Symposion on Photography XXI: The Violence of Images

Infos

Symposion on Photography XXI:

The Violence of Images

5.10.2018, 4pm – 8pm

6.10.2018, 2pm – 8pm

(Please find the schedule as PDF at the bottom of the page)

Camera Austria, Graz

By registration only: Angelika Maierhofer exhibitions@camera-austria.at (fully booked, but you can register for the waiting list)

Free Admission

Language: English

A collaboration of Camera Austria and steirischer herbst

Participants:

Christine Frisinghelli

Marina Gržinić

Ana Hoffner

Tom Holert

Jakub Majmurek

Guy Mannes-Abbott

Ines Schaber

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Ala Younis

Moderation: Christian Höller

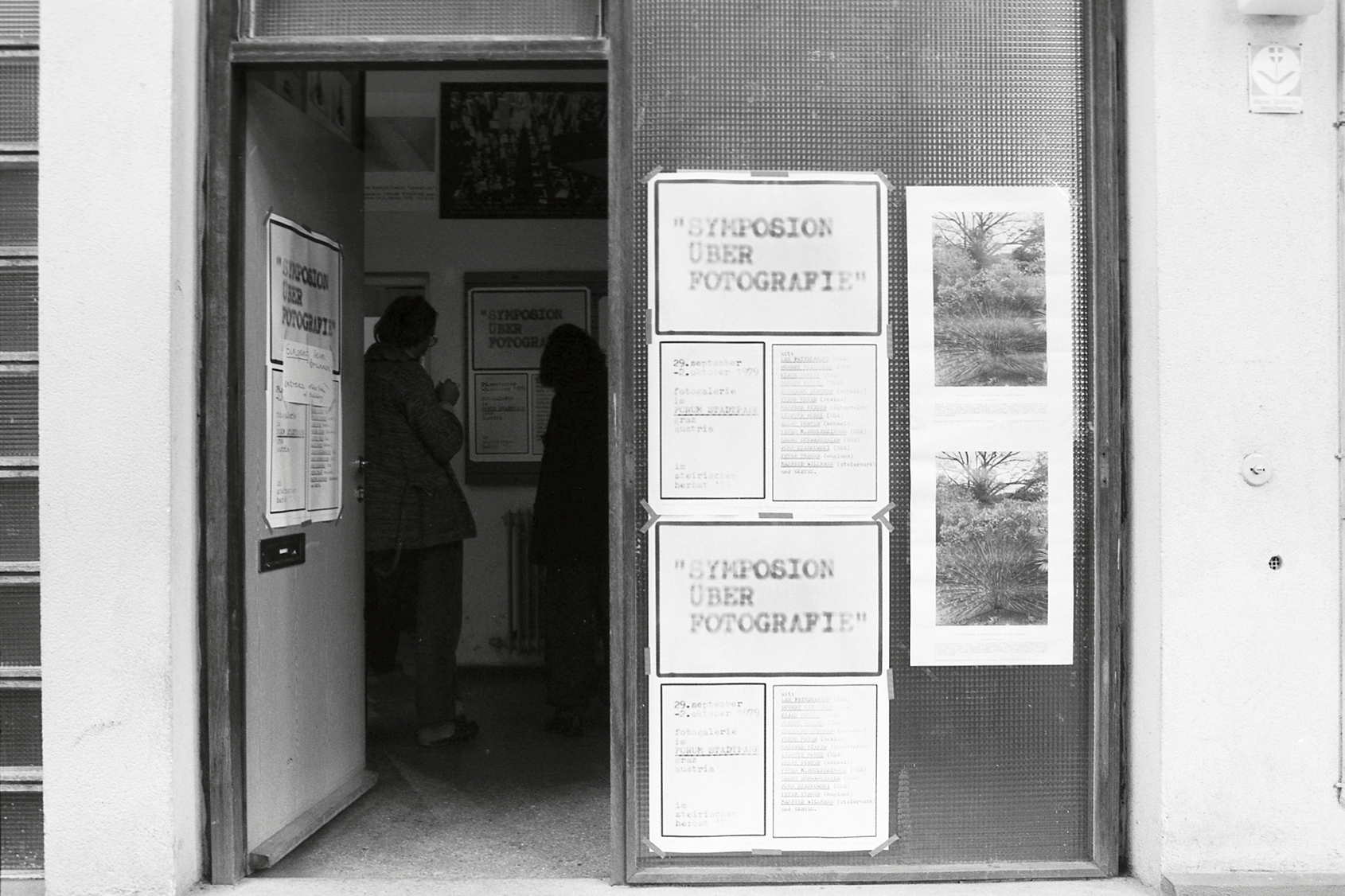

Illustration: Symposion on Photography I, Fotogalerie im Forum Stadtpark, Graz, 1979. Photo: Helmut Tezak.

Intro

Photographic images have long since forfeited their ability to be taken for granted. Repeatedly reappropriated and reapplied, they appear to establish all kinds of things, especially when the truth is no longer the truth, as Rudy Giuliani, former mayor of New York and present attorney of the American president, recently asserted. Does this give them a secondary role and make them proof of arbitrary meaning production? Are they thus subjected to a power that is external to the images? Or does a power of the images itself attend to this power, understood as a form of its violence?

How can this violence be described? Is it connected to the violence shown in countless photographic images, in those ugly images that the present Austrian chancellor already addressed in 2016, stating that they are inevitable? They are meant to confirm the danger arising through immigration, to lend a picture to this very danger, yet precisely for this reason the images tie the involved individuals to a framework, designating this framework of their existence as a no-right-to-existence, stranded along a permanent border that they are never allowed to cross, desubjectivized and devoid of rights. Are they not, in this sense, also images that exert force by assisting a truth of power that is actually a truth of violence?

Perhaps the violence of the images consists in the very fixation and inclusion of visibility and meaning in favor of a truth of power—an inclusion in certain conventions of (political) production of meaning and thus a twofold sense of finishing and locking in meaning that denies or overlays other possible meanings? This would then imply the issue of the violence of the images: how they ascertain things and, in the process, obscure and divide, assign, compartmentalize, inscribe, conclude, how they make things invisible, eliminate them, how they specify a truth that is a truth of violence resisting all other truths.

So how can the disquiet of images be recovered—their resistance, their transient and volatile presence, their ambiguity, their incompleteness and integrability, their contingency? How can the political nature of the images be reconstructed beyond their respective content and meaning in that the images are used to add something to reality that destabilizes and transposes it into an imbalance, into a form of incongruity and disaccord, which might then open up a space for negotiation—how everything might be totally different beyond a truth of power?

We have passed these questions on to a series of experts and artists: their contributions to the Symposion on Photography XXI attempt to once again unlock the inclusive and exclusive framework of these images, so as to locate and rewrite those moments in which a violence of representation emerges and circulates.

Reinhard Braun

Reinhard Braun is artistic director of Camera Austria and publisher of the magazine Camera Austria International since 2011. He lives in Graz (AT).

Christian Höller is editor and copublisher of the magazine springerin – Hefte für Gegenwartskunst. He lives in Vienna (AT).

Christine Frisinghelli: The Symposion on Photography as a Place of Debate

With the Symposia on Photography, held annually between 1979 and 1997 as part of the steirischer herbst festival, continuous discourse and reflection on the functions and mechanisms of photography were fostered (and thus also something like “photo culture” in this country). Such thought also inspires the magazine Camera Austria International, published since 1980 and originating in the context of these symposia. Through international exchange and an exploration of theory, history, and artistic practice, it was possible for controversies, interconnections, and contradictions to be voiced in this context. Yet again and again it was the critical artistic practice in particular that challenged and changed our perspective—as I would like to illustrate by citing several select positions from the history of the symposia: Mao Ishikawa, Susan Meiselas, and Jo Spence. Three woman photographers—in my eyes, exemplary—who in their work on and with the photographic image entrust us with the task of reflecting on the limits of the defined genre of photography (from the family album to war reporting)—and who have succeeded in transcending these limits through a full devotion to the subject of their work.

Christine Frisinghelli is a co-founder of Camera Austria and the magazine Camera Austria International. She lives in Graz (AT).

Marina Gržinić: Images of Violence, or the Violence of Neoliberal Necrocapitalism

Images with violent content are always historical, as what is seen as violent is constructed and is violently managed; therefore nothing is natural in relation to violence. What will be defined as violent is always an outcome of violent hegemonic processes. Seeing images of killings can provoke our rebellion and our insurgencies, unless we are paralyzed by our normativized occidental lives. Europe and the global neoliberal capitalist system in general are well attuned to the hierarchization, control, and management processes of the present neoliberal capitalist states. Especially under attack are migrants and all those not considered to be “natural” parts of the neoliberal capitalist national body in the West: asylum-seekers and refugees escaping war-torn parts of the global world (the Middle East, Africa), from conflicts induced by capital and imperial management. On the other side and at the same time, we can see, for example, the last election campaign in Austria, with posters by the Freedom Party (FPÖ) containing blatantly racist and fascist slogans and images. My interest is to connect racism with visual narratives, “trophy” artifacts, and culture. I will look at racism from a historical perspective, showing a horrifying trajectory of structural racism that reproduces itself almost always circularly from a pseudoscientific (biological) racism, “progressing” toward “cultural racism” to “return” again to °“scientific racism,” though then coined “intellectual racism.”

Marina Gržinić is an artist and teaches at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (AT). She lives in Ljubljana (SI) and Vienna.

Tom Holert: Valences of Visual Violence

Speaking of the violence performed by images is indicative of a shift in the conceptualization of visuality. Having been told how images are bestowed with (and exert) power—the power to affect, to entail beliefs and actions—addressing the violence of images seems to call for a slightly different set of critical tools. Walter Benjamin’s 1922 essay “Zur Kritik der Gewalt,” as Jacques Derrida noted, has been misleadingly translated as “Critique of Violence,” thus downplaying that Gewalt in German includes at least two meanings: legitimate power of the law on the one hand and violence as brute, illegitimate, material force on the other. Among the other registers in this complex typology is the “violence of abstraction” (Derek Sayer), that is, the structural force engendered by the capitalist value form, which again develops its full analytic momentum only when being put in relation to feminist and decolonial notions of violence. Considering such conceptual intricacies, how do images critically inflect or diffract the knowledge and experience of violence (if they do)? The talk will address this question by way of a reassessment of those terms by which images are conceived as being essentially performative. Does performativity still yield theoretical surplus? Pondering the political potential of the “question of non-performativity” (Sarah Jane Cervenak) may prove helpful in effectively recalibrating the notion of “Gewalt der Bilder.”

Tom Holert is an art historian and cultural critic who recently curated the exhibition “Neolithic Childhood. Art in a False Present, c. 1930” at HKW, Berlin (DE), together with Anselm Franke. He lives in Berlin.

Ana Teixeira Pinto: Paint It White!

Geopolitically speaking, the present moment could be defined as a process of de-Westernization: amidst the ongoing dispute over control of the colonial extraction matrix, the West is rapidly losing its position of dominance. As social rights wither, a massive security apparatus was put in place in Europe and the US to “manage the supposed civilisational threats to the nation” (Chris Chen, “The Limit Point of Capitalist Equality”). Under the banner of the “War on Terror,” the policing of racialized lives at home converges with the renewed intensity of colonial violence abroad, instituting a structure of affect that leads those who are hurt economically to invest themselves nonetheless—libidinally and symbolically. Whiteness, one could say, functions as the allegorical glue that holds a wealth of contradictions together. This, I would argue, points to a new configuration of fascist ideology taking shape under the aegis of, and working in tandem with, neoliberal governance.

Ana Teixeira Pinto is a writer and cultural theorist who teaches at the Berlin University of the Arts (DE). She lives in Berlin.

Ines Schaber: Who owns an image?

The archive fever that has run rampant since the publication of Derrida’s famous book has produced many adaptations and continuations. Questions like “Who houses and watches over the archive?” or “Who controls what is collected and made accessible?” and “Who writes history through the control of the documents?” provoke renewed discourse about the archive and the question of how we today (want to) write, read, and discuss history. In my artistic practice, these questions play a vital role. In the project “Unnamed Series,” realized in collaboration with the artist Stefan Pente, these questions were posed in a very concrete way. It referenced the photographs that Aby Warburg took in the late nineteenth century on his journey to visit the Hopi Tribe. Warburg himself never wanted the pictures to be published, yet one hundred years later they appeared in a book of photographs. In my talk, I will discuss the challenges and issues arising through dealings with the archive to which these images belong, and with the photographs themselves: What does it mean to publish photos that were not earmarked for the public gaze? What does it mean to own pictures? Is owning pictures a right or a responsibility? What conclusions might we draw today in relation to the collecting of images which represent individuals who have a different relationship to Western concepts of ownership and representation?

Ines Schaber is an artist and teaches at the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia (US). She lives in Los Angeles (US) and Berlin (DE).

Guy Mannes-Abbott: Any Place for a Nonviolent Image?

Entangled within representations of violence or the violence of representation, and the totalizing of the visual/abject lure of virtual reality, is the anomalous question: How to think a nonviolent image? I will proceed with story, speculation, and seven images to test exceptions like: Why would I not have images of state-sponsored massacres of “Muslims” in Gujarat in 2002 despite witnessing them directly? Or: What of the banality of violence in my images of being deported as a “security threat” (or, writer!) at Dubai International Airport in 2017? I’ll pick up “the mental event of taking a picture,” Lotringer’s description of Baudrillard’s photography, to focus on the “taking place” of images. I’ll look at contemporary nonrepresentational photographic art images that evade the issue of nonviolence. Then I’ll use a measure from “without” European intellectual histories to speculate about what a nonviolent image could be, constitutively and formally, before we are all “obliterated.”

Guy Mannes-Abbott is a writer, essayist, and critic. He lives in London (GB).

Jakub Majmurek: Immediacy and Representation: New Social Movements of the 2010s and Related Photography

In 2011, TIME magazine chose “the protester” as its person of the year. 2011 had indeed been a year of protest. Social movements such as the Arab Spring in North Africa, Indignados in Spain, and Occupy Wall Street in the US took the streets and squares of cities all around the globe. The images of protest politically defined the new decade in the same way as the images of 9/11 had politically defined the previous decade as the time of “War on Terror.” After 2011, other waves of protests followed—from Black Lives Matter in the US to Black Protests in Poland (against attempts to completely ban abortion). All of these movements seem to share certain assumptions about politics. They were organized horizontally, displaying distance or even distrust toward such established political entities as political parties. And all purposely decided to abstain from electoral politics and the attempts to capture the existing structures of power. In my presentation, I will investigate how the problems of immediacy and fear of representation express themselves in the photography accompanying the new social movements of the last decade, focusing on the following issues: the resistance of the new social movements to be defined by the single, iconic image; the rise of “civic journalism” and “civic photography” accompanying new social movements; and the role of social media as the new space of circulation of political images. In the end, I’d like to ask the question: How can photography become political in all the circumstances described above?

Jakub Majmurek is a philosopher, film expert, and political columnist. He lives in Warsaw (PL).

Ala Younis: A Decomposition of Violent Images That We Are In

In one of many introductions that he continues to add as prefaces to his first novel, That Smell, Sonallah Ibrahim responds to the literary criticism of his descriptions of events, that is, the images that are imagined through reading his words were too violent. Sonallah published his novel following a five-year confinement in a political prison in Egypt because he was a communist. In the early years of his imprisonment, the leader of the Egyptian communist party passed away under torture in the same prison, while his torture was witnessed or also experienced by other inmates. In this introduction from 1986, Sonallah recalls the times in which he authored his lines, and the brutality of the images he had seen in prison upon which he could not elaborate with a less violent composition of scenes. As his book was banned just after it was printed in 1966, and later when his nation went through the defeat of 1967 war, he also questioned himself on whether his texts were doing harm to his own country as were these prison experiences. In 2018, I met Sonallah in person in Cairo. I was working on his books in parallel to a compilation of a monograph for the displaced Palestinian artist Abdul Hay Mosallam, who was a technician in the Jordanian army and later in Fatah’s army loaned to the Libyan air force, before he became an artist at the age of thirty-nine. Abdul Hay’s works reflect a yearning for the life of the freedom fighter that he always wanted to be. I was attempting a rereading of his depictions of rifles combined with roses near bodies of men and women sacrificed in the liberation struggle. Through these literary and art examples, this presentation is on our composition and decomposition of violent images, when we are inside these images ourselves.

Ala Younis is an artist and co-founder of the publication platform Kayfa ta. She lives in Amman (JO).

Ana Hoffner: Nonaligned Extinctions: Slavery, Neo-Orientalism, and Queerness

The figure of “bacha posh,” which means “dressed like a boy” in Dari, currently receives central attention in the vocabularies of resistance to terrorism. The term is used to identify girls who grow up as boys in Afghan society and play the role of a son for their families for a limited amount of time before puberty. “Bacha posh” have existed independent of the Western gaze for a long time, but they have made their way to the channels of mainstream information distribution only recently. More than anything else, “bacha posh” has quickly turned into a phenomenon produced by an increasing body of reports, documentaries, and images. In this lecture, I will try to trace back the conditions of readability of non-European childhood and sexuality in the present, which underlie the various interpretations of “bacha posh” as a cultural practice from elsewhere, and their infliction in persisting fantasies of the queer child and the fugitive slave.

Ana Hoffner is engaged in an art practice that reworks moments of crisis and conflict in recent history. Her book The Queerness of Memory has been published this year at b_books Berlin.