Press information

Peggy Buth

Vom Nutzen der Angst – The Politics of Selection

Infos

Press preview

13.9.2019, 11 am

Opening

13.9.2019, 7 pm

Duration

14.9.–17.11.2019

Opening hours

Tue – Sun, 10 am to 5 pm

Curated by

Reinhard Braun

Press downloads

Press Information

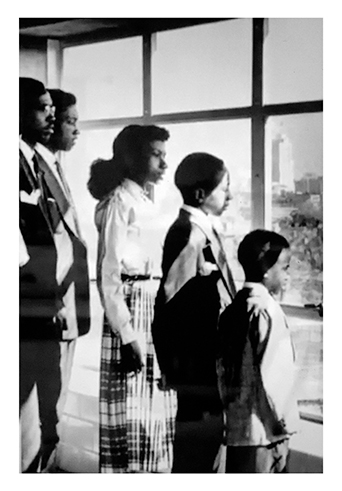

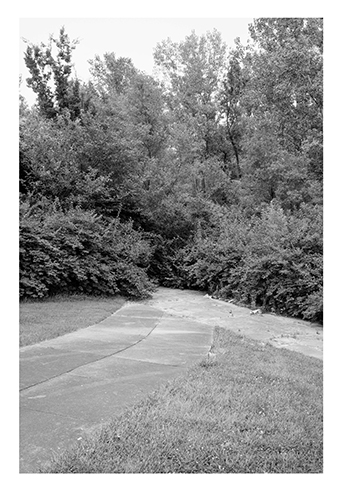

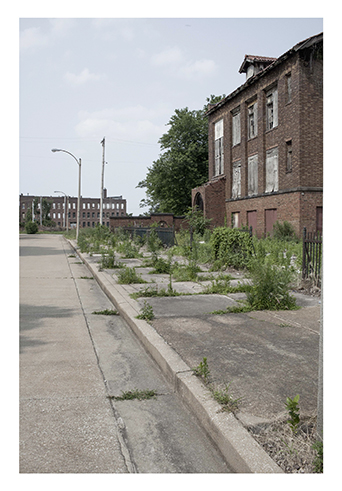

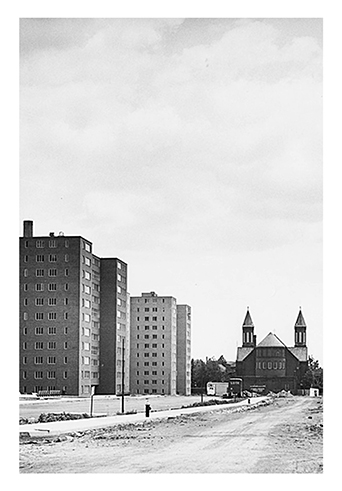

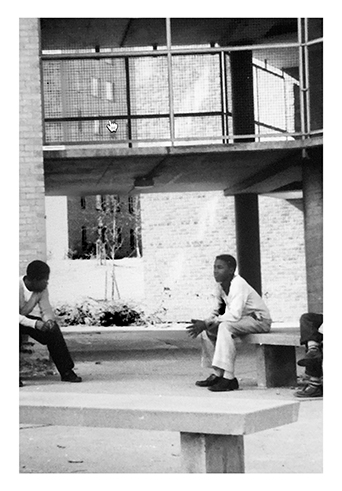

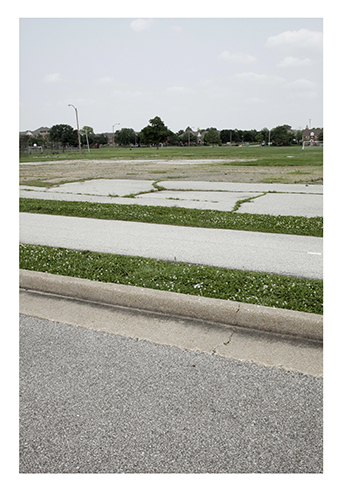

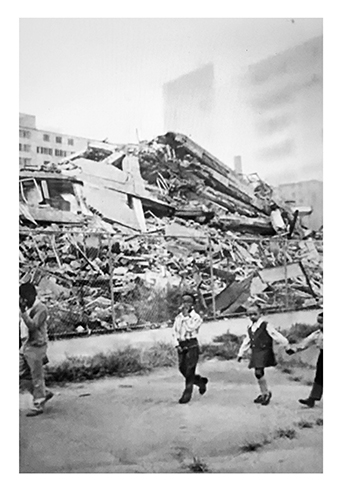

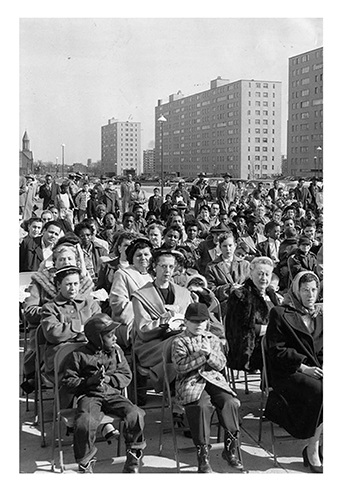

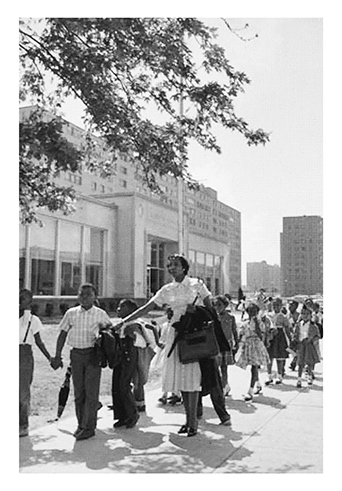

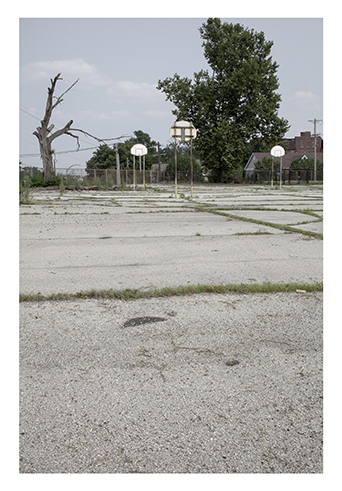

In the three-minute black-and-white video “Pruitt-Igoe Fallow Area” by Peggy Buth from the year 2015, the viewer follows the camera through a wasteland, through an overgrown forest, in which debris from former buildings appears again and again. The video was created in connection with the artist’s research on the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in the northern part of St. Louis, Missouri. It was originally planned by architect Minoru Yamasaki (who also designed the World Trade Center) as a model residential complex in the scope of an already weak social housing landscape in the United States. Residents started moving into the thirty-three eleven-story buildings in 1954, and in 1972 they were already demolished under the spotlight of media and political spheres—a momentous date from an architectural and urban-planning perspective, which for Charles Jencks signified the end of postwar modernism. Originally the individual buildings were to offer housing segregated according to race, but a Supreme Court ruling in 1954, shortly before construction was completed, ruled this intention to be unlawful—which resulted in the white residents moving out of Pruitt-Igoe within a two-year period. Since no funding for maintenance of the infrastructure was made available, the remaining residents engaged in a rent strike lasting nine months.

For postwar modernism, this housing project thus has twofold symbolic character: first, for the political utopias aiming to combat poverty, attain equality, ensure civil rights, and overcome racial segregation; and second, for the purported failure of these political and social aspirations. Peggy Buth thus literally passes through the ruins of modernity for her video “Pruitt-Igoe Fallow Area,” in a wasteland between nature and city which appears to be populated by the specters of this modernity. Nothing ended up being built in place of the Pruitt-Igoe complex; it was not replaced by another urban-development concept, but rather made to disappear, though not completely. The wasteland in “Pruitt-Igoe Fallow Area” is just as symbolic: it covers an end without a new beginning, concealing and overgrowing an act of failure marked by reasons that have not been analyzed, offering only the welcome opportunity to reduce social expenditures and introduce a penal strategy of zero tolerance.

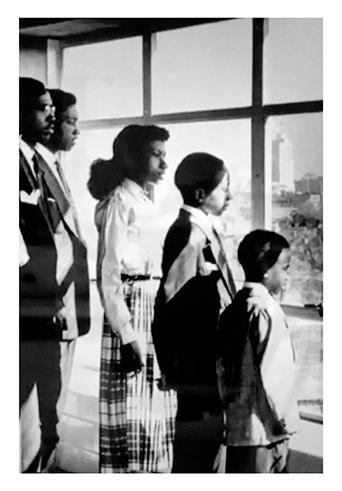

“If you live on or near one of the nearly 900 streets in the U.S. named after Martin Luther King, Jr., you’re more likely to be poor, and you’re more likely to be black. And some might argue that your street serves more as a symbol of inequality than of progress made since King’s death” (Adele Peters). Peggy Buth did not limit her research in the St. Louis area to Pruitt-Igoe. She also took pictures in Kinloch, a small town that borders on St. Louis and Ferguson and was at one point home to the oldest black community in Missouri. In 1950, Kinloch had a population of around 6,000, while in 2012 only 300 people remained. Due to the construction of St. Louis Lambert International Airport in the 1990s, Kinloch lost 80 percent of its residents. It was in Kinloch that Buth found the street sign of a Martin Luther King Boulevard, on the corner of Fifth Street. The sign also seems to be situated in a fallow area of sorts, assuming a crooked position and situated next to garbage, an old tire, and concrete blocks that restrict access to Fifth Street. The urban decline evident along the many Martin Luther King Boulevards is a nationwide phenomenon in the US, from Houston to Milwaukee to Washington, DC. In most cities, these boulevards are among the most dangerous streets, shaped by gang crime, drug dealing, and car theft. The average school dropout age for youth living on streets of this appellation is thirteen. A street name that is inseparably linked to the civil rights movement—and that lent expression to the black population’s hope to be part of social prosperity, and also hope to be able to participate in political life in the United States—today attests to the demise of these very hopes. In fact, it spotlights a lingering segregation of American society motivated by social and racist issues.

With the series of photographs on the Martin Luther King Boulevards Peggy Buth in turn finds herself in a kind of ruins, the ruins of society. The specters prowling around there are not only of neoliberal or postdemocratic nature, but are also the fairly living ghosts of racism, or perhaps rather the racist undead. Peggy Buth, in her works, touches a sore spot related to capital and race; she orbits this wound, keeping it open in order to counter the staggering rhetorics of postmodern discussions asserting that all of this is long since history. All of these projects, and countless others (some of which are yet to be mentioned in this text), concentrate on a manner of archaeology of squandered political and social chances to have facilitated a different present. And for Buth it is not enough to slave away at exploring the present. She sees in everything the historical dimension, the longue durée, as historian Fernand Braudel termed it, all of which were necessary for shifting structures within society; or the long staying power, the exceedingly broad temporal scope of ideologies, convictions, and cultural constructions which—perhaps in altered form, updated, instagramized—still impact present-day political, social, and cultural paradigms, convictions that we thought to have long since overcome.

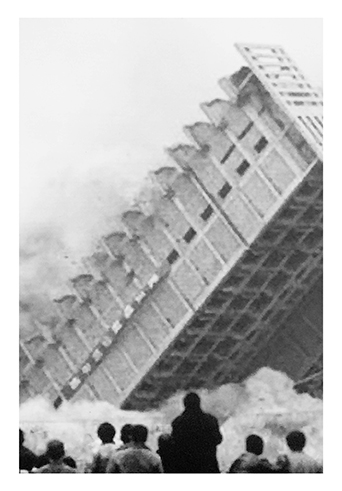

Perhaps these are the specters being pursued by Peggy Buth. They can hardly be shown instantaneously or be represented directly, or even forced into an image that could document their presence in the present day. Instead, they must be reconstructed, assembled, and—even more importantly—they must have rendered an experience. Buth does not deliver critical visual essays with a statement; her series are reports on a sojourn, on exploration, during which the artist posits herself in relation to the place in question, thus probing her own role and bringing into play her own agency. The images belong to this report on a sojourn, a journey, a visit, and a pacing that may well be accompanied by the aforementioned ghosts. They also nestle into the associations arising within the viewers; they are ephemeral and almost transparent, yet they are also the explosive charges that bring down numerous modern housing complexes and architectural ensembles in the video “Demolition Flats” (2014). We are not speaking here of otherworldly specters but are rather spotlighting the phantoms of our present, their irritating and persistent presence that engenders an absence in the regimes of visual phenomena and invites us to forget the conflicts, schisms, wars, suffering, and the dysfunctional circumstances of our life which provide the impetus for global neoliberal capitalism (T. J. Demos).

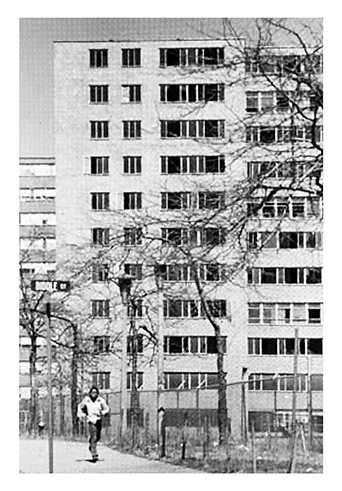

So how do urban planning, economics, racism, and their representations interrelate in relation to such phantoms? From which utopias have “our” Western societies at least bid adieu? And how can this political change be read and understood up close in urban landscapes? Which acts of resistance have been wielded against these processes of disintegration? And are there still societal powers that are trying to keep the question of another order on the political agenda? Buth has been exploring these questions since 2013 at the latest, when she began taking photographs and conducting research in the northern suburbs of Paris like La Courneuve, one of the starting points of unrest in Paris during the year 2005. In the slide projection “91, 92, 93, 94 / 75” (2017), Buth shows her shots from the Paris banlieues together with found and archival material displaying colonial traces of French history. The Départements 91 to 94, as well as today’s Département 75, which encompasses downtown Paris, were created as part of the restructuring of the former (more comprehensive) Département Seine, which by the 1960s had become too large and complex for sensible administration. Through Algeria’s independence in 1962, the current Département figures were made available, since they had originally denoted territories in Algeria like Algier, Oran, Constantine, and the Territoires du Sud. These new Départements around Paris had harbored countless migrants from the Maghreb states and the sub-Saharan region since the postwar period. Extensive housing projects, the aftermath of deindustrialization, and the disintegration of the social welfare state transformed these peripheral urban areas into increasingly impoverished residential and dormitory districts with underdeveloped infrastructure, reduced work opportunities, and poor transport to the city center, which is moreover isolated from such urban areas by the Boulevard périphérique de Paris.

France’s colonial past has become inscribed in the layout of Paris, with the city center and the periphery mapping out social and ethnically defined hierarchies, which are, in turn, inscribed in the life of the residents. The spatial organization of the city enables an organization of identities, an incessant production of the “Others” and their distribution. In “91, 92, 93, 94 / 75,” Buth traces stereotypical representations and highlights contradictions between official rhetoric and concrete urban environments, between the messages disseminated by newspaper articles—“Le ras-le-bol,” those who are fed up, or “Do away with Sarkozy’s methods”—and pictures of—unemployed? bored?—youth in parks. Arising here is a sequence of photographs that is full of contradictions, in terms of both their aesthetics and their “themes.” The artist also confronts us with our own prejudices and insecurities in interpreting these images. To what extent are we ourselves already biased by our situated knowledge? What is our stance, and in which social space are we standing when looking at this conflicting imagery? From which social space is our knowledge about these other social spaces organized and determined?

Peggy Buth presents all of these works under the title “Vom Nutzen der Angst – The Politics of Selection.” Indeed, the purported decline of large sections of contemporary cities happens not due to social automatisms, but due to political and economic decisions: politics of selection and election, politics of distribution and redistribution, of the production of “superfluous populations,” as Zygmunt Bauman has termed it. In his book In Search of Politics (1999), he notes: “the only communities which the loners may hope to build and the managers of public space can seriously and responsibly offer are ones constructed of fear, suspicion and hate.” It has become commonplace in the context of political language to warn against mechanisms of division. Yet they are not only mechanisms of language, but also mechanisms of architecture and urban organization (and perhaps this division has already long since reached the images themselves). In some of Peggy Buth’s photographs, this division and cleavage seem to be rendered more blatantly: in the basic neglect of the streets, in the fences and the desolateness, in the potholes and the missing roofs, in the closed community centers, the steps overgrown with grass, and the rubble of demolished buildings. Yet the division and disintegration extend much deeper, surpassing anything that pictures can show. It is not primarily visual, but rather material in a more comprehensive sense, organizing and disorganizing the things and the people, the bodies and the languages. Under these—post-documentary—conditions, how might the meaning of solidarity and empathy, the meaning of the history and the memory of emancipatory movements and self-empowerment, be perpetuated, and how might their diffusion in the course of (de)industrialization and globalization be countered? How can the idea of a utopia be recaptured?

Reinhard Braun

Peggy Buth studied photography and Visual Arts at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig (DE) where she graduated 2002, 2003–05 she was a fellow at the Jan van Eyck Academie Maastricht (NL). Since 2016 she is professor for media art at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig. Her works have been shown in numerous exhibitions, i.e. at Exhibition Research Centre, John Moores University, Liverpool (GB); Parc Saint Léger –

Centre d’art contemporain, Pougues-les-Eaux (FR); Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart (DE); CAC Vilnius (LT); Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt am Main (DE); K21, Düsseldorf (DE); Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover (DE); Bétonsalon, Paris (FR); La Synagogue de Delme, Delme (FR); Brussels Biennial (BE) and recently at Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin. Buth received numerious scholarships and awards in Germany, the US, France, and Belgium. 2014 she received the “Contemporary German Photography” Grant donated by the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung with a subsequent solo exhibition at Museum Folkwang, Essen (DE). In 2018 she was nominated for the Deutsche Börse Foundation Photography Prize 2019.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.