Press information

Laura Mulvey & Peter Wollen –

Intersections in Theory, Film, and Art

Infos

Press preview

10.6.2022, 11 am

Opening

10.6.2022, 6 pm

Artists’ talk with Laura Mulvey

11.6.2022, 1 pm

Duration

11.6. – 14.8.2022

Opening hours

Tue – Sun and bank holidays

10 am – 6 pm

With works by

Faysal Abdullah, Holly Antrum, Victor Burgin, Em Hedditch, Mary Kelly, Mark Lewis, Laura Mulvey, Kerry Tribe, Peter Wollen

Curated by

Oliver Fuke & Nicolas Helm-Grovas

Press downloads

Press Information

Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen are best known as film theorists and filmmakers. As writers, they made highly influential interventions in film theory such as Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and Wollen’s “The Two Avant-Gardes” (both 1975). Between 1974 and 1983, the duo made six films together. Across writing and filmmaking, Mulvey and Wollen’s works bring into contact semiotics, feminism, psychoanalysis, and histories and theories of the avant-garde. After the mid-1980s, they worked separately on numerous projects.

Griselda Pollock describes the 1970s context that shaped Mulvey and Wollen’s work as an “avant-garde moment”: an artistic and critical field characterized by overlaps and interactions between independent cinema, conceptual art, feminist appropriations of psychoanalysis, and the reanimation of activist practices and reinvigorated production of theoretical discourses relating to gender and sexuality. As Pollock describes, feminism was a defining point of orientation for this avant-garde. The exhibition Intersections in Theory, Film, and Art attempts to use Mulvey and Wollen’s work to evoke this conjunction and to raise questions related to the temporalities of “avant-gardes” and the archive, by juxtaposing films, documentaries, historical materials, and artworks. Given the context of Camera Austria, the exhibition places a particular focus on Mulvey and Wollen’s engagements with photography. In a contemporary moment characterized by the prominence of theoretical discourse in art, and in which art is frequently defined as a form of research, it is useful to return to Mulvey and Wollen. The exhibition provides an opportunity to examine their movements between theory and practice; to view some of the “theory films” and documentaries they made together and separately; and to see the traces of various research-based curatorial projects. What does a “belated” encounter with this transdisciplinary, transmedial practice—and its connections and dialogues with those around them—tell us about the present? And what does a retrospective view make visible in this work that was not apprehensible at an earlier moment?

Photography is a consistent—though little commented on—thread in Mulvey and Wollen’s writing. As early as 1968, in an essay written for New Left Review and republished the following year in his book Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, Wollen made the photograph central to his film theory. Seeking to account for the photograph’s particular relation to the world without privileging a realist film poetics as a result, Wollen drew on the American semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce, introducing Peirce’s term “index” to film theory, and characterizing film as an interplay between “indexical,” °“iconic,” and “symbolic” registers. This problematic continues in Wollen’s writing at the end of the 1970s, when he more directly took on the question of the relationship between art and photography’s “automatic production of information” (“Photography and Aesthetics,” 1978, p. 9), a line of investigation that turned his interest toward photo-conceptualist work by artists such as Victor Burgin, Alexis Hunter, John Stezaker, and Marie Yates.

“The Hole Truth,” one of Mulvey’s earliest texts, meanwhile, which was published in the feminist magazine Spare Rib in 1973, was about the photo series and collages of Penny Slinger. Drawing attention to Slinger’s feminist continuation of Surrealist methods, Mulvey interpreted this work as dislocating patriarchal ideology through its reorganization of stereotypical gendered imagery, following the threads of unconscious fantasy from a woman’s perspective. A similar argument reappeared in Mulvey’s engagement with a more detached version of such techniques in work by Victor Burgin and Barbara Kruger in the mid-1980s. In a review of their work published in Creative Camera in 1983, she pointed again to the importance of psychoanalysis for critiquing the social construction of “masculinity” and “femininity,” but also placed emphasis on the importance of “reverie and flashes of recognition” as a more open-ended and associative, less didactic, manner of continuing this politics of representation. Both here and in a text of the same period for a photography exhibition in Canada (“‘Magnificent Obsession’: Introduction to the Work of Five Photographers,” 1985), Mulvey takes up the cinematic as a perspective on the still image, and vice versa, thinking through mise-en-scène, visual fascination, and narrative across both media.

The photographic is also invoked in Mulvey’s most significant dialogue with an artist, Mary Kelly. As Wollen wrote in reference to Kelly’s work of the 1970s, her practice was characterized by “the rigorous non-use of photography”: a frequent use of the index or trace that made photography conceptually central while literally absent (“Photography and Aesthetics,” 1978, p. 27). The exchange between Kelly and Mulvey (and to a lesser degree Wollen) goes back to the early 1970s, when both were in the same feminist reading group. Kelly reviewed Mulvey and Wollen’s 1974 film Penthesilea: Queen of the Amazons in Spare Rib, and later remarked on how the film influenced her artwork Post-Partum Document (1973–79); Mulvey reviewed Post-Partum Document for Spare Rib in 1976, and Kelly herself appears, along with her work, in Mulvey and Wollen’s 1977 film Riddles of the Sphinx. Mulvey would maintain this conversation in the following years, writing about Kelly works such as Interim (1984–89) and The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi (2001). In this exhibition, Kelly’s Primapara (Bathing Series) (1974), a photographic series related to Post-Partum Document, marks this multidecade dialogue.

In the essay “Fire and Ice” (1984), Wollen engages with the work of Roland Barthes, discussing the relation of photography to time, film, narrative, and death. Seeking to problematize the assumption that photography captures a frozen instant in the past while film unfolds in a perpetual present, Wollen turns to Bernard Comrie’s detailed work on the grammatical category of “aspect.” Photographs typically raise a question: Should the signified of the image be conceived as a state (stable, unchanging), a process (changing and dynamic, seen from inside as ongoing), or an event (changing and dynamic, seen from outside as complete)? The combination of these three categories, Wollen argues, also suggests a minimal story form. Louis Lumière’s L’Arroseur arrosé (The Sprinkler Sprinkled, 1895), one of the first cinematic narratives, has such a structure: “a man is watering a garden (process), a child comes and stamps on the hose (event), the man is soaked and the garden empty (state).” This implies that “the semantic structure of still and moving images may be the same or, at least, similar.” These reflections on the semantics of time provide Wollen with a framework through which to discuss works by James Van Der Zee, Robert Capa, and Chris Marker.

In “Cosmetics and Abjection: Cindy Sherman 1977–87” (1991), Mulvey reflected on Cindy Sherman’s early Untitled Film Stills, pointing to how these portraits complicate the relationship between stillness and story: the tableau or “pregnant moment” implies a before and after that can never be known to the viewer, suggesting and denying narrative with the same gesture. This theme of the contradiction between stasis and narrative signalled by women’s appearance on camera is one that goes back in Mulvey’s writing at least to “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in 1975. And it returns in Death 24× a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image (2006), a book-length meditation on these questions. Gathering up the motifs of the uncanny, the fetish, the index (now thought through in relation to its apparent crisis in the digital era), the book unspools a series of readings of other writers (Freud, Barthes, Bellour) and cinematic objects (Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 Psycho and Douglas Gordon’s 1993 24 Hour Psycho, for instance), elaborating ideas of “the possessive spectator” and “delaying cinema.” Ultimately, the book becomes a reflection on temporality and history, including a reflection on Mulvey’s own past work.

In “Barthes, Burgin, Vertigo” (2001), Wollen extends his discussion of Barthes and photography. According to Wollen, Barthes’s work gave Burgin an alternative to the analytical philosophy of language that occupied other conceptual artists. In particular, the argument in Barthes’s essay “Rhetoric of the Image” (1964) prompted Burgin, throughout the 1970s, to try to find ways of combining text and image that would compel viewers to question the ideological function of photography. Wollen suggests that the topics and artistic strategies that Burgin explored and experimented with shifted in accordance with the transitions in his theoretical interests, moving from semiology to psychoanalysis, from Barthes to Freud. By the early 1980s, Alfred Hitchcock became “an increasingly important source for Burgin, as the master who ties the knot that binds together photography, scopophilia, fetishism, dream and psychoanalysis.” The latter also links Burgin to writing in Screen in the 1970s, notably Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure.” The inclusion in this exhibition of Burgin’s Gradiva (1982) signals—and hopefully extends—the literal and virtual conversations between Burgin, Wollen, and Mulvey.

This engagement with “the photographic” and related notions is legible in many of Mulvey and Wollen’s film and video works—those they worked on in collaboration and those produced separately. In particular, the photographic image’s relation to narrative, to other categories of images or signs, and to temporality, are recurring concerns. Penthesilea gathers an archive of evidence to reconstruct a mythic narrative (the Amazon myth), which is presented for an analysis carried out jointly by the filmmakers and spectators. A documentary about a fiction. Or a fiction made of documents. A similar dialectic is apparent in Riddles of the Sphinx. Its main narrative section is preceded by a sequence of images of the Egyptian sphinx where the camera seems to enter the grain of the celluloid filmstrip. Then, in the second half of the story, the 360-degree pans forming the sequence enter the genre of the landscape film, capturing a park and shopping center. Finally, the appearance of Mary Kelly and Post-Partum Document, in film and video watched by the characters, inscribes the movement between document and language from Kelly’s work into Riddles of the Sphinx, in a mise en abyme, one that is exemplary of the connections of Pollock’s 1970s feminist “avant-garde moment.” Both films provide a documentary record of the two filmmaker-theorists: Wollen in Penthesilea, Mulvey in Riddles of the Sphinx.

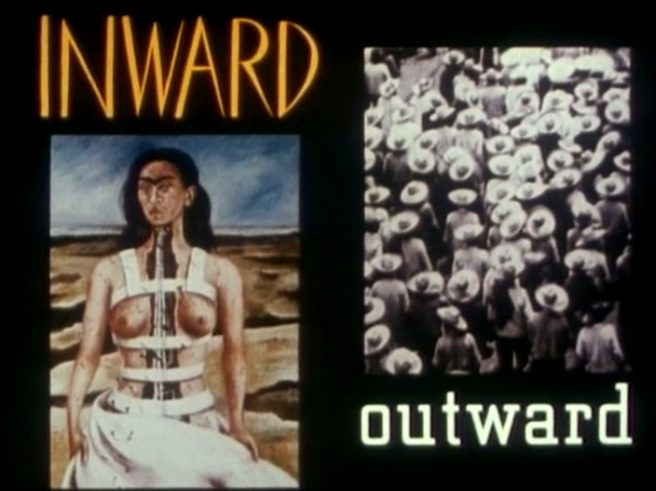

Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti (1983) examines two artistic practices, alternating and intertwining them to illustrate affinities and contrasts—painting and photography, personal and political. While Kahlo has become an artistic celebrity since the film was released (a process Wollen later described as “Fridamania”), now the film is perhaps more interesting in the way it accords equal importance to Modotti, a less well-known photographer. Wollen’s documentary Images of Atlantis: The Photography of Milton Rogovin (1992) focuses on the American photographer, who took pictures of working people, often more than once and at regular intervals, both in the workplace and at home. In one early series, Rogovin published a portfolio of photographs focusing on the congregations of Black storefront churches together with an accompanying text by W. E. B. Du Bois. A later series was on miners from different countries, including Germany, Scotland, and Zimbabwe. Wollen’s film includes people photographed by Rogovin, who speak about their experiences and how they felt about having their photograph(s) taken by the artist, thereby raising questions regarding the ethics of social documentary photography.

In 1994, Mulvey made Disgraced Monuments with the artist and filmmaker Mark Lewis. The film examines the history and fate of public monuments built in the former Soviet Union after 1918. Disgraced focuses on these statues, originally produced following a government resolution issued by Vladimir Lenin and Anatoly Lunacharsky, but it inevitably raises broader questions about public monuments and, to a certain extent, foreshadows debates that have become commonplace in North America and Europe. 23rd August 2008 (2013), a collaboration between Mulvey, Lewis, and Faysal Abdullah, is a film that consists of two shots: a brief opening shot of the Al-Mutanabbi Street book market in Baghdad and an unbroken twenty-one-minute monologue delivered by Abdullah. Here, as Mulvey has explained, he “gradually builds a portrait of his relationship with his younger brother, Kamel, and in the process evokes the lives of Iraqi intellectuals of the left.” The work is a double portrait: the first, photographic, of Faysal; the second, verbal, of Kamel, his life, character, intellectual project, and tragic death at the hands of unknown assassins.

Around and within these writings and films are other materials—notes, workbooks, drawings, diagrams, traces of collaborations and conversations with others—which are also in this exhibition. Constructing a constellation of films, artworks, documents, and library material allows one to observe how recurring concerns traverse different fields and media. It also indicates how their work forms an archive—one that leads into and overlaps with other archives—made up of films, texts, documents, ideas, and arguments. This archive is available for others to activate. In Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (2006), Em Hedditch works with Mulvey to reread her 1975 essay, embedding it in the archive of images and sounds composed by classical Hollywood cinema. In Here & Elsewhere (Kerry Tribe, 2002), Wollen (off-screen) reads a series of questions to his daughter Audrey, staging a dialogue on present and past, time and space, one place and another. In her engagement with Wollen’s archive of documents (now in the British Film Institute in London), Holly Antrum has created a fictional researcher who navigates the paper traces of another person’s intellectual inquiry. Presenting these materials together, the exhibition seeks to productively blur the lines between archive and artwork, theoretical and artistic discourse, and make these resources available to others.

Oliver Fuke & Nicolas Helm-Grovas

Oliver Fuke, born 1987 in London (GB), is an independent researcher. His projects include Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen: Beyond the Scorched Earth of Counter-Cinema and Yvonne Rainer: The Choreography of Film. Together with Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom, he is currently working on an exhibition of Trevor Mathison’s work. Fuke has also developed many exhibitions and projects with artists.

Nicolas Helm-Grovas, born 1988 in Vigo (ES), is a writer and academic. His writing has appeared in Oxford Art Journal (GB), Radical

Philosophy (GB), Moving Image Review & Art Journal (MIRAJ) (GB), and various books and catalogues. He teaches at Arts University Bournemouth (GB) and Oxford Brookes University, Oxford (GB).

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.