Press information

Sandra Schäfer

Contaminated Landscapes

Infos

Press preview

10.12.2021, 11 am – with registration only

Opening (cancelled)

10.12.2021, 6 pm

Open as of

14.12.2021

Duration

11.12.2021 – 27.2.2022

Opening hours

Tue – Sun and bank holidays, 10 am – 6 pm

Closed 24.12., 25.12.

1.1.2022 open from 1 pm – 6 pm

Curated by

Reinhard Braun

Exhibition display

ifau – Institut für angewandte Urbanistik

Graphic display

Wolfgang Schwärzler

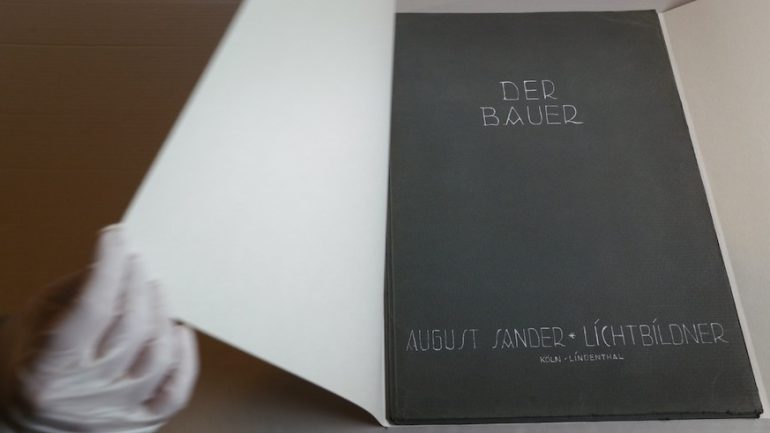

We extend our thanks to the MUSEUM FOLKWANG, ESSEN, and to the Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne, for the August Sander loans.

Press downloads

Press Information

Soon after the German photographer August Sander established his studio in Cologne in 1910, he started traveling to the nearby Westerwald region on a regular basis, taking pictures there for over four decades. The resulting compilation, which includes 2,500 negatives and was originally called a “Peasant Archive,” is today located in the photographic collection of the SK Stiftung Kultur in Cologne, along with Sander’s estate as a whole. The archive encompasses numerous individual and group portraits, but also landscape shots, and it displays many links to the project he started in the 1920s, People of the 20th Century, which ultimately established his importance in the history of photography.

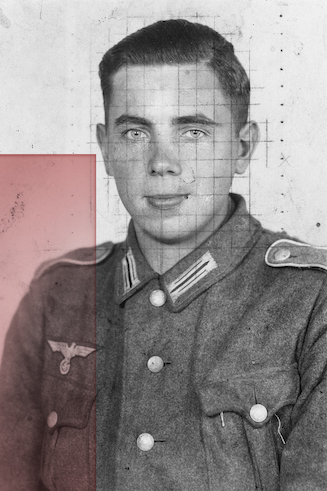

The paths of the family of the artist Sandra Schäfer and those of the famous German photographer cross in this geographic region of Germany—a rural area, shaped by farming culture and mining. In an album belonging to the artist’s great uncle, the name Hilgenroth appears on the back of a photograph; this village is situated in close proximity to Kuchhausen, where Sander resided from 1944 until shortly before his death in 1964.

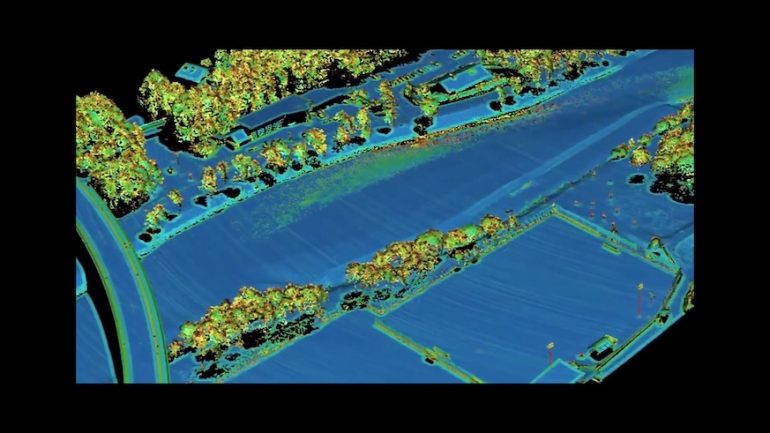

The artist’s family was also photographed by Sander; today these pictures are still privately held. One channel of the video Westerwald – Eine Heimsuchung (Westerwald – A Visitation, 2021) shows Schäfer visiting relatives and neighbors to talk about these photographs, about how they were created and what they meant. Landscapes and forests fill the conversation, but outdoor portraits were also done, yet always with people posing for the camera. Also the landscapes rendered by Sander seem to be shaped by physical labor, by the fields shown. Heimsuchung has more than two meanings here. What still ties the artist to this cultural and social milieu that she had perhaps tried to escape? Didier Eribon writes that “we are so much a product of the order of the social world that we ultimately end up reproducing it ourselves: even as we denounce it or on another level struggle to change it, we validate its legitimacy and function.” So we are haunted by those specters that, as suppressed and repressed memories, secretly lead an undead life, only becoming “visible” as missing images in photo albums. Yet these specters also lead a dual life, as they reflect collectively experienced trauma and a yearning to forget or to change. After the war, everyone was busy trying to survive and wanted to leave the war behind them, as is mentioned in one part of the video. The exhibition Kontaminierte Landschaften (Contaminated Landscapes) projects these gaps and specters to the outside, into the public sphere, which in the Westerwald was and still is primarily experienced as Landschaft (Landscape). Schäfer thus elaborates another form of visibility as well when it comes to these personal and collective gaps and also to the idea of the landscape itself: the second channel of the video shows the monocultural and automated, networked agriculture of the present day, making the album photos of livestock markets, Sander’s landscape shots, and the portraits of “the peasants” seem like something that is nowadays only exploited for tourism advertising.

Everything indeed revolves around questions of representation: Who is doing the showing, what should actually be shown, and how have the contexts of this showing changed? The family portraits taken by August Sander present the families not in a chance constellation on the farm, but rather in their Sunday best. A bourgeois understanding of pictures here always overwrites the rural culture. Photographs of work in the fields or barns hardly exist at all in these images, and even in the later ones the young farmers are seen dressed up for church on Sundays.

It’s important to note that even a photographic endeavor lasting many years and considered to be of a documentary nature, like that of August Sander in the Westerwald, does not actually deliver pictures of this reality. Instead, it subjects them to an already existing visual regime. In the 1920s, Walter Benjamin pointed out this circumstance with highly critical words: “It [New Objectivity] becomes ever more nuancé, ever more modern; and the result is that it can no longer record a tenement block or a refuse heap without transfiguring it. Needless to say, photography is unable to convey anything about a power station or a cable factory other than, ‘What a beautiful world!’ . . . For it has succeeded in transforming even abject poverty—by apprehending it in a fashionably perfected manner—into an object of enjoyment.”

Yet even the family albums do not necessarily prove to be a “counter-archive” to this kind of aesthetic enjoyment that translates social reality into the pictorial form of a photograph, or overwrites it in this way. There, too, day-to-day life is hardly present. People want to be remembered through portraits. City and landscape views from travels are found in the albums, usually devoid of people; the first drive on the autobahn has been documented. There are many group portraits taken on special occasions, at family celebrations, church days, or community festivities. Uniforms and swastikas appear and disappear again. The only pictures that might be called snapshots are found in an initially destroyed album belonging to the artist’s grandfather. It documents a homecoming celebration for soldiers, featuring photos taken by Herbert Ahrens in May 1943 showing crowds of people. The pictures in the other albums are oddly arranged, the way it is in our own family albums. So the specters have not actually disappeared from these archives—quite the contrary. Perhaps they are the very ones to force these acts of staging and to hamper change, all the while seeming to provide social stability.

Sandra Schäfer’s journey back to the region of her childhood does not easily revive these specters either. Details of interior spaces, or of the areas surrounding buildings or farms, are shown, such as gardens or tractors driving by. The people who are talking about the portraits of their family by August Sander are shown only through the gestures they make while dealing with the images. A forest seen in the background of a photo taken by August Sander also appears in one of Schäfer’s videos, yet this forest has meanwhile fallen victim to a storm. All of this work was preceded by the latter artist’s visits to the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the Ann and Jürgen Wilde Foundation of the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, and the Museum Folkwang in Essen to view various originals by Sander. Schäfer’s artistic investigations are based on these encounters and analyses as elements which, however, do not lend themselves to constructing a cohesive history, because such a history never actually existed, as Sander’s photographs have already shown: differences ranging from social, economic, and cultural to linguistic permeate this time in history and its representation, as is evident in every single photograph. Even landscape continues to be contaminated by these fragments of remembering and forgetting and to be populated by specters.

This circumstance is perhaps first and foremost another example of the specters of photographic history itself. Allan Sekula exposed as an ideology that which in exhibition projects like Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man (as of 1955) was celebrated as the universal language of photography. In Steichen’s view, this universal nature of photography corresponded to another universalism: “It demonstrates that the essential unity of human experience, attitude and emotion are [sic] perfectly communicable through the medium of pictures. The solicitous eye of the Bantu father, resting upon the son who is learning to throw his primitive spear in search of food, is the eye of every father, whether in Montreal, Paris, or in Tokyo.” So photography would be able to penetrate cultural distinctions and social differences in order to bring across the actual “essence” of “the human.” Here, representation becomes a cynical ethics governing the photographic image that, as visual-political propaganda material, is meant to boost sales of Coca-Cola around the world.

Yet this claim to cultural universalism could not be realized on even a few square kilometers of Germany during the first half of the twentieth century. After his wife died, Sander is pictured at lunch with his neighbors, sitting at the head of the table, the only one with a white tablecloth, an unmistakable sign of social distinction. So when Sandra Schäfer wonders how different fields and histories of images, knowledge, memory, and cultural habitus cross here, then it can perhaps only be said that even just marking the fault lines of these crossings seems tricky. And maybe such lines are not in fact identifiable in the photographs themselves, at least not if the people rendered still remain what they have always been: the portrayed. It seems to me that this whole project by Sandra Schäfer invites us to reflect on how the individuals portrayed can be turned into protagonists, and also to consider the stake they have always had in the images, what they have sought to appropriate through these images, how they have engaged with their own identity in these images, and thus what story they have tried to tell—or forget.

In the exhibition, the albums are seen in the videos as an archive, with the artist leafing through the album pages. In addition, pictures from these albums are grouped on ten tables. So the people populating these visual archives are extremely present in the exhibition. Yet at the same time they appear to be the big absent ones in the exhibition, especially because they are only present through the images. Such an ambivalent manifestation is reminiscent of exhibitions staged by earlier ethnological museums, with the intention of newly presenting their collection and making it accessible. It seems clear in retrospect that the individuals rendered in such post-ethnographic exhibitions were subject to a power that created these pictures, a power that we are used to calling colonial. The surveying, appraising, and classifying gaze of colonialism brought to life nothing more than colonialized bodies, or specters, who were subjected to a typology, made the subject of research, yet without being allowed an actual presence as subjects with their own history and culture. Maybe it is no coincidence that the artist, in her presentation, sought such proximity of form in order to make the visual archives of the Westerwald seem foreign to us in a new way, and also to seek within these archives a visual power of subjugation. August Sander’s endeavor to create a photo album of the typology of the German population, the famous People of the 20th Century, basically points in the same direction as the classifications and categorizations sought by Francis Galton in his composite portraits about eighty years earlier.

Sandra Schäfer’s rearranging of the visual archives might well point in the direction of counteracting the order of the archive itself by interrelating pictures that might not have been pasted next to each other into the albums. As to the missing images, we can only speculate. Ultimately, it is not a matter of exchanging one order for another or playing them off against each other, as Schäfer’s exhibition clearly shows, but of subverting the actual idea of order. If everything could have been different, then this history loses its unfolding exigency and becomes the object of a material and political practice, as postulated by Marx and others.

Then, however, the possibilities for agency also shift in the direction of those who posed for Sander’s pictures, causing Sander’s authorship to falter. The “visitation” would then need to be read from a different vantage point, for this would make it possible to grant the specters a place to manifest, or for us to think our way into the historical images or even fill them in. Ariella Azoulay calls this the °“civil contract of photography,” so as to strengthen the part of those involved in creating a photo. Maybe this “civil contract” harbors an opportunity to fundamentally decolonialize the history of photography, the history of archives, and our role in this history (in the images themselves and in being involved in researching these images)—if we move away from associating the act of colonization only with faraway lands to focus instead, very basically, on the state of subjugation under diverse regimes, including visual regimes. And perhaps it is not so far-fetched to start thinking about these archives, and thus about ourselves as well, as being, in a certain sense, likewise colonized.

Reinhard Braun

The artist Sandra Schäfer works with film, video installation, and photography. She explores the production processes of urban and transregional spaces, history, and image politics. Her artwork is often based on long-term research dealing with the edges, gaps, and discontinuities found in our perception of history, political struggles, and geopolitical spaces. Her work has been shown at various venues, including the 66th and 67th Berlinale, Berlin (DE), Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (DE), Depo, Istanbul (TR), La Virreina, Barcelona (ES), and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin. In 2020, her book Moments of Rupture: Space, Militancy & Film was published by Spector Books in Leipzig (DE).

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.