Camera Austria International

67 | 1999

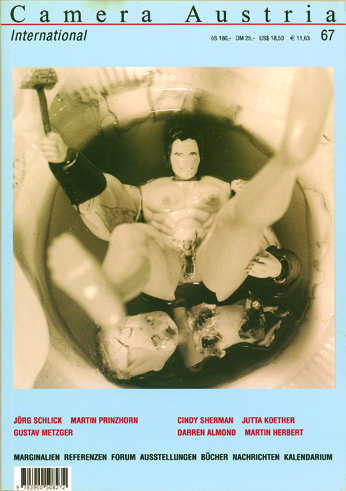

- MARTIN PRINZHORN

Some preliminaries on aspects of cognitive psychology in the works of Jörg Schlick - JÖRG SCHLICK

- JUTTA KOETHER

Cindy Sherman: Old Witnesses - CINDY SHERMAN

- GUSTAV METZGER

Killing fields: Sketch for an exhibition - MARTIN HERBERT

Darren Almond - DARREN ALMOND

- ROLF SACHSSE

Marginalien zur Fotografie

- WOLFGANG VOLLMER

Referenzen

Preface

While preparing our last issue, CAMERA AUSTRIA No. 66, which was dubbed “Scene of the Crime” and included an essay by Diedrich Diederichsen that focused on the question of political memory through photographs, we came across the recent work of Gustav Metzger (born 1926). Known in the Sixties for his manifestos and “lecture-demonstrations” of his auto-creative and auto-destructive art (ADA), Metzger’s political involvement and uncompromising criticism of the art business led him, in 1977, to call for an “art strike.” In the end, however, he was perhaps the only one to set aside artistic production in favor of reflection and theoretical activity.

Metzger’s currently increasing presence is the result not only of the advancing art-historical reappraisal of artistic manifestations of the Sixties, but also of his turn to a new field of artistic involvement: his “Historic Photographs” series. Here he dedicates himself to pictures that deal directly with 20th century political history, from documentary photography of the time of National Socialism, to war within and over Israel, terrorist bombings, and recent events in former Yugoslavia; images of horror, the peaks of destruction and chaos.

Metzger has agreed to the publication, in this issue, of a previously unpublished manuscript – the first draft of “Historic Photographs”, which he originally intended to put on show bearing the title “Killing Fields.” His conceptual reasoning is made clear in the text. He strives to reshape the form of exhibition and artistic work; to recreate the possibility of artistic communication of historic events, the perception of which the mass publication of press photography has virtually made impossible. The realization of this concept in diverse installations shows views of the “Historic Photographs” at the Spacex Gallery in Exeter, the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Kunstraum München, the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, and the Kunsthalle Nürnberg, which all serve to illustrate Metzger’s text. Icons of press photography are initially removed and concealed in sculptural works – contextually related to the event depicted – by “covers”, some of which to be revealed by the viewers. The sphere of experience that emerges from the exhibit provides the means for a new approach to these photographs that comes with uncertainty for the viewer, but also a delay in perception that makes it possible to reflect on the history of a violence-laden century.

Manfred Willmann, Marie Röbl, Maren Lübbke

September 1999

Entries

Forum

GÖTZ DIERGARTEN

BETTINA HOFFMANN

NICOLA MEITZNER

KAI KUSS

KATHARINA BOSSE

RUTH KAASERER

NINA SCHMITZ

Exhibitions

Notorious. Alfred Hitchcock and Contemporary Art

Museum of Modern Art, Oxford; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

Hellen van Meene

The Photographer’s Gallery, London

JOHN TOZER

EXTRAetORDINAIRE

Le Printemps de Cahors, Cahors

JULIA GARIMORTH

Mistral in Arles. Recontres International de la Photographie

Arles

BRUNO CARL

La Biennale di Venezia: Dapertutto

Venedig, Arsenale (Castello Giardini, Corderie, Gaggiandre, Artiglierie, Tese)

SABINE B. VOGEL

Video CULT/URES. Multimediale Installationen

ZKM, Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Museum für neue Kunst, Karlsruhe

MATTHIAS MICHALKA

Mehrwert / “Do You Really Want It That Much?” – “…More!” von Volker Eichelmann, Jonathan Faiers und Roland Rust

Ursula Blickle Stiftung, Kraichtal

VERENA KUNI

Connected Cities. Kunstprozesse im urbanen Netz

Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg

CHRISTINE KARALLUS

Puppen Körper Automaten

Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf

Heaven

Kunsthalle Düsseldorf

MAGDALENA KRÖNER

Selbstbilder der Materie

Museum Wiesbaden

WOLFGANG VOLLMER

Stephen Shore / Candida Höfer

Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln

WOLFGANG VOLLMER

Young. Neue Fotografie in der Schweizer Kunst

Fotomuseum Winterthur

RUTH MAURER

Martha Rosler. Positionen in der Lebenswelt

Generali Foundation, Wien

SIGRID ADORF

Inge Morath

Kunsthalle Wien im Museumsquartier, Wien

MARIE RÖBL

Die Farben Schwarz

Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz

CHRISTOPH GURK

Books

Das andere Denken des Aussen. Zu Philippe Dubois’ “Der fotografische Akt”

Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1999

MICHAEL WETZEL

Junggesellinnen. Zu Rosalind Krauss’ neuem Buch “Bachelors”

MIT Press, Cambridge / Mass, London 1999

STEFAN NEUNER

Ulf Erdmann Ziegler: Fotografische Werke

DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1999

MAGDALENA KRÖNER

Baudrillard als Fotograf. Ein Plädoyer für die Macht der Verführung und der Illusion

Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 1998

KERSTIN BRAUN

Malick Sidibé

Scalo Verlag, Zürich 1998

Max Penson

Wave Collection PBK, Köln 1999

Philip-Lorca Dicorcia: Street Work

Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca 1998

JUDITH SCHWENDTNER

Imprint

Publisher: Manfred Willmann. Owner: Verein CAMERA AUSTRIA, Labor für Fotografie und Theorie

Sparkassenplatz 2, A-8010 Graz

Editors: Christine Frisinghelli

Editorial assistats: Maren Lübbke, Marie Röbl

Translations: Bärbel Fink, Warren Rosenzweig, Jörg von Stein, Richard Watts