DLF 1874 - Die Biografie der Bilder

Infos

Duration

30.6.2012 – 2.9.2012

Opening

29.6.2012, 7pm

Exhibition talk

30.6.2012, 3pm

Ruth Horak and several of the artists present give a tour of the exhibition

With

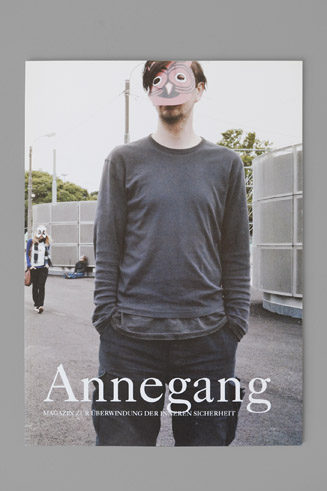

Annegang, Werner Feiersinger, Michael Höpfner, Rainer Iglar, Krüger & Pardeller, Tatiana Lecomte, Mahony, Dorit Margreiter, Christian Mayer, Susanne Miggitsch, Gregor Neuerer, Tina Ribarits, Constanze Ruhm, Günther Selichar, Michael Strasser, Anita Witek

An exhibition of works from the Austrian Federal Photography Collection – curated by Ruth Horak

Intro

When an artwork departs the studio to join a collection, it leaves the story of its creation behind. It disengages from all reflections and decisions that had hitherto bound the work to its author, and from all traces of creative activity. Factual information assumes the position of the original context: year, technique, dimensions, edition, price, inventory number (DLF 1874). It becomes part of the collection’s “stock”. The author alone is aware of the work’s inceptive history in all its facets: Which decisions led to the realisation of this work of art? What was tossed aside in the process? What people were involved at which locations? What other works were created in connection with this one? Which trips were taken? Which books read? If you trace the connection between the work and its author, a “biography of images” ensues—some shorter, some more extensive, significant or purposefully not circulated, some developed as planned, others with a life of their own. In this exhibition, all of the above meet—an inventory of ideas and products that breaks the works’ silence so that their stories may be told. Because: “Behind any work … stands the narrative which exists and ‘works’ on all levels, in the creation of these works as well as in the ‘understanding’ of them.”1

Volubility and reticence are the two poles between which the biography of images are spread, either widely ramified or narrowly focused. Sometimes the images belong to a whole construct that continually takes on new forms and generates many different parts, as in the case of Krüger & Pardeller. The point of departure is “Der Turm der Schatten” (The Tower of Shadows), a unique and autonomous 1:1 model of a shaded facade, designed by Le Corbusier for Chandighar. The artists have derived photograms and a light sculpture from Corbusier, thus lending an artistic form to his primary intention of coordinating light and shadow. Constanze Ruhm likewise spins a comprehensive referential web of films, theories, and genealogies around the set photographs from “Crash Site / My_Never_Ending_Burial_Plot” (2009). Tina Ribarits’s books, in turn, might be called speechless: with their respective origins erased, they have been reduced to black covers and empty white pages. Or the biography is just getting started and would rather not anticipate anything: “Apart from spam, I have received no further news”, notes Susanne Miggitsch in reference to “Ein Buch” (A Book, 2007–08), which she has sent on an indeterminate journey, while Dorit Margreiter’s “Manual of Foreign Dialects” (2006) is very concretely anchored in the film universe.

Read more →DLF 1874 – The Biography of Images

When an artwork departs the studio to join a collection, it leaves the story of its creation behind. It disengages from all reflections and decisions that had hitherto bound the work to its author, and from all traces of creative activity. Factual information assumes the position of the original context: year, technique, dimensions, edition, price, inventory number (DLF 1874). It becomes part of the collection’s “stock”. The author alone is aware of the work’s inceptive history in all its facets: Which decisions led to the realisation of this work of art? What was tossed aside in the process? What people were involved at which locations? What other works were created in connection with this one? Which trips were taken? Which books read? If you trace the connection between the work and its author, a “biography of images” ensues—some shorter, some more extensive, significant or purposefully not circulated, some developed as planned, others with a life of their own. In this exhibition, all of the above meet—an inventory of ideas and products that breaks the works’ silence so that their stories may be told. Because: “Behind any work … stands the narrative which exists and ‘works’ on all levels, in the creation of these works as well as in the ‘understanding’ of them.”1

Volubility and reticence are the two poles between which the biography of images are spread, either widely ramified or narrowly focused. Sometimes the images belong to a whole construct that continually takes on new forms and generates many different parts, as in the case of Krüger & Pardeller. The point of departure is “Der Turm der Schatten” (The Tower of Shadows), a unique and autonomous 1:1 model of a shaded facade, designed by Le Corbusier for Chandighar. The artists have derived photograms and a light sculpture from Corbusier, thus lending an artistic form to his primary intention of coordinating light and shadow. Constanze Ruhm likewise spins a comprehensive referential web of films, theories, and genealogies around the set photographs from “Crash Site / My_Never_Ending_Burial_Plot” (2009). Tina Ribarits’s books, in turn, might be called speechless: with their respective origins erased, they have been reduced to black covers and empty white pages. Or the biography is just getting started and would rather not anticipate anything: “Apart from spam, I have received no further news”, notes Susanne Miggitsch in reference to “Ein Buch” (A Book, 2007–08), which she has sent on an indeterminate journey, while Dorit Margreiter’s “Manual of Foreign Dialects” (2006) is very concretely anchored in the film universe.

Together with further factual-documentary studio shots of props, this work expo-ses the game of the lovely appearance of authenticity. When the three books are juxtaposed, the extent to which their biographies deviate, despite external similarities, becomes evident. Alongside volubility and reticence, the two extremes of construction and chance lend poles to the interposed biographies. Some images have been prepared long in advance, meticulously executed, carefully balanced in the post-production stage, thus representing the outcome of a longstanding explorative process: Günther Selichar describes his method of deconstructing media images as follows: “There came a point where I was more interested in what lay behind these images than in what they depict.” Anita Witek, too, extracts context from media images in that she divests them of their motifs and therefore also of their original meanings and biographies.

Other biographies are written by coincidence: “At dusk, a hermit wrapped in dusty sheets suddenly appeared in front of me as if from nowhere. … he hands me tea and porridge. His fingers are shiny with the butter he squeezes into my cup”, as Michael Höpfner recounts, speaking of his walks through the desolate landscapes of western China, often for weeks at a time—in his works we encounter the most literal form of “happenstance”. However, construction and chance are usually markedly proximate. Giving into chance just once, as in the case Mahony, fosters multifariousness: for each new exhibition event, Mahony rewrites the script to “Das älteste Stück Ding der Welt” (The Oldest Piece Thing in the World, 2007), first giving it a body and then successively extracting its substance until it has almost completely disappeared.

If we wanted to sort the images according to a specific biographical aspect, place of origin would be a relevant category—for one of photography’s great callings has been to bring home pictures of faraway places. This also reflects the nineteenth-century predilection for decorating European walls with images from the exotic colonies, usually in an unquestioning and decontextualising way—a practice to which Christian Mayer takes recourse. The contemporary places of origin are then again more factual, like Le Corbusier’s monastery La Tourette, which Werner Feiersinger downright palpates—from the overall structural complex, by way of the choreography of the visual axis, to the unusual solutions that Feiersinger, a sculptor, finds especially fascinating: “In place of balustrades, boulder-like objects with peculiar hollows in which plants can be grown prevent access to steep slopes.”

The places of origin all too frequently affect the biographies of the artists themselves: “Women are obliged to comply with the country’s dress code: the head, neck and buttocks must be covered. The Iranian women travelling with me from Vienna began to cover up even before the aircraft landed”, with Tatjana Lecomte thus linking her own experiences to her decision to avoid tourist images. The bmukk photographic studio in New York has also inspired countless works that have more or less directly succumbed to the site’s influence. Michael Strasser: “… tearing it up piece by piece and stacking it with a fragility that left it vulnerable to a sudden gust of wind or movement of bodies in the space”2—thereby making the photograph a work of art, but also a document. Likewise in New York, Gregor Neuerer observed how cars spent days upon days parked at the Staten Island Ferry Terminal, an epiphenomenon of the way in which work markets have developed, thus opening up topics related to the economic pressure shouldered by individuals. As one of the many excesses in this capitalist world he invokes the “junkspace” that Rem Koolhaas had so trenchantly defined. Annegang is both artists’ collective and magazine title at once—its biographies overlay one another: Annegang “urges collective action, intervention in everyday politics and a dissident understanding of art. Of course art can look nice—it just has to keep interfering”. Just as much need for action is called for, according to Rainer Iglar, especially when art is noncommittal and adaptable and when “the collector’s tasteful combination” takes centre stage, for private collections in particular harbour their own stories, with photography only able to strip away an extremely thin layer.

“He consequently possessed a marvellous collection … he set apart, for the unalloyed pleasure of his eyes, plants that were elegant, rare, and of exotic origin …”3 “He had wanted, to satisfy his intellect and give pleasure to his eyes, a few evocative works which would project him into an unfamiliar world, revealing to him evidence of fresh possibilities …”4

The Austrian Federal Photography Collection was founded in 1981 and today comprises nearly 8,000 works by 470 artists.

1 Ilya Kabakov in the introduction to Der Text als Grundlage des Visuellen, ed. Zdenek Felix (Cologne: Oktagon, 2000), p. 237.

2 Fatoş Üstek, “Einleitung,” in Michael Strasser, Domestic Sculpture Garden (Salzburg: FOTOHOF Edition, 2012), n.p.

3 Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature, trans. Margaret Mauldon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 72–73.

4 Ibid., p. 44.

Installation Views

Opening

Exhibition talk

Partners/Sponsors

Eine Ausstellung aus der österreichischen Fotosammlung des Bundes