Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński

Infos

Award Ceremony

– cancelled –

December 10, 2021, 6 pm

Exhibition space Camera Austria

In the frame of the exhibition opening of Sandra Schäfer

Laudatio: Nora Sternfeld

Due to the current situation, the prize had to be awarded without a ceremony this year. All the same, we are very pleased to share on our website a shortened version of Nora Sternfeld’s laudatory speech, the Words of Greeting by Günter Riegler, City Councilor for Cultural Affairs, and the video work Unearthing. In Conversation (2017) by the awardee.

Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography by the City of Graz 2021

Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński

Description

The Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography by the City of Graz, which is awarded biennially, will be bestowed on Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński (born 1980 in Vienna) in 2021. The jury founded their decision to honour Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński with this award on the following statement: “The Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography by the City of Graz 2021, bestowed this year on Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński (born 1980 in Vienna), is honoring an artist whose explorative photographic work is closely tied to the researching and unsettling of colonial history and its legacy. Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński creates photographs, but also collages, films, performances, installations, and writings, which scrutinize how the experiences and narratives of Black individuals are suppressed or marginalized. Her sharp analysis of visual regimes and hegemonic epistemologies is based on research conducted in collections, museums, archives, and libraries. As part of her artistic research, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński interlaces analysis with fiction and documentation with imagination. This results in works of art that are piercing and poetic in equal measure, deliberately open, at times fragile and hypothetical—works that facilitate critical insight into how colonial perspectives and matrices of power live on, while at the same time presenting new imaginaries grounded in the Black Radical Tradition.”

Jury

Natasha Christia, freelance curator and author, Barcelona (ES)

Chiara Figone, publisher, Archive Books, Berlin (DE)

Matthias Michalka, curator at Museum moderner Kunst, Vienna (AT)

Reinhard Braun, publisher Camera Austria International, Graz (AT)

The Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography by the City of Graz was established in 1989 and is bestowed every two years on an artist who has published a noteworthy contribution in the magazine Camera Austria International and has made an important contribution to contemporary photography. The prize-money is Euro 15,000.

Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński’s work has been published in Camera Austria International Nr. 153/2021

Word of Greeting by Günter Riegler, City Councillor for Cultural Affairs

For over thirty years the City of Graz has been granting, together with Camera Austria, the Award for Contemporary Photography. This year, the highly specialized international jury suggested honoring Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński. I was happy to support this decision and passed it along to the city senate for a vote on the matter. I am very pleased that, after Lebohang Kganye (ZA), Jochen Lempert (DE), and Annette Kelm (DE), now Ms. Kazeem-Kamiński as an Austrian artist has been chosen. My thanks are extended to the jury and, most especially, to the artistic director of Camera Austria, Reinhard Braun, for the outstanding realization of this process. I am delighted that we will be able to admire the artwork of this year’s Camera Austria awardee at the Kunsthalle Wien until March 2022.

Your city councillor Dr. Günter Riegler

On a Search, in Spite of Everything

Laudatory Speech for Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński

by Nora Sternfeld

Three photos show a Black woman against a monochrome background: red, black, and green—the colors of the Black Consciousness Movement, and of the Pan-African flag. The figure portrayed is not looking into the camera; she is looking away from our gaze and into the future. The photo series is titled In Search of Red, Black, and Green (2021). It denotes a search, a search for a utopia, but also a search for forms that are themselves familiar with the fragility and complexity of showing and searching—and with the fragility and complexity of utopia.

Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński’s works find their own formal language. They are unyielding in their persistent search for forms and words that confront what has now often been lost irretrievably, can no longer be shown, and what is nevertheless testified by omissions, fractures, and traces.

Racism leaves its traces: Even if the epistemic violence of colonial archives and historiographies did not envision any history for Black people. Even if the systems and classifications of museums and institutions adhere to Western views, which are able to see exoticism, but not equality. Even if the violence is put into cynically beautiful words. And even if the traces of enslavement and abduction, of humiliations, rapes, exploitation, and massacres are supposed to be covered up, traces and remainders of violence are nonetheless left. In the middle of the powerful divisions of the world, in the thick of what has been transmitted, but also—and specifically—in the omissions, fractures, and contradictions of the archives, testimonies to Black life and survival are to be found, traces of courage, dignity, waywardness and self-will—in spite of everything.

In Remembrance to the Man Who Became Etched into History as “Der Aschanti an der Akademie” (2021), for instance, is the title of one of the artist’s installations. In her works Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński enters into dialogue with persons who are haunting the archives. They are only to be encountered as specters, because they were dehumanized by the practices of colonialism and the racist gaze. Kazeem-Kamiński wants to get to know them, and to commemorate them; she establishes links to them and develops the power of her works from the impossible possibility to connect with them in the middle of the infrastructures of the archives and their powerful attributions. She portrays persons who were deprived of their names, like that Black model at the academy, whose portrait, as the material shows, was not present to depict anatomy, but was instead used to find expressions of exoticism and the contrast to white anatomy. Or like that man who would become known as Angelo Soliman, who in the course of the Atlantic slave trade was kidnapped as a child and taken to Vienna, was given a fantasy name in the aristocracy there, and whose body was stuffed after his death and exhibited in Vienna. Or like Yaarboley Domeï, a woman from Western Africa, who was forced into the violent forced labor of displaying herself within the framework of so-called “Völkerschauen,” or human zoos. In several works Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński engages with an open letter that Domeï wrote in 1896 and was published in the newspaper Wiener Caricaturen. The letter, which she was able to have translated, tells of the violence and the voyeuristically goggling gazes, and also reports proudly of the resistance against the behavior of the audience and appeals for her return to Ghana. To make it possible to hear these stories of violence and self-assertion and thus bring the power of the struggles to survive to life, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński appropriates the techniques of powerful infrastructures, works with the means of the archive and the museum, communicates with the stories handed down, but without closing the gaps that a racist writing of history makes gape in a painful way for an antiracist reconstruction of a racist history.

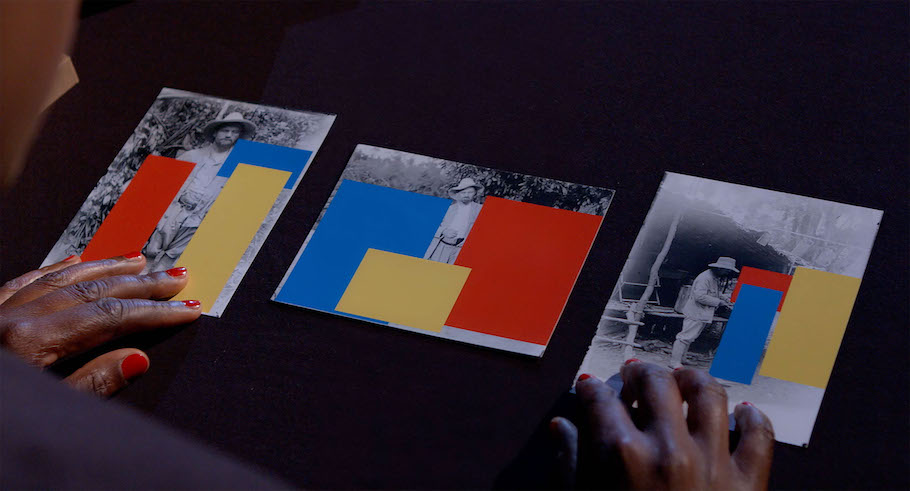

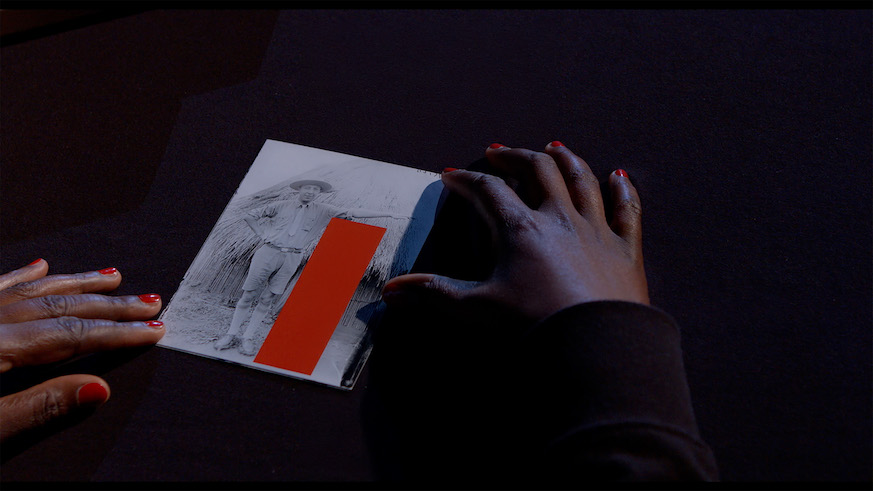

She works with the means that are available, as contaminated as they might be, and appropriates them against themselves. This also includes the violent history of photography. In her video Unearthing: In Conversation (2017), she communicates with the specters of historical Black persons, who she is only able to encounter based on racist colonial depictions, photographic portraits by an ethnologist. She insists on an encounter between the generations, and creates links by concealing the racist representations with blocks of red, blue, and yellow color. Here, too, the blocks of color make reference to African flags, to the history of liberations, to symbols of utopias. She speaks about the blocks of color, about the need to conceal in order to show, reflects on the violence of the racist material. And she then looks into the camera and says: “And I don’t even like flags.” In spite of their contradictory character, the artist once again makes the means themselves the topic, with which she insists on a resistant “we,” on working on a future.

The utopia also has its fractures in the forms of Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński: She puts herself in a relationship with the right to history, with the burden of the past vis-à-vis a different, possible future, in which, she knows, the sun will not always shine. This future is an engine that propels her. And she thus actually does not want any grand words in her honor, but prefers that we speak in such a way as we simply speak with one another, she says, and that she knows that this “utopia will also be a huge amount of work, that it will not be without its problems. And,” she says, “it is necessary to do this work.”

Insights

Video