once documentary

Infos

Opening

Thursday, June 5, 2014, 7 pm

Duration

6.6.–7.9.2014

Lectures accompanying the exhibition

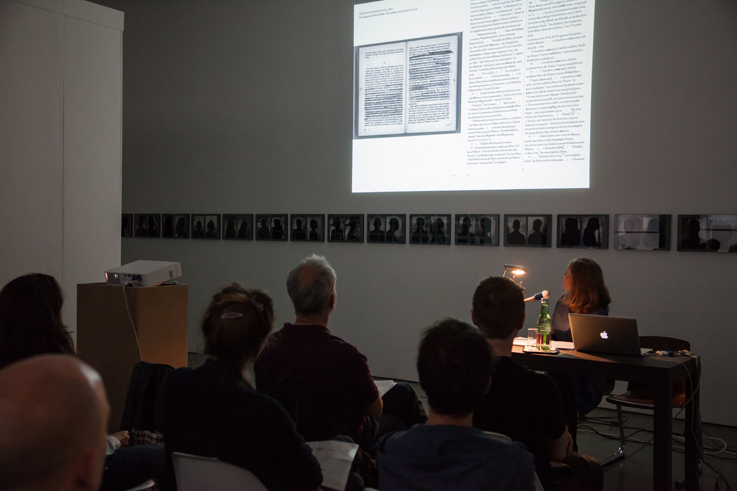

»Speculative Realism, Performative Documentarism«

with T.J. Demos and Kathrin Peters

4.9.2014, 6 pm

Opening hours

Tuesday – Sunday 10 am– 5 pm

Extended opening hours

One Thursday each month the exhibition stays open until 9 pm

26.6.2014, 6 pm Exhibition talk

10.7.2014

With

Sven Augustijnen (BE)

Eric Baudelaire (FR)

Peggy Buth (DE)

Maryam Jafri (US)

Intro

In recent years, discourse in the art world on documentarism has provided opportunities to repeatedly reflect on the critical role and the function of photographic documentary images within contemporary visual regimes. On the one hand, it is said that no one believes in the truth of images anymore, yet on the other, we have been warned not to become lost in an idle state of reflexivity related to the constructed nature of images. In the (also relatively new) mass media, documentary images oscillate unchecked between the indices of fiction, authenticity, and fetish, between proof and manipulation, critique and affirmation, and they traverse disparate and opposing contexts. These media still continue to produce images in which events and history appear to densify, images that are shown again and again, occasionally even becoming icons.

Yet this circulation rarely concerns a dispositif of just the images themselves, for they are almost always framed by rumour, communication, various channels of information, but most of all by narratives, commentary, and text material. The dispositif of—documentary—images is not inherently visual. As Stuart Hall noted in 1984: °“[T]here is no such thing as ‘photography’; only a diversity of practices and historical situations in which the photographic text is produced, circulated and deployed.” The exhibition “once documentary” is interested in practices and situations in which the documentary image emerges and is applied—as vehicle, marker, comment, reference, or placeholder for a gap that cannot be occupied.

Read more →

once documentary

In recent years, discourse in the art world on documentarism has provided opportunities to repeatedly reflect on the critical role and the function of photographic documentary images within contemporary visual regimes. On the one hand, it is said that no one believes in the truth of images anymore, yet on the other, we have been warned not to become lost in an idle state of reflexivity related to the constructed nature of images. In the (also relatively new) mass media, documentary images oscillate unchecked between the indices of fiction, authenticity, and fetish, between proof and manipulation, critique and affirmation, and they traverse disparate and opposing contexts. These media still continue to produce images in which events and history appear to densify, images that are shown again and again, occasionally even becoming icons.

Yet this circulation rarely concerns a dispositif of just the images themselves, for they are almost always framed by rumour, communication, various channels of information, but most of all by narratives, commentary, and text material. The dispositif of—documentary—images is not inherently visual. As Stuart Hall noted in 1984: °“[T]here is no such thing as ‘photography’; only a diversity of practices and historical situations in which the photographic text is produced, circulated and deployed.” The exhibition “once documentary” is interested in practices and situations in which the documentary image emerges and is applied—as vehicle, marker, comment, reference, or placeholder for a gap that cannot be occupied.

In 2009, Dieter Roelstraete spoke of the “historiographic turn in art”, of contemporary art’s obvious—if not obsessive—fascination with archiving, forgetting, remembering, looking back, reinterpreting, reenacting, or, in short: with the past. This diagnosis becomes interesting at this juncture, especially because it also describes the circumstance by which image production must always also conceptually engage in its relations with a narrative and the related mechanisms that have constructed this narrative, that have invested it with plausibility and thus authorised it. Now this interest in history has less to do with nostalgia and more to do with a re-evaluation of the fundaments of the present—during times of ongoing crisis. The continual questioning of the documentary—photographic—image thus relates to a crisis of plausibility and of valid—political, social, economic—agreements. If it at best seems difficult to foster reliability when it comes to present-day events, then something of an “archaeology” of the present attains intensified meaning. Agreements about the various forms of knowledge production thus automatically begin to falter. And documentarism can no longer be conceived as a self-evident practice of perception and of the gaze (concepts that may hardly even be considered beyond questions of power and control), as a practice involving the “shooting” of a picture at the right time or being an eyewitness (of what?). Under such premises of “blurred relations” (“Unschärferelationen”, Hito Steyerl), documentarism actually describes a practice that takes the conditions of these pictures into account, a practice that shifts the documentary image away from its fixation on questions of theory related to the images and into a context populated by theories of society, theories of history, and theories of the political: What is being remembered? What can be discerned about history based on the pictures? Which texts are written about these pictures? The artists in the exhibition °“once documentary” take different approaches to addressing these questions related to the construction of history, and thus also to the construction of collective knowledge.

The title “once documentary” is not meant to convey that the documentary can be left behind, but it does imply viewing realities—even historical ones—as something that is constructed through conflict about their meanings, conflict that is also subjected to that which has been and is still presented for view. Indeed, representation is still “a highly political [process] that involves the power to make meanings both of the world and of one’s own place within it” (John Fiske). The artistic contributions to the exhibition all revolve around this issue of possessing the power to engender meaning, to write and establish history, and thus to suppress other possible meanings, other possible histories. So the documentary does not primarily emerge as a formation of images, but rather first and foremost as a practice of knowledge production which demands that we move beyond simply seeing to pass through a perceptual process (Elizabeth Cowie). These are images that are enmeshed in a statement or a discourse where reality is constructed as knowable and is presented to us as—controversial—knowledge to be perceived. “Assembling the present so that it might be conceived differently, liberating time from its rhythm—today this would be the job of a documentary language of things. The subject of the documentary image is thus neither its object nor reality as such; instead, it is the present day that can allow it to flare up” (Hito Steyerl).

Sven Augustijnen

On 17 January 1961 the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo was executed: Patrice Lumumba, Pan-Africanist and leader of the independence movement. Just over six months earlier, on 30 June 1960, the republic had asserted its independence from Belgium, the former colonial power. Party to the murder were said to be the Belgian government, the mining company Union Minière, the United Nations, and, most prominently, the United States—based on fears that Lumumba’s politics, which were purportedly oriented to communism, threatened to diminish the influence of Western powers in Congo.

In his project “Spectres” (2011), Sven Augustijnen attempts to reconstruct the history of this murder. Still today the murder casts a cloud over the—barbaric—role played by Belgium as the former colonial power in Congo. A board of inquiry commissioned by the Belgian government, which published results in 2001, was unable to solve the murder case and managed only to acknowledge that “certain members of the Belgian government and other Belgian protagonists carry moral responsibility for the conditions that led to Lumumba’s death”.

“Spectres” is centred around the eponymous, 100-minute documentary film, which in turn revolves around Jacques Brassinne de la Buissière, a senior Belgian official in Congo at the time of Lumumba’s murder. Brassinne published a comprehensive book in which he essentially reaches the conclusion that “it was an affair under Congolese”. The film follows Brassinne’s stories and conversations, as amongst others with Lumumba’s widow. Also documented, most importantly, is the attempt to locate the exact site of execution, including the tree to which Lumumba was tied, believed to be littered with bullet holes. Initially engaging in full with Brassinne’s protagonist role, the film slowly reveals his obsession with asserting innocence—that of the Belgian administration at the time, to which he belonged, and thus simultaneously also that of today’s Belgian government. This is an obsession that is focused on the desire to finally leave colonial history behind, to bury the—political, racist, nationalist—“spectres” that continue to threaten the fragile solidarity between society’s elite and postcolonial immigrants. Besides the film, the project “Spectres” encompasses a book with comprehensive source material, likewise released in 2011, as well as other books, magazines, audio recordings, photographs, and archived material that have been compiled through extensive research.

The project strongly focuses on the potentiality of an—authoritative—construction of history. The ever-recurring facticity, or the wish to ascertain facts and thus establish a reality, causes this desire for objectivity to seem like a phantasm that moves desire itself to the forefront. Accordingly, controlling the historical narrative also implies controlling (and quelling) the meaning of these events for the present. Yet, as we have long known, the unconscious always returns. The spectres of colonialism continue to inhabit present-day language and social hierarchies, thus continuing to control the production of visibility.

Eric Baudelaire

Eric Baudelaire takes a similar approach to referencing suppressed history in his project “Anabasis” (2011), namely, the Japanese Red Army active in Lebanon in the 1970s. Fusako Shigenobu was a leading figure in Japan’s student movement of post-war years and also a member of the Red Army Faction, modelled after the German group. In order to internationalise the revolution, she contacted the Palestinian Liberation Front in 1971 and travelled to Lebanon for the first time. It was there that she founded the Japanese Red Army and spent nearly thirty years in exile before being extradited to Japan in 2000. It was in this year that her daughter May first set foot in Japan. Masao Adachi, in turn, began working on creating radical cinema in the 1960s, in the scope of students’ film clubs of that time. Following his controversial participation in the 1971 Cannes Film Festival, he likewise travelled to Lebanon to work there on a film called °“Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War”. Following the call to armed resistance propagated in the movie, Adachi joined Shigenobu’s Japanese Red Army in 1974 and ceased making films. In 2001 he was imprisoned for eighteen months before being extradited to Japan. Today Masao Adachi lives in Japan without a passport or any opportunity to leave the country.

The film posited at the centre of Baudelaire’s project, “The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years without Images” (2011), revolves around exile, revolution, landscape, and memory. Alain Badiou described the “Anabasis” motif in his book The Century (2006) as a movement of the twentieth century, as a return to origins, as a solid construction of innovation, as an exile-based experience of beginnings. This “Anabasis” harks back to an ancient myth that deals with the collapse of all order and also with a group of warriors who embark on a winding path home, which only retrospectively can be considered a favourable homecoming. Baudelaire takes this motif as a point of departure for thematising the odyssey, aimlessness, and lack of restraint found in socialist projects of the twentieth century, which was not only seen to disappear through a quasi-universalised, neoliberal societal model after 1989, but also stigmatised, together with any alternatives, as totalitarian.

This—political and, yes, also violent—history has come to an end, has been immobilised, has been damned to a nature of fixedness. Baudelaire vicariously films those pictures in Lebanon that Adachi imagines, but which remain inaccessible to him—a utopia that remains literally out of reach, that has come to an end. Yet the film may by no means be considered to romanticise armed resistance; it tells the story of failure, of an odyssey that cannot be deemed a favourable homecoming. At the same time, the protagonists become a metaphor for the collapse of a twentieth-century utopia that yearned not only to devise but also to realise another form of politics and community. Did the century ever return home?

Peggy Buth

On 22 October 1904, the Städtische Völkermuseum (Municipal Ethnology Museum) was founded in Frankfurt on the Main. The museum founder and first director was Bernhard Hagen, who in 1900 had already established the Frankfurter Anthropologische Gesellschaft (Frankfurt Anthropological Society). While working as a tropical doctor on the island of Sumatra and in Papua New Guinea, Hagen compiled an extensive archive of photographs that he went on to publish, among others in his 1906 book Kopf- und Gesichtstypen ostasiatischer und melanesischer Völker (Head and Facial Types of East Asian and Melanesian Populations). In early 2014, Peggy Buth realised a comprehensive project for the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt, as the museum is now called, in which she references, among others, Hagen’s pictorial archive on missionaries.

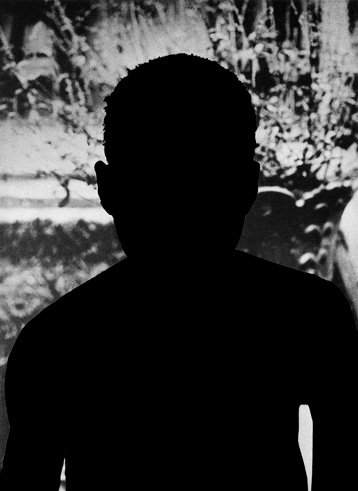

In continuing this project, which is called “All of Us: Trauma, Repression, and Ghosts in the Museum”, the artist is producing a new piece for “once documentary”. The work pairs up photographs originating from the collection of the museum founder Bernhard Hagen, who photographed many of his patients, usually from a frontal perspective as a portrait and then a second time from the side. Peggy Buth has reworked these photographs in two ways: for one, she has emphasised the respective background, but the artist has also clearly transformed the portraits into silhouettes. Any trace of individuality has been removed from the pictures, with only the background of the silhouettes referencing concrete situations: sometimes interior space is recognisable, while in other cases it appears to be a studio context.

The surveying, appraising, and classifying gaze has evoked nothing other than colonialised subjects who were subjected to a typology, who were the topic of research, yet who do not make an appearance as subjects. At the same time, these silhouette-like photographs highlight a dominating gaze, a dominating visual regime that governs this act of disappearance—the power of a gaze that conveys something visual, that engenders a visibility that has always transformed those that it touches and simultaneously subjugates into something absent, adulterated, occlusive. Among other things, Peggy Buth illuminates the gaps in this representation: the empty spaces of those who cannot occupy the place of the subject and the gaps of those who cannot perceive this space as a place of subjectivisation, and also of representation. Abigail Solomon-Godeau has wondered whether the documentary act might not imply a dual act of subjugation: first, in the social realm that the victim has spawned; and second, in the regime of the image itself that is produced within the same system and for the same system, which creates the conditions facilitating its re-production. Buth’s intervention gives rise to an exemplary space where vision as a circulatory power can be perceived, yet which literally cannot be seen by those who are being subjugated, thus transforming them into “ghosts”: revenants whose presence is fostered merely through non-representation. Ultimately, this is a technique for reconstructing the presence of these ghosts in their absence, so that the shuttered and finalised history of their representability may be reopened—an unredeemed history that can be neither forgotten nor vanquished.

Maryam Jafri

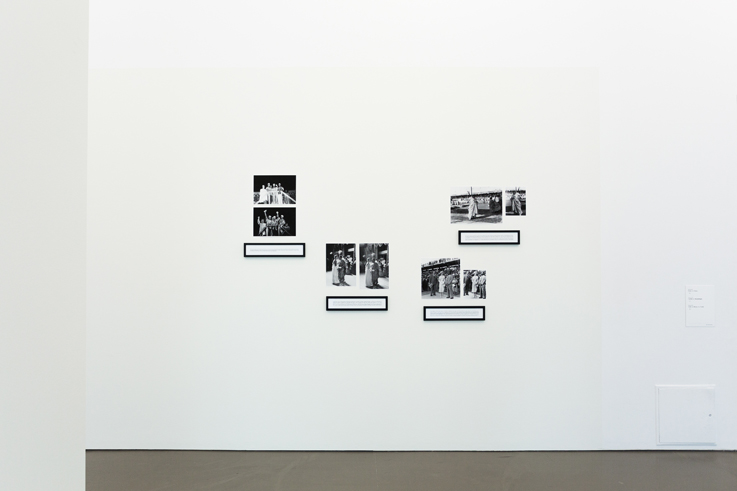

“In 1995, Mark Getty and Jonathan Klein founded Getty Images to bring the fragmented stock photography business into the digital age. And that’s exactly what they did. We were the first company to license imagery online—and have continued to drive the industry forward with breakthrough licensing models, digital media management tools and a comprehensive offering of creative and editorial imagery, microstock, footage and music.” In researching the Getty Images website, Maryam Jafri came across pictures originating in Ghana’s federal archive, with which the artist was already familiar from the research she had conducted for her project “Independence Day 1936–1967” (since 2009). The information that Getty has published about these images does not always correlate with the Ghanaian information. This is even more evident since these are not just any photographs, but rather those taken on the day the African republic achieved independence. The more checking the artist has done, the more discrepant information she has found, along with manipulations made to the pictures themselves. She discovers these same discrepancies in the online catalogue of the Corbis Corporation: “Corbis is a creative resource for advertising, marketing and media professionals, providing a comprehensive selection of stock photography, illustration, footage, and fonts for global licensing.” Both companies have purchased numerous image archives worldwide in recent years, with the aim of commercially exploiting the content. Corbis, for example, bought the Paris agency Sygma for 20 million dollars in 1999. Getty, in turn, picked up the archival conglomerate Hulton Deutsch for 17 million dollars in 1996. With such accumulation of photographs (also of historical nature), in many areas the companies possess monopolistic control over which images are circulated and which history may be construed about the images. In his influential essay “The Body and the Archive”, Allan Sekula speaks of the archive as a “truth apparatus” that cannot be solely described by the visual. Over time, this truth apparatus becomes ensconced by a dispositif of control, possession, and appropriation that is dominated by private enterprise. The archive has indeed become a privatised apparatus of truth.

In Jafri’s “Versus” series (2012), the artist adjacently positions the contrasting image versions from the different archives, accompanied by a text that offers information about the captions on the reverse side, and that also sometimes reconstructs the path taken by the respective picture through the private archives. While the photographs themselves are shown without frames, each text is presented in a frame. The importance of the accompanying texts is therefore highlighted through this presentational approach—again, we are dealing with the construction of knowledge and history.