “Platform Wars (part 4): A Public Option for Social Media,” Substack, October 11, 2023, https://joshuacitarella.substack.com/p/platform-wars-part-4-a-public-option. On this topic, see also Mike Pepi, Against Platforms: Surviving Digital Utopia (New York and London: Melville House, 2025).

6 See also Angela Nagle, Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right (Winchester: Zero Books, 2017). Inke Arns and HMKV, eds., Der Alt-Right-Komplex: Über Rechtspopulismus im Netz, exhibition magazine by HMKV, no. 1 (2019).

7 See also Sophie Publig and Charlotte Reuß, “Becoming-Girl: On Posthuman Subjectivities and Algorithmic Epistemologies,” artist talk, Aksioma, Ljubljana, May 13, 2025, https://aksioma.org/ayasu/artist-talks/becoming-girl/.

8 See Annekathrin Kohout and Wolfgang Ullrich, eds., “art meets social media: Schöne neue Kunstwelt,” Kunstforum 305 (2025), pp. 48–59. This also calls to mind the practices of self-staging by Amalia Ulman (Excellences & Perfections, 2015) and Andy Kassier (Success Is Just a Smile Away, 2013–ongoing) which started being performatively carried out through fictional influencer accounts in the 2010s (and have continued in the years since).

9 Tina M. Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021), p. 17 (emphasis in the original). On this, also see “Tina Campt on A Black Gaze and Frida Orupabo,” conversation with Owen Martin, Astrup Fearnley Museet, YouTube, May 9, 2025, https://youtu.be/iCSlHONG0So?si=yjSdml6u5hOVhm5w.

10 Anita Chabria, “This is not normal: Why a fake arrest photo from the White House matters,” January 23, 2026, Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2026-01-23/chabria-column-white-house-fake-photo-minneapolis.

Mona Schubert

S()fia Braga (b. 1991) is an Italian transmedia artist and a leading voice in AI-driven cinematic storytelling based in Vienna (AT). Her work explores emerging technologies with a focus on human—non-human collaboration, more-than-human agency, and the power dynamics of centralized social media platforms.

Joshua Citarella (b. 1987) is an artist and writer based in New York City (US). His projects examine internet subcultures, online politics, and meme culture. He hosts the video podcast “Doomscroll,” which investigates digital culture and political discourse in the twenty-first century, and is the founder of the non-profit arts organization “Do Not Research.”

Jakob Ganslmeier & Ana Zibelnik (b. 1990 and 1995) are an artist duo based in The Hague (NL). Their photography and video projects center on youth identity formation, particularly the influence of extremist ideologies on young people. Their practice seeks to dismantle the visual language of radical ideologies and investigates how visual art can counteract radical political narratives.

Zarina Nares (b. 1995) is a New York City-born (US) artist of Indian Muslim and British descent. Working across installation, video, audio, performance, sculpture, and print, she examines how media, digital culture, and inherited power systems shape the psyche, producing tensions between desire and fear, sincerity and performance, empowerment and oppression.

Frida Orupabo (b. 1986) is a Norwegian-Nigerian sociologist and artist living and working in Oslo (NO). Her work consists of digital and physical collages in various forms, which explore questions related to race, family relations, gender, sexuality, violence and identity, with a particular focus on the Black female experience.

Mona Schubert (b. 1991) is an art historian, curator, and writer based in Vienna (AT). Her projects focus on photography at the intersection of art, technology, and media history, photographic exhibitions since the 1960s, and postdigital image cultures. Since 2024, she has been a curator at Foto Arsenal Wien and the festival Foto Wien (AT). In 2025, she completed her PhD at the University of Cologne (DE) on photography at documenta.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.