Press information

Joachim Koester

The Ghost Shop

Infos

Preview & Camera Austria International No. 125

Presentation and artists’ talks on occasion of the anniversary issue with Seiichi Furuya, Joachim Koester a.o.

13.3.2014, 6 pm

Opening

14.3.2014, 8 pm

within the scope of CMRK

Curators talk

15.5.2014, 8 pm

Duration

15.3. – 25.5.2014

Opening hours

Tuesday – Sunday: 10:00 – 17:00

One Thursday each month the exhibition stays open until 9 pm

20. 3. 2014

10. 4. 2014

15. 5. 2014

Press downloads

Press Information

Since the highly symbolic year 1989, the Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography by the City of Graz has been conferred biennially on an artist who has published an outstanding contribution in the magazine Camera Austria International. In 2013, the international jury extended this honour to the Danish artist Joachim Koester.

The first collaboration between the artist and Camera Austria goes back to 2006, when Koester participated in the exhibition project “First the artist defines meaning”, and three years later in the follow-up exhibition “Then the work takes place”. Both shows revolved around conceptual positions in contemporary photography that are for instance characterised by a specific approach to organising relations between visibility and knowledge.

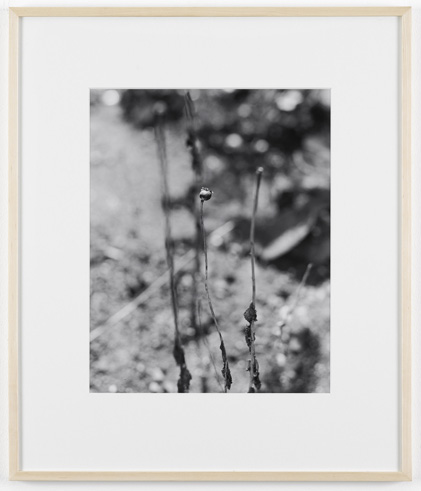

The work of Joachim Koester may also be characterised by citing this relationship, for in his various projects of recent years we repeatedly find a renewed exploration of neglected, almost forgotten events or historical contexts from the history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Obscure, irrational, subconscious, or suppressed aspects of the modern—its “dark” side, so to speak, including spiritualism, occultism, drugs, and failed projects—often figure in Koester’s artwork. Yet we are not only dealing with the act of making visible this other side of modernity; the idea is to also comprehend it as being entwined in the logic of modernism itself, and to situate it in relation to knowledge and to the visibility of modernism.

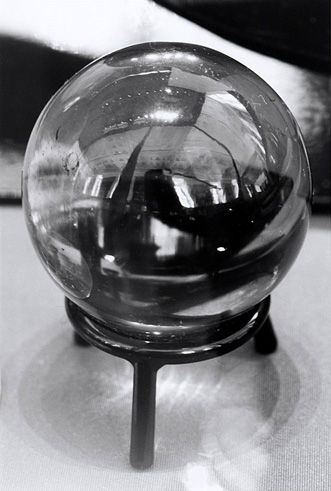

This is very aptly demonstrated in works like “Of Spirits and Empty Spaces”, a 16mm film from the year 2012. John Murray Spear (1804–87), a nineteenth-century socialist and spiritualist, conducted a number of seances in New York in 1861 with the aim of using trance-like dance in a small group setting to receive messages containing ideas for the invention/construction of a new sewing machine. The most popular sewing machine of that era had been created by Elias Howe, who also held a number of key patents, a circumstance that elevated the production costs of all other machines accordingly. The hope was to circumvent these patents and discover a totally new concept that could serve to facilitate the development of a less expensive sewing machine. Spear was convinced that the design of such a machine already existed in immaterial form—in the realm of spirits—and that it would be possible to obtain access thereto. He felt that the new—and cheap—sewing machine would finally provide the women of that era with a means of earning money and thus liberating themselves from the dominance of patriarchal society.

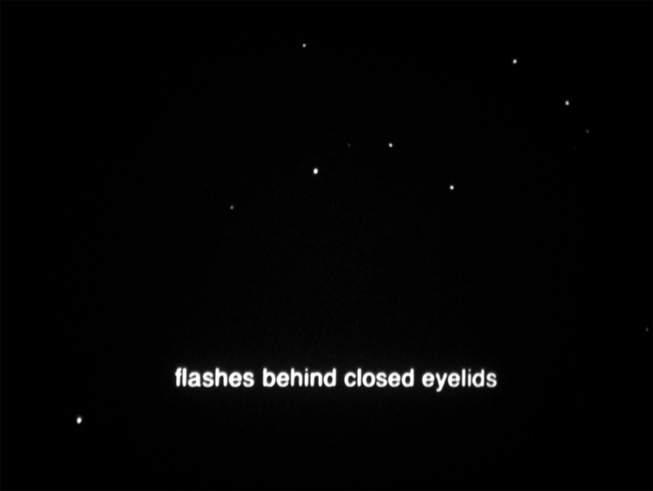

No pictures exist of these seances; featuring instead in Joachim Koester’s 16mm film are exposed dust particles that dance across the screen as white specks, superimposed with text fragments from a description written by Spear. To begin with, the film highlights a “blind spot” of history and knowledge, but also of perception and experience: How might one become immersed in a trance situation without personally succumbing? What might be conceived as representation comes up against its limitations here. The flickering specks of dust in the film also embody the margins of representation. They are the ubiquitous foreign substance that unintentionally accompanies the medium of film and accordingly cannot be removed: an apparition, a semblance of visibility, one that eludes the filmic logic of representation. The narrative about a trance that was meant to pave the way for the production of a machine and deliver a socialist utopia becomes the script of the film. It is via the association of a concept like the “imaginary” that the film—as technical medium—is also linked to Spear’s idea of an (imageless) spiritual netherworld. Yet paradoxically, precisely film is the medium that stands as an example of the industrial production of the imaginary. Like the seances conducted by Spears, film associates the rational production logic and economy of modernity with its—invisible but nevertheless potent—counterpole.

In 2013 the artist produced another 16mm film, one that is likewise entangled in this question of production logic. “HOWE” shows close-up shots of the first sewing machine built by Elias Howe: the translation of the sewing process into a sequence or meshing of the abstracting movements of the machine becomes clear—contrasting with Spears’s anthropomorphic ideas for a design. Indeed, Joachim Koester does not create—metaphorical—images for this modernist invisibility with the intention of making it visible (or describable). He seeks—and invents—pictures that are endemic to this boundary, or ones that spotlight the traces of these histories.

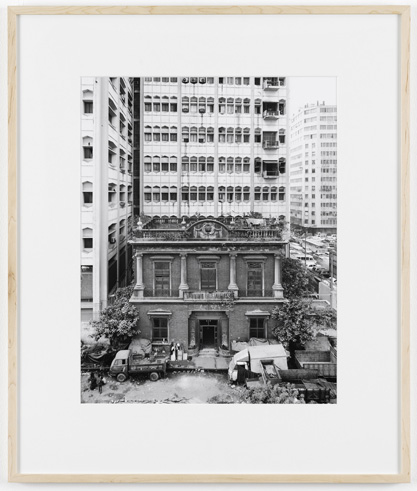

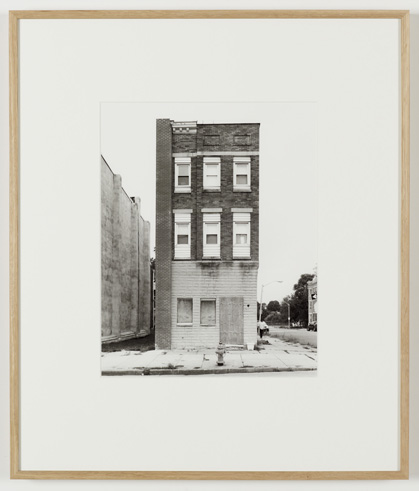

“Nanking Restaurant: Tracing Opium in Calcutta” deals with the pivotal role that the British control of the opium trade played in their economic and political supremacy. This manifested not least in the so-called “Opium Wars” with China in the 1830s, though it is barely mentioned in the official historiography of the “East Indian Company”. The rather “free-floating” research conducted by Joachim Koester during 2005 in Calcutta, the former hub of the opium trade, ultimately led him to one of the last preserved buildings of that era’s China Town: a two-story warehouse that most likely served to store opium and which carries the weathered name “Nanking Restaurant”. The Opium Wars ended in 1841 with the “Nanking Treaty”, which ensured that England maintained control over the trade situation. This coincidence turns the building into a materialised trace of this contested history of trade, captured by Joachim Koester through his photographs of the structure. As such, in this work, too, aspects of modernist production logic—expansion, colonialism, exploitation—are associated with their suppressed histories (which involve both the literary heritage of the drug opium and the fatal consequences of its widespread consumption, namely, the social immiserisation of the masses).

The artist himself speaks of an “invisible index of things” which, though hardly discernible and not part of overt historiography, nevertheless is clearly determinative at its core. Joachim Koester can thus be said to operate at the margins of the documentary, at the boundaries of that which, in its state of visibility, references knowledge or produces knowledge through the act of making visible. His projects—consistently tied to associatively guided research and conveyed through precise pictures and photographic series—therefore field an important question about the possible links between image and narrative: What is being told and what is being shown? What is being neither told nor shown? And for what reasons? “I want the photograph, my documentation, to exist in a field of tension between what is depicted and the narrative content.” The artist thus situates the photographic image in a complicated realm amidst perception, history, knowledge, politics, and visibility. It follows that the work of Joachim Koester represents an enormously significant contribution to our current conception of photography’s role in our society and culture.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.