Press information

Ana de Almeida & Huda Takriti

(In)verso. Between the Lens and the Archive

Infos

Press preview

13.9.2024, 11 a.m.

Opening

13.9.2024, 6 p.m.

Artist’s tour with

Ana de Almeida & Huda Takriti

in the frame of steirischer herbst Partner Program tour

28.9.2024, 12:30 p.m.

Duration

14.9. – 17.11.2024

Opening hours

Tue – Sun and bank holidays

10 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Idea and concept

Anna Voswinckel

Press Information

What do we ask of images?

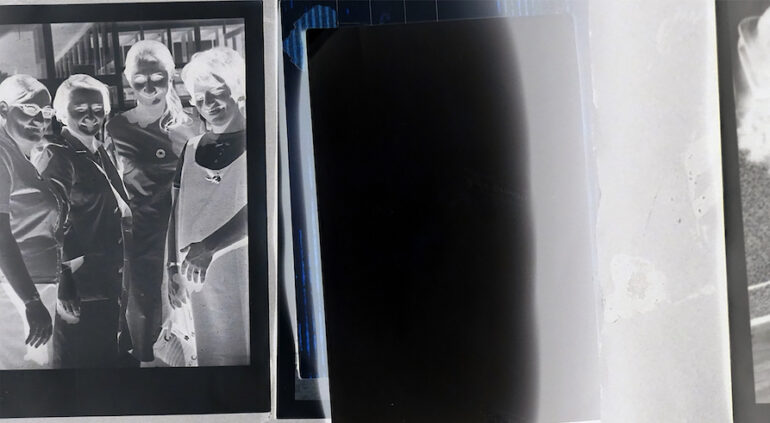

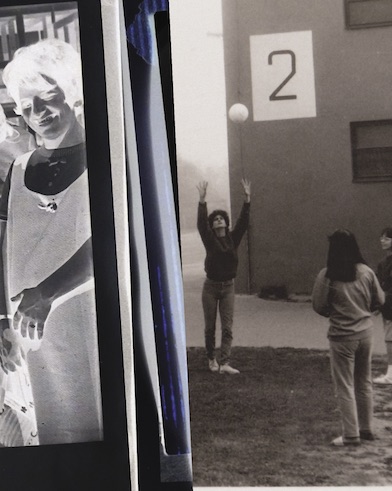

Through video and collaged installations that feature her mother’s and grandmother’s photographs, stories, and prized things, Huda Takriti meditates on the nature of familial memory and knowledge production as women’s practice. She narrates the memories of her mother and grandmother, as generational knowledge still unfolding. Both her mother’s and her grandmother’s hands appear again and again in the video On Another Note (2024), holding scissors that cut fabric, turning the pages of photo albums, and gesturing as they explain. Her mother’s hands, captured by her daughter, link generations, bodies thousands of miles apart, and the knowledge they carry.

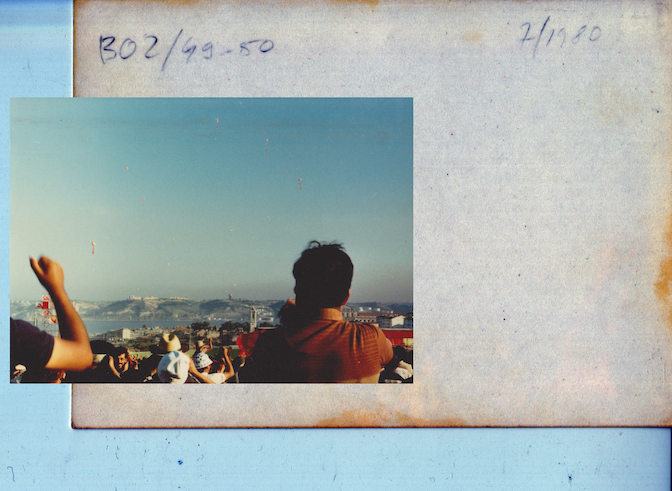

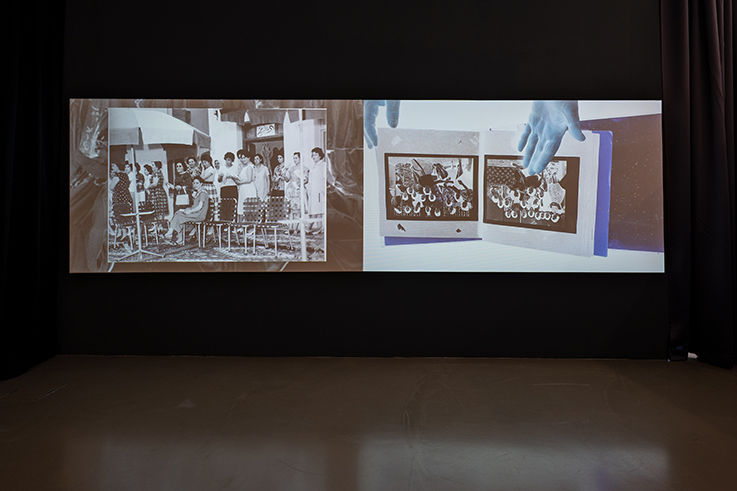

Ana de Almeida, in turn, examines family photographs—pictures from her father’s youth, taken alternately in his home country of Portugal and as a student in communist Czechoslovakia, between the years after the Carnation Revolution (1974) and just before the Velvet Revolution (1989). The images are filled with revolutionary fervor and empty of fixed archival documentation, leaving them open to the artist’s extra-historical and open-ended interpretations. They become hosts to the artist’s conceptions. De Almeida amplifies the presence of the family “shoebox of images,” so to speak.

As both practices are collage-like in their address of memory and history in times of social unrest, I will move back and forth, to meditate on memory and migration. Huda Takriti and Ana de Almeida think about what we ask of images, and what we ask of the things our family leaves behind in the long journey of migration or displacement. Particularly given the ubiquity of vernacular imagery in our lives, wallpapering our social media and web-based visual landscapes, their questions bring to relief the slippery political borders of things we take for granted as oppositions, the institutional and the familial history in the narration of social life and its upheavals.

Takriti draws from theorizations by the cultural theorist Edward Said, who poignantly argued for the criticality of undermining state narratives—particularly those of the colonizing state—through counter-archives. While Takriti takes up this charge, her project also tacitly acknowledges that “big stories”—the monumental counter-archive—cannot account for histories yet unfolding. As her family remains displaced and far from their home of Palestine, and as the Nakba remains an ongoing condition rather than a concluded proposition, what monumental story holds the weight of a family’s look to an unrecoverable home? Perhaps the hands of her mother carry such weight.

De Almeida’s father was one of many young idealists who made their way to Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, as part of a larger East Bloc program during the Cold War era to recruit students from the “developing world” to communist nations. He was a member of a generation that participated in massive sociopolitical change, that witnessed military and civil resistance to Portugal’s authoritarian regime. Erupting into a popular resistance movement for a time, the Carnation Revolution bolstered a euphoric optimism in greater shared governance. Her father’s experience led him to look for different manifestations of resistance in his home and host countries, which he photographed. These photographs offer a connected iconography of revolutionary fervor that is readily accessible even to the contemporary viewer—of tanks, of youthful crowds, and of peace signs and raised hands. Yet, the particulars of their varied histories are left opaque in her father’s personal archive. The images in Ana de Almeida’s works do not index moments, as the photographic document is expected to do in institutional histories. Rather, they harken to her father’s life, to her life as a member of a postrevolutionary generation, and to the uncertain futures contained in these decades-old images. The pictures carry the promise of change and its attendant fervor, not the foreclosure of historical events.

There is a desire we can have for images, which both artists variously describe as a kind of hosting or a place of longing and projection. The theorist Pierre Nora described this function as lieu de memoire, which exemplifies the heightened symbolic meaning a thing can take on in familial and cultural memory. But such a symbolic meaning is only “hosted,” when the past is acknowledged as unrecoverable. In Nora’s words: “Our interest in lieux de mémoire . . . has occurred at a particular historical moment, a turning point where consciousness of a break with the past is bound up with the sense that memory has been torn—but torn in such a way as to pose the problem of the embodiment of memory in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. There are lieux de mémoire, sites of memory, because there are no longer milieux de mémoire, real environments of memory.”¹

For de Almeida, that nostalgia is for revolutionary fervor itself, a nostalgia still alive long after such dreams propelled young people to the streets in the 1960s and 1970s. Thus, she unearths the resonance of the photographs by starting with and honoring her artistic intuition and familial affective knowledge, then proceeding to external inquiry and corroborative research. Her works take a retrospective look at what it meant to belong to a revolutionary generation, and at the young man who would become her father, but also at the participants and onlookers whose collective force meant potential. Through such retrospection, her works also invite the contemporary viewer to scrutinize the self-evidence of our political moment.

Émile Durkheim, who theorized on collectivity and revolution, argued that collective investments have the character of a categorical imperative—a self-evidence that confirms the logic of (the right) revolution. In 68: Prague in Lisbon (2024), de Almeida superimposes her voice on missing audio tracks belonging to street interviews conducted in Lisbon by the Portuguese national TV broadcaster RTP in 1968; the content involves the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union–led Warsaw Pact troops, which had unintended consequences for the unity of the communist projects worldwide. Guided by research on the Portuguese press coverage of the time, and even lipreading, de Almeida lets her own subconscious desires flow through the cracks of the revolutionary promise. Together with two other videos, April Words (2024) and November Words (2024), in which the artist invites Portuguese and Czech sign language interpreters to translate historical terms directly related to the Carnation and Velvet Revolutions, she seems to ask, instead: Are the semiotics of revolution fungible, fixable, malleable, or other? Social order and revolutionary faith are cleansed of consequences and interrogated in their representations. However, this maneuver is not cynical.

Theories and abstractions aside, fierce nationalisms gather power and monopolize truth and patriotism now, through and against the photographic image and its claims to evidence. The populist demagogue claims greater immediacy (read: less mediation) of presence and meaning, made flesh in the throng of crowds in the thrall of nationalism. The photograph is impoverished. De Almeida’s invocation of the photograph as pure potential is a denial of the repressive state. To the contrary, she summons Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s conception of the photograph as a civil contract—as a means of enfranchisement and manifestation of participation and consent, despite the political condition.

The Parable of the Archive

In an interview with the artist, Huda Takriti shared a spark that had lit her critical inquiry into how documents form the material ground of cultural memory and desire. She spoke of The Battle of Algiers (1966), Gillo Pontecorvo’s historical fiction film on the events surrounding the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62). She had learned that in the absence of adequate footage of Algerian resistance efforts, the film had functioned as a default historical archive for Algerians. Although I know little of the performance of the film in the Algerian imagination, it seems to me that Takriti was explaining how images and documents can fluidly move into archival gaps—gaps which are the predicate of (colonial) marginalization and/or erasure. The image seeps into the archive’s gaps like the dispersal of water on uneven ground, mapping institutional history’s occlusions even as it seeks to fill them through fictions. (As we know all too well, fictions also have their place in government-sanctioned narratives.) Takriti’s story tells one of desire for the document, asking the fictional film to be a place of memory in absence of a photographic record. Perhaps more importantly, her anecdote reveals the significance of imagery in the constitution of cultural memory in the modern age, and the significance of memory in fostering collective hope.

Let us extend Takriti’s “parable of the archive” to her own practice, which navigates her family’s histories even as it obliquely addresses the unspeakability of the displacement experienced by her family and other Palestinians. For as the ongoing war reveals, the politics of erasure and visibility is ongoing, not historical. As we think about migration and memory in the context of the archive, then, let us remember that memory is the fabric that enables a continuity with the lost home. As the archive actively suppresses and erases its margins, and personal and cultural memory are hyper-politicized, how is continuity retained in the body and in the things kept by those forcibly displaced?

Textiles made by Huda Takriti’s grandmother were lovingly found and maintained by her mother. Her mother, in turn, was also an artist of cloth. She crafted dresses and made a place for herself in her adopted state of Kuwait. The textile is woven into Takriti’s images as the substratum of her family’s history, and through tales of textiles we learn of hopes, ambitions, and happenings. Their images accompany family photos and pictures of her mother’s life, in the vehicle of the family album in On Another Note. Functioning as informal archives of the family, the family album is also the loving work of her mother and grandmother, and the vessel they chose to hold pictures so dear to them. The narrative the artist’s mother offers is contingent, private, and thoughtful. There is no clear beginning or end to the story, nor an effort to inscribe a linear moral arc to it. Her rejection of beginnings and ends is conscious.

Takriti observes that narratives are containers that exclude as they preserve. She does so by drawing on work by the literary scholar Albrecht Koschorke. “Especially in the narrative reconstruction of conflicts, the choice of beginning is consequential, because so to speak the meter of the injustice inflicted one of the conflicting parties, justifying its resistance, is running from the specified beginning onward.”²

By keeping the historical and moral imperatives of narratives at bay, On Another Note draws attention to the textiles, the clothes, the stories, the places of life, and the wishes of the women in her life, rather than to the roles in which a narrative can place them. There are no heroes or villains, or moral arcs. Their symbolic meanings are personal, opaque, and open-ended.

Both Huda Takriti and Ana de Almeida honor the vernacular archive, but they resist instrumentalizing it. Playing with family photographs’ cadences of gaps and fullnesses, they hold moments of crisis accountable, without judgment and without resolution. Neither claims an exhaustive grasp of the events and moments pictured in their family albums. To the contrary, their eyes are trained on the things that the pictures cannot definitively provide. Their artwork opens the ostensibly “self-evident” imagery of the photograph to the promises of potential, possibility, and hope.

¹ Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” in “Memory and Counter-Memory,” special issue, Representations 26 (Spring 1989), pp. 7–24, esp. p. 7.

² Albrecht Koschorke, Fact and Fiction: Elements of a General Theory of Narrative, trans. Joel Golb, vol. 6 of Paradigms (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), p. 45.

Rashmi Viswanathan

Ana de Almeida (b. 1987 in former Czechoslovakia) is an artist from Lisbon (PT), currently living and working in Vienna (AT). She studied at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Lisbon, at the Lahti Art Institute (FI), and also at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where she is currently pursuing her PhD in philosophy with a scholarship from the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Recent shows and projects have been presented at Belvedere 21, Vienna (2023), Kunsthalle Wien (2023), Vienna, CAV – Centre for Visual Arts, Coimbra (PT, 2022), and Ústí nad Labem House of Arts (CZ, 2021), to name a few. Ana de Almeida was awarded the Austrian State Grant for Media Arts in 2021 and the BES Revelação Art Prize of the Serralves Foundation for Contemporary Art in 2011.

Huda Takriti (b. 1990 in Syria) is an artist and a researcher based in Vienna (AT). She studied at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus (SY) and at the TransArts department at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. Currently, she is pursuing her doctorate in the PhD in Practice program at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Her latest exhibitions include: Kunstraum Lakeside, Klagenfurt (AT. 2024), Galerie Crone, Vienna (2023), Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna (2020), Afro-Asiatisches Institut Graz (AT, 2017), mumok, Vienna (2022), among others. Most recently, she was awarded the Vordemberge-Gildewart Award (2022), the Kunsthalle Wien Prize (2020), and the Camargo Foundation Fellowship (2023).

Huda Takriti’s work was developed in collaboration with

Kunstraum Lakeside

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.