Press information

Stephan Keppel

Hard Copies

Infos

Press preview

11.6.2021, 11 am

Opening

11.6.2021, 6 pm

Duration

12.6. – 15.8.2021

Opening hours

Tue – Sun and bank holidays

10 am – 6 pm

Curated by

Taco Hidde Bakker

Press downloads

Press Information

Cities of Thrift and Ink

by Taco Hidde Bakker

The wear and tear of the city renders it humane. The wear resonates well in “misprints” spit out from wear-sensitive printers.

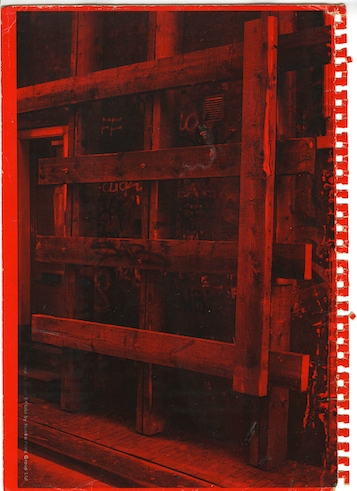

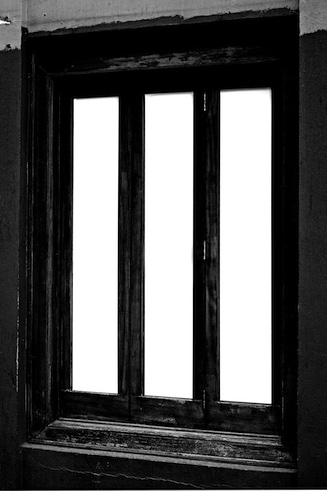

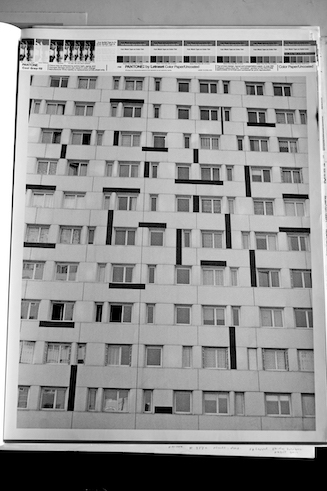

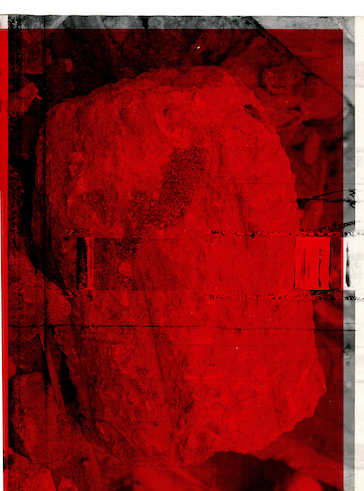

Dutch artist Stephan Keppel’s four photo/graphic city books attest to an incisive exploration of the relations between the built environment, the image, and the book. In Keppel’s books and spatial presentations, there is an entanglement of the material appearance of (things in) cities, ways of picture-making, the arrangement of images, and found objects. Boiled down to its essence, his work seems to be about patterns and rhythms and cycles. The working process of his books published so far swings between cycles of taking photographs, appropriating image files, printing the files using (often discarded) printers, rescanning, and reprinting. This results in idiosyncratic, oftentimes abstracted images with material qualities that are interwoven with the material surfaces of the built world to which these images also refer. There arises visual tension between the image as image and the image as a window onto something beyond its own. Nothing in Keppel’s books reminds me of any conventional photographically illustrated book about cities.

From my childhood, I remember a book on my parents’ bookshelves in the living room, a book on New York City from a generic series of affordable books about world cities. The volume was stuffed with what I would now deem mediocre photographs. The cover carried a blue-skied image of the Twin Towers, drawn sharp against the clear sky. This became a first reference point for the long-distance photographic look of cities that I had never been to myself. Was this what a really big city looked like? I remember seeing endless many-eyed walls lining streets as straight as a Dutch canal, and an occasional skyscraper piercing the cloudless skies. I first learned the word “skyline.”

London became the first major city I ever visited. It was right before unruly speculative capitalism would thoroughly transform the city’s outlook. I was mostly impressed by the city’s extensive metro system, called “the tube,” enabling my classmates from art school and I to pop up in various parts of town in no time: a first fragmented real-life urban experience. Paris became the second visited metropolis shortly thereafter, in its classical elegance a clear counterpart to messy London. I bought neither pictures nor books on both cities. It took until meeting Keppel’s book on Paris (Entre Entree, 2014) many years later to learn with what different focus one could roam through cities, and with what different approach such free explorations could be translated into photobooks. The question remains as to whether the Paris from touristic picture books is even the same city as the one that ran through Keppel’s scanners and printers.

The tone was set with Reprinting the City (2012) on the small Dutch city of Den Helder, which is home to a large marine base. It is the first of the four books that Keppel laid out and edited in collaboration with the designer and publisher Hans Gremmen from the Amsterdam-based publishing house Fw:Books. The book’s size is A4, the default copying paper format, and the following three books keep to this. It can be read as a stack of documents against the grain (the mode is more medium-focused than documentary). In the cover image, a dotted halftone screen overrules an image of calm waves on the surface of the ocean. A black stripe emerges from an out-of-sync double printing of the same motif, overlaid at the edges. Discarded objects figure prominently, including DVD players, disk drives, and record players. The thrift store and the street are pleasure grounds for Keppel’s eyes. He is a “street comber” (straatjutter) according to the artist Roeland Zijlstra, who wrote a short afterword to this book. The comber normally is someone who combs the beaches for treasures that might have washed ashore. Zijlstra furthermore notices that Keppel’s way of rendering discarded objects means that “he removes from the remainders of life the sadness that adheres to them and he exposes an underlying character—tender robust radiant intimate.” These objects become accidental artworks.

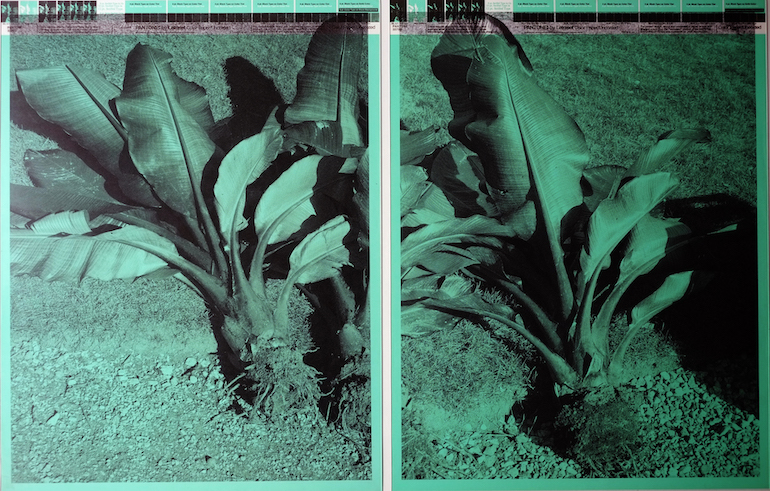

A key feature of Keppel’s practice is that it is recursive. Already in Reprinting the City there are a few indicators of a recursiveness that becomes much more pronounced in later works. There are photographs of prints lying on the floor, their edges curling up, and photographs showing images (misprints perhaps) that might appear elsewhere, too. There is a flat file cabinet placed on its side. There is a playing with halftone screens. In Entre Entree, Keppel took these experiments a step further. He stayed in Paris on two residencies for a full year, at the Van Doesburghuis in Meudon-Val-Fleury, a combined studio and living space designed by Theo van Doesburg in the 1920s, and at the Atelier Holsboer in the Cité des Arts at the center of town. Keppel circled around the city’s busy ring road, the Boulevard périphérique, and explored the city’s outskirts. Façades of postwar modernist or brutalist buildings, entrances, doors, marble, and the occasional exotic plant feature prominently. Paris offered a new passage into Keppel’s recursive world of strolling, picturing, scanning, printing, reprinting, and of photographing studio settings. For the first time, he and Gremmen included copper-like golden prints (the originals of which Keppel prints on Chromolux paper), heightening the sense of elegance that adheres to Paris, and emphasizing the dreamlike quality of Entre Entree.

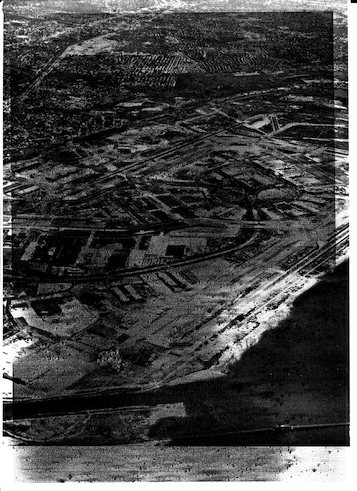

Keppel honored the city he spent the least time in (physically) with the heaviest tome. Whereas the first two books are relatively modest, Flat Finish (2017) is a heavy stack of crisp and clear A4-sized paper. “It is so New York,” said the photographer Ken Schles about Flat Finish. The city wears differently than Paris, is much more unruly in its architecture, despite the solid grid structure of its layout and the ever-polished “renewal” taking place in a Manhattan ruled by speculative flash capitalists. Keppel’s un-iconic vision of New York is as far removed from any tourist guide as possible. When the Empire State Building comes into view, it is a heavily pixelated dilution from tweeted pictures. The second-handedness of the city comes to the fore here. Keppel scanned the websites of sellers of reused building material before coming to New York. He examined the archives of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal before coming to New York. Upon arriving in the city, he already had a focus on the recycling of the city which eternally rebuilds itself. Of course, this once again looped back into Keppel’s own practice of circling and recycling. As the artist and writer Adam Bell (who teaches in New York City) remarked in a review published in the The Brooklyn Rail in March 2018, Keppel’s “repurposed images function as building blocks for [his] own metropolis while also pointing to the regenerative and iterative process of both the built world and Keppel’s image-making.”

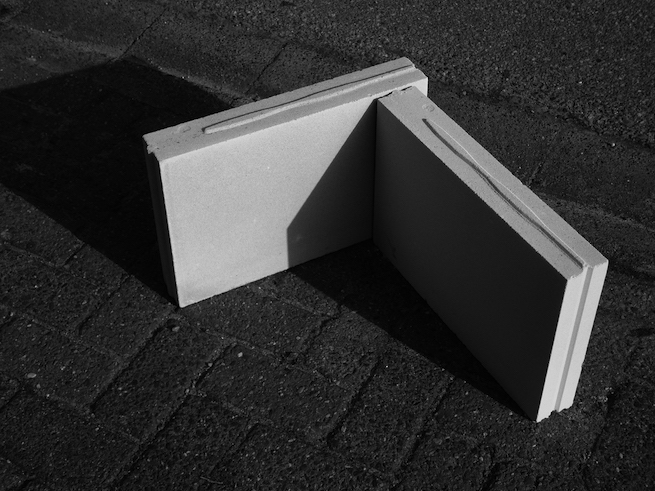

Keppel appropriates the cities that have become the locus of his books (the city mostly being a geographic limitation determining the working terrain for a certain period of time) and adapts them to the iterative processes of his printing obsessions. How would the city of Amsterdam, which he adopted as his home and where his studio is located in the postwar outskirts, be incorporated into his image world? The fourth “city symphony” is the most elaborate epitome of Keppel’s work to date. With every new book, the domain expanded with regard to image types and sources to be included. While in the earlier books only the exceptionally well-versed city expert would recognize where the images originate, in his new book Keppel included detailed notes about his sources in a type of coda. His eye for intriguing details is contagious. Details that nearly everybody rushing from A to B would not notice become monumental in Hard Copy Soft Copy (2021): hand-painted numbers from the Second World War still visible here and there, flattened house numbers from the days of the Amsterdam School building style (1920s and 1930s), tape marks on the sidewalk, or concrete cylinder leftovers from public construction works. In Hard Copy Soft Copy, Keppel weaves many more strands together, from his minute photographic observation of architectural details or of prints in flat file cabinets to various found “readymades” in the streets—or even found diapositive slides originally belonging to the Stedelijk Museum, showing artworks from their collection by artists such as Jackson Pollock, Piet Mondriaan, and Joel Shapiro. There is a page scanned from the 1971 novel Een avond in Amsterdam (An Evening in Amsterdam) by the poet and writer K. Schippers. This author is an astute observer, too, with a keen eye for unattended details and the serendipitous: “Sometimes the curb is just a sidewalk tile, situated vertically, or a brick, placed on its side. Never similar, always a difference of levels. Never connected perfectly, curbs. See, there’s a crack between these zig-zag shapes that were meant to connect them tightly.”

The exhibition Hard Copies at Camera Austria in Graz will be the first exhibition in which selections from all four of Keppel’s city projects will be brought together and respond to one another in space. The roomy room of Camera Austria will contain the cities of Den Helder, Paris, New York, and Amsterdam, and in the spirit of Keppel’s recursive practice, also a few freshly processed prints following the artist’s first real-life encounter with Graz while preparing for this very show in the age of restricted access to foreign cities.

Whereas the images in Keppel’s books could be considered “soft copies,” the exhibition is built up from “hard copies.” Where the original is, or even what an original is, never becomes clear. Some prints made for exhibitions are discarded afterward. The objets trouvés, which are now in spatial interaction with the prints (in the books they are incorporated within the flat image-making process and must conform to a single format), hesitate between becoming sculptures or remaining what they were when falling into Keppel’s hands: waste materials, discarded objects. The printed works leave their A4 comfort zones and appear in various sizes, framed or unframed. The material quality of the various paper types plays its part, from the colored Pantone sheets to the thin papers that run through Keppel’s old Océ 7055 toner copier. The Océ devices were still in use in the 1990s as large document copiers, for example by architects and engineers. By running the same images through this machine multiple times, architectural rhythms can be established in the exhibition space, while each print has its peculiar deviations and traces left there by the printing process. In the exhibition, the many different facets of Keppel’s working methods and fascinations—focused and divergent in equal measure—are brought together in a manner reflective of the searching and associative character of his work. The books on the tables, the found images, the found objects, and the prints on the wall are arguing about who is the master and who is the copy.

Stephan Keppel (born 1973 in Anna Paulowna, NL) studied autonomous art (1994–98) at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague (NL) and has since worked primarily with photographic and printmaking techniques. He has had his studio in Amsterdam (NL) since 2003. Last year he started a printmaking studio in his family’s former farmhouse in his hometown. The book projects Reprinting the City (Den Helder, 2012), Entre Entree (Paris, 2014), Flat Finish (New York, 2017), and Soft Copy Hard Copy (Amsterdam, 2021), all published by Fw:Books in Amsterdam, were acquired for various collections, for example the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam (NL), the International Center for Architecture in New York (US), and the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal (CA). Recently Keppel won the Somfy Photography Award 2020 with an installation at the Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam.

Taco Hidde Bakker (born 1978 in Heerde, NL) is a writer, teacher, translator, and curator in the field of the arts, specializing in photography. He studied at two art schools and obtained an MA in Photographic Studies at Leiden University (NL). He has contributed his writing to numerous artist’s books, catalogues, and magazines, including Camera Austria International (AT), Foam Magazine (NL), British Journal of Photography (GB), and TRIGGER (BE). Bakker is the author of the text collection The Photograph That Took the Place of a Mountain (Fw:Books, 2018). He teaches theory at Utrecht University of the Arts (HKU) in the Netherlands.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.