Stephanie Kiwitt

Dialogues

Infos

Opening

7.12.2016, 8 pm

in the frame of CMRK

Duration

8.12.2016 – 19.2.2017

Curated by Reinhard Braun

Free Shuttle to the opening

Vienna – Graz – Vienna

Departure Vienna: 7.12.2016, 3 pm, Haltestelle Oper, Bus 59 a

Departure Graz: 7.12.2016, 11.30 pm,

Burgring 2, 8010 Graz

cmrk.org

Opening hours

Tuesday – Sunday, 10 am – 5 pm

Intro

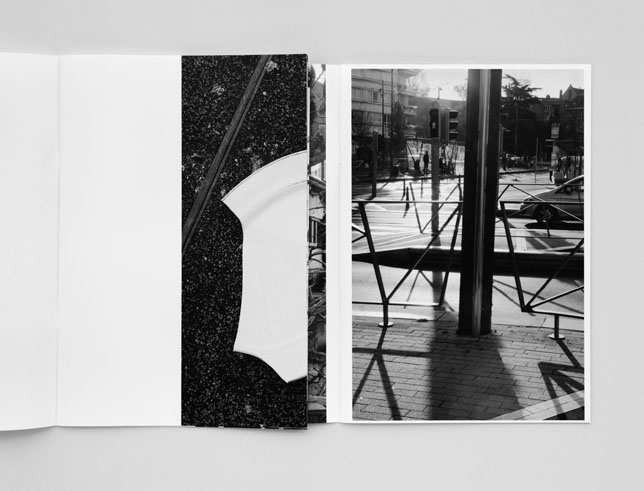

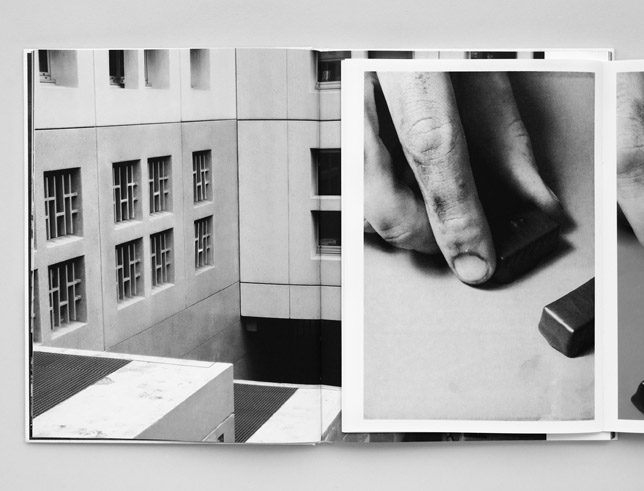

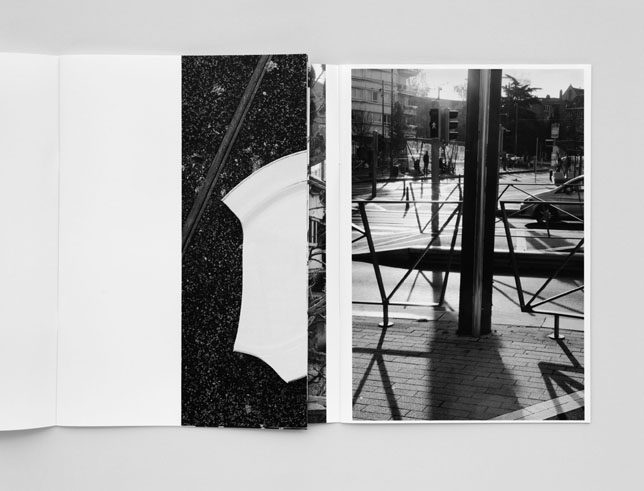

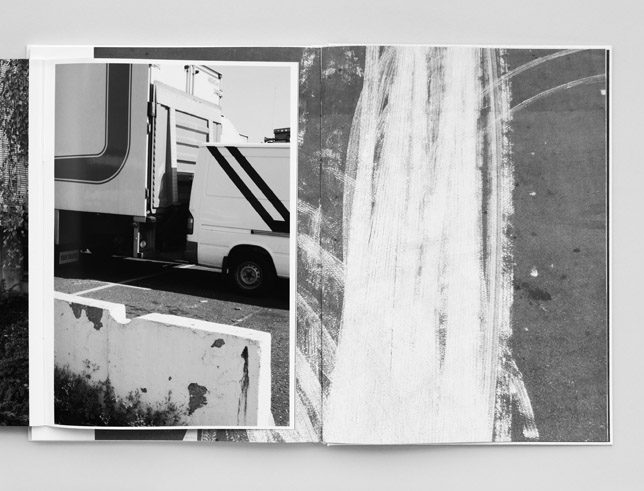

In »Dialogues«, the German artist Stephanie Kiwitt, who resides in Brussels, has for the first time compiled various works from recent years that take the form of publications and exhibition projects in a joint context. New junctures arise from image to image, never before seen in this way—each new image is a leap through time and space, from Belgium to Marseille, Prague to Ghent … Or perhaps these encounters are actually collisions rather than new junctures? Sections, cutouts, images extending beyond their edges, leading away, leading somewhere else—perhaps into a different picture? Kiwitt succeeds, in a unique way, at situating her photographs, series, and books along this threshold where a description opens and facilitates something rather than formulating and concluding it. This opening does not evolve without help, for it must be initiated—through images arising not randomly and also not incidentally, but which on the other hand don’t pretend that they have always known best, images with an inherent sense of restraint, through which the images foster a dialogue, both between the images themselves and with the beholder.

The exhibition is accompanied by a homonymous publication in the Edition Camera Austria, with texts by Reinhard Braun, Steven Humblet, Tina Schulz, Carsten Tabel, Eveline Vanfraussen, Bart Verschaffel, and numerous b/w illustrations by Stephanie Kiwitt.

Read more →Stephanie Kiwitt

Dialogues

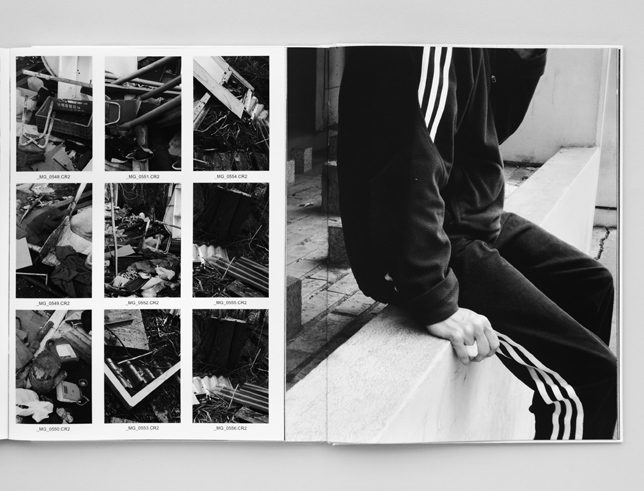

In the scope of the exhibition “Dialogues”, the German artist Stephanie Kiwitt, who resides in Brussels, has for the first time compiled various works from recent years that take the form of publications and exhibition projects in a joint spatial context. These works include “Máj/My”, presented for the first time in full this past summer at Les Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, “Choco Choco” (2015) and “GYM” (2013), both on show last year at WIELS in Brussels, and the publications Four Oranges, Some Office Buildings, Woman’s Legs (2015), Wondelgemse Meersen (2012), and Cornerville (2008). These photographic series and books are complemented by a reprint of the artist’s book Capital Decor, first published in 2011 in the form of a leporello or accordion fold.

Now, for the exhibition at Camera Austria, Kiwitt has gone far beyond simply selecting and newly constellating certain works from these series and books to instead arrange the books themselves and the prints from the series in her studio, superimposing them, rephotographing these constellations, and enlarging them as black-and-white laser copies in a copy shop. She then positioned the copies in two rows above the exhibition space. The original differences in format—discrepancies between colour and black and white, between print and book page, between materials and surfaces—are unified without exception in this new pictorial space. This is especially remarkable considering that Stephanie Kiwitt usually works in her series with the contrast between colour and black and white, sometimes even with the contrasting of different formats. So in pursuing this kind of presentation through a unified visual format, the artist has given something up, and for the most part one cannot even say that the original works are represented through this new form—something totally different has emerged, yet without the viewer being able to say precisely what at first glance.

Initially, the inner logic of a specific work, its layout and arrangement or the dramaturgy of a book, was disrupted or suspended: for example, the selection of specific image pairs and the confrontation between colour and black and white as found in “Choco Choco”; the chronological order of selected contact prints as found in “Wondelgemse Meersen”; or the shift between colour and black and white, human and machine, as found in “GYM”. Each of these systems of order formed a foundation for the selection of images, their combination, their sequence, the series’ narratives—a process involving a great deal of time, for Kiwitt repositioned her photographs on the walls of her studio again and again, taking this or that one down, hanging others up, exploring and culling, until a series or a book emerges.

Obviously, these established orders have been shattered in the exhibition “Dialogues”, with the structuring and selecting of combinations of books and prints from various series resulting in a different (new?) established order. In the “Dialogues” exhibition, “Choco Choco” encounters Wondelgemse Meersen, “Choco Choco” encounters “GYM”, Cornerville encounters “Choco Choco”, Wondelgemse Meersen encounters “Máj/My”, and so forth. New junctures arise from image to image, never before seen in this way—each new image is a leap through time and space, from Belgium to Marseille, Prague to Ghent … Or perhaps these encounters are actually collisions rather than new junctures?

For many years now, Kiwitt’s series—and the artist works solely with series—have very fundamentally posed the question as to whether photographic images are capable of establishing a meaningful system of order that might speak about the centrifugal, seemingly disintegrating classifications of our reality, that could trace and manifest these realities or make them accessible. The photographic series constantly engage with realities and foster a tension between that which the artist encounters and the images themselves. In “GYM” or “Choco Choco”, the constructed nature of the images is more apparent than in Cornerville or “Máj/My” despite the lack of stagings per se. Yet one can never be entirely sure of which relationship the construction of images and their contingency, or perhaps their letting-it-happen, actually have—for they often give rise to the impression of being both randomly created and purposefully designed.

The sense of visibility rediscovered in her projects and books, in the images and from one picture to another, thus seems to move along a threshold subject to the negotiation of planning and coincidence, beauty and being-repelled, interest and renunciation, fascination and revulsion in the image. For don’t bodies that are being conditioned (“GYM”) in their concentration on becoming better, becoming healthier, becoming more beautiful, being loved also reveal a pathological stroke of social consciousness that repels us? Don’t the seductive streams of chocolate and the beauty of precision of their final form (“Choco Choco”) expose a fetishism of indulgence, and thus also a dependence on substances that utterly unnerves us? Doesn’t the beauty of an urban no man’s land (Cornerville, “Wondelgemse Meersen”) also convey a manner of empty social space, its downfall and its dissolution, frightening us again and again?

The radicality of Stephanie Kiwitt’s work, if this phrasing fits, is expressed first and foremost subtly—through the consistent manner in which she implements the respective concept of the series and books, in the precise construction of the images, in the coherency of combinations which nonetheless never push their way into the foreground, never lay claim to exclusivity but rather retain the openness of a draft. The tension between the established order of the images and that which adheres to reality ever remains in place. Inherent to the images, then, may also be a type of uneasiness, because they simply will exactly mirror the subject matter being rendered, because inscribed in the photographs is still the logic of the gaze, of the selection, of the concatenation of the images. This moment of tension is ultimately found in the relationship between two images—at that juncture where the other image collides, a transition, a leap, a gap that facilitates, devises, constructs, follows a principle that is equally devised and constructed, but which does not reconcile one image with another. Instead, it allows the images to mutually query one another, and most definitely offer reciprocal commentary. The progression of the photographs remains fragile, represents a venture, and never aims for completion. The artist seeks, in the individual image, not the expressive or the purportedly important, special, meaningful. She distrusts the individual image and its indiscriminateness, as evidence and authentification, so that an image always presupposes or generates another. Be that as it may, it still impels the narrative and remains a point of departure for the transitions from this image to another.

So what does this dissolution and regrouping, so evident in “Dialogues”, actually mean—disrupting already established orders, replacing orders with other ones, fully re-examining one’s own work or exploring it in terms of cohesive or overarching logics of image classification? Can the “original” topics, contexts, and narratives even still be discerned, or are they perhaps even intensified? Does it involve the resistive quality of the works themselves, the experience that the images only reluctantly transition to the next new image (an image from a completely different series that owes its existence to utterly different explorative questions)? Does the process of rearranging once again lead back into the images themselves, image for image, reminding them to start analyzing again and to think about them in a different way? So what does it now mean to dismantle or to repeat the classification of images in a self-contained series on another level? What does this repetition mean? Are the fissures between the images heightened, the collisions forced, maybe even dramatized? In this exhibition, does the artist place even more emphasis on the distance between the images, or rather on their similarities, their commonalities, which cannot only be conceived in terms of form, but are also situated on the level of their charged relationship with things in reality, in this specific relation to reality in which Kiwitt immerses her photographic production?

According to Jacques Rancière, politics is precisely that activity that disrupts a given sensible order, and art is not political because of its themes or its statements, but instead by deviating from certain ways of being together or apart and certain forms of experience. And that which deviates from certain forms of togetherness is not primarily the new, the extraordinary, the special or surprising, the never-before-seen, demanding attention, but rather the unexpected, the incidental and neglected, the always-already-seen and -given. Kiwitt’s image production seems to be driven by a desire to make the commonplace seem unfamiliar, to unmask its apparent naturalness as actually being a construction, to allow the improbable facets of its functioning to emerge all of a sudden, so as to show what it conceals, what it is basically reluctant to show. And this is not possible with just a single photograph, for images always need other images.

An image is never alone, writes Gilles Deleuze, for what counts is the relationship between the images. So what happens at the passage from one image to another? How does the construction of one image relate to the construction of another? What is taken up, continued on, refuted, viewed differently yet again? What emerges quite a bit later? In her books and in the exhibitions, Kiwitt repeatedly works with tableaux that compile images, or with double-page spreads and diptychs, with individual images inserted into tableaux, with groupings, with predetermined sequences, with a special dramaturgy of appearing and concealing, of showing and referencing. What arises in the process does not replace perception or a reality conceived in any which way; what arises is the establishment of an order via imagery that is neither comprehensive nor assertive of truth, yet it may be understood as a probing of realities, as a space, a visual space, placed at one’s disposal, considered reality, asserted, proclaimed, or taken as self-evident.

Stephanie Kiwitt’s books and photographic series indicate that, instead of presenting the world through imagery, we negotiate the world, exchange experiences, allow knowledge and meaning, criticism and alternatives, to circulate through imagery. It is a way of visually talking about the world. This may seem banal, but it forces us to relentlessly question the established order of the images, to distrust all visual narratives, for meaning is so strongly dependent on selection and arrangement. We are challenged to search for something in the images that they may not even show, perhaps cannot even show, at least not in terms of content, but rather in the way they interact with the other images. Maybe something is always missing from the images, maybe there is something like a blind spot, an area that cannot be reached and controlled, and we are called upon to search for something in the images that is not actually of visual nature. Not only does Stephanie Kiwitt seem to permit such gaps in her photographs; she indeed also fosters it—a sense of fragility of imagery.

However much the practice of Stephanie Kiwitt falls back on a structuring of images, however much her series remain incomplete, fragmentary, open to junctures, to additions, perhaps not by other images but the addition of a thought. Sections, cutouts, images extending beyond their edges, leading away, leading somewhere else, perhaps into a different picture, pointing out similarities where none were initially to be seen, while simultaneously avoiding any parallels or identities or even identification that would label the images as something special or arbitrary, make connections, permit transitions and passages from one image to the other, while insisting on the differentiation between the images—or, to paraphrase Georges Didi-Huberman, making differences visible by associating things. Kiwitt succeeds, in a unique way, at situating her photographs, series, and books along this threshold where a description opens and facilitates something rather than formulating and concluding it.

In this respect, “Dialogues” does not appear to contradict Stephanie Kiwitt’s practice to date. The artist has merely expanded her practice, with the incompleteness, the quest for new junctures and new concatenations, now threaded through the work of several years. She dissolves the logic of individual works, thus simultaneously indicating how they derive from a specific logic and opening up a space for us to explore this logic. The original systems of order are suspended in favour of a new reconstruction of imagery, in which case a work and a mindset can be sparked by the images, extending beyond the act of seeing, of viewing. In a certain sense, she reinforces the impression of the images being constructed, yet shows, at the same time, that this constructedness permits a querying of realities. This querying does not evolve without help, for it must be initiated—through images arising not randomly and also not incidentally, but which on the other hand don’t pretend that they have always known best, images with an inherent sense of restraint, through which the images foster a dialogue, both between the images themselves and with the beholder.

Reinhard Braun