Tetsugo Hyakutake

Postwar Conditions

Infos

Opening

7.12.2018, 8 pm

Artist’s talk & film screening

Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, 1953)

18.1.2019, 6 pm

Duration

8.12.2018 – 17.2.2019

Opening hours

Tue – Sun, 10 am to 5 pm

Closed 24.12., 25.12.

1.1.2019 open from 1pm–5pm

Guided tours

German, English

Free, on request:

exhibitions@camera-austria.at

+43 316 81555016

Curated by

Walter Seidl

Free shuttle to the opening

Vienna – Graz – Vienna

Departure Vienna: 3 pm, Bus stop Opera, Bus 59 a

Departure Graz: 11:30 pm, KM– Künstlerhaus, Burgring 2

cmrk.org

Intro

The exhibition by the Japanese artist Tetsugo Hyakutake, born 1975, leads back into history in a twofold way. On the one hand, he analyzes Japan’s history since World War II and how it has affected current identity formations within the country, which, for many decades, has been under the influence of the West, most especially the United States. The artist seeks to pursue a past that relates to issues of colonization, war, and other decisive historical events—themes that reflect on current issues of identity in Japanese culture and on the relationship between past and present, as well as the fractures between individual and collective memory. The artist juxtaposes archival material with his own photographs and negotiates various levels of temporality within the photographic dispositive. He often applies a special technique by treating photographs with chlorine to make them appear like historical documents and thus provokes an ontological leap between different realities—always raising the question of how Japanese identity and thought have come into being.

On the other hand, the project leads into the history of Camera Austria: already in 1975—at the time still in the Galerie Schillerhof in Graz, curated by Manfred Willmann—a solo exhibition presented works by Masaaki Nakagawa, and in the same year works by Seiichi Furuya. It was due to Furuya’s mediation and knowledge that other important exhibitions of Japanese photography were realized in Graz, for instance by Toshimi Kamiya (1978), Daidoh Moriyama (1980), Hitoshi Fugo (1982), Shomei Tomatsu (1984), and Nobuyoshi Araki (1992). Ultimately, a new exhibition space was inaugurated in the Eisernes Haus with an exhibition of Japanese photography. It is when considering these moments of very specific intercultural exchange about such contrasting visual cultures that I would like to mention the upcoming exhibition curated by Walter Seidl and also transition now to discussion on a political level.

Read more →Tetsugo Hyakutake

Postwar Conditions

Tetsugo Hyakutake analyzes moments of Japan’s history since World War II and how they have affected current identity formations within the country, which, for many decades has been under the influence of the United States and, for some, still is. The artist seeks to pursue a past that relates to issues of colonization, war, and other decisive historical events that reflect on current issues of subjectivity in Japanese culture and the relationship between past and present, individual and collective memory and history. Hyakutake juxtaposes archival material with his own photographs and negotiates various levels of temporality within the photographic dispositive. He often applies a special technique by treating photographs with chlorine to make them appear like historical documents and thus creates an ontological leap between different realities, raising the question of how Japanese identity and thought have come into being. With the economic boom culminating in the 1980s, which was supposed to make up for losing the war, and which stagnated in the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s, Hyakutake’s works raise the question of how the international positioning of Japan has been subject to critical scrutiny and how the personal is put to the fore via an introspection of the dialectics between self-determination and the perception through the eyes of the Other, that is, a Westernized gaze.

Regarding the parallelization of Japan being an island and nation at the same time—with specific ethnic conditions—raises the question of the essence of Japanese thought. According to Naoki Sakai, “the being of Japanese thought is assumed but never disclosed, and its esoteric essence is projected into the past, while this institution of knowledge is sustained by the insatiable desire for it.”¹ Sakai thus relates to Lacan’s psychoanalytical approach, which makes it impossible to satisfy desire as it continues to reproduce itself constantly. The existence and uniqueness of Japanese identity and thought, however, is due to about 270 years of the population’s seclusion on an island, during which contact to the outside world was cut off. This isolation ended in 1868 with the return of the Emperor and the decline of the Edo period. The reason for this was the US-led Perry Expedition in 1853, which aimed to establish trade agreements with Japanese ports, open the country’s economy, and widen its diplomatic relations. Thereafter, an empire following Western economic and cultural models was created as a hyperreality construct, which made Japan the second largest world power.

Belonging to the generation that has come of age in the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s, Hyakutake found himself trying to understand what it means to be Japanese today and how the Japanese subject is reflected upon within and outside of the country. According to Gilles Deleuze’s reading of David Hume, the “subject is defined by the movement through which it is developed. This movement of self-development and of becoming other is double: the subject transcends itself, but it is also reflected upon.”² Hyakutake is concerned with the cross-reflections that situate the Japanese subject somewhere between a self-contained entity and a US-determined cultural and economic being. Moreover, his work focuses on industry and the infrastructure of contemporary society, through which the artist seeks to decipher recent Japanese history and culture. A conflicted relationship with historically relevant sites comes across in his images of a multilayered visuality, which testify to an uncertainty as to their structures of representation. Hence, Hyakutake’s photographic output has an ephemeral, fleeting quality that poses questions about its subjects of representation. In between document and fiction, his images depict monuments that are part of Japanese history yet suffused with rays of light which blend history with the individual’s mortal coil.

Hyakutake’s reflections on contemporary Japan start with the developments following World War II. The artist is particularly drawn to the controversial debate concerning the responsibility of Emperor Hirohito, now called Emperor Shōwa, for the wartime atrocities committed by Japanese forces. The media hardly covered the topic of his leadership and responsibility during the war, which was generally considered taboo despite the fact that he had full power over the Japanese military according to the imperial constitution of Japan. He was the one who finally decided to end the war. Hyaku-take also focuses on General Douglas MacArthur, who oversaw the US occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1951 and the ensuing political, economic, and social changes. A three-channel video animation shows Japan’s surrendering Emperor Hirohito and General Mac-Arthur, as well as an image of the artist’s granduncle, who died in the Philippines, which Japan had invaded under MacArthur’s rule. The image was taken from a family photo depicting him shortly before he left for the war. Thus, Hyakutake’s photographic documents try to reconstruct history, yet always refer to the relationship between fact and fiction and the use of archival material, which can reveal as much about the present as about the past. The animated Japanese eye and body movements are in fact the artist’s own, referencing a distance between the self, the eye of the beholder, and the historicity purported in the respective imagery.

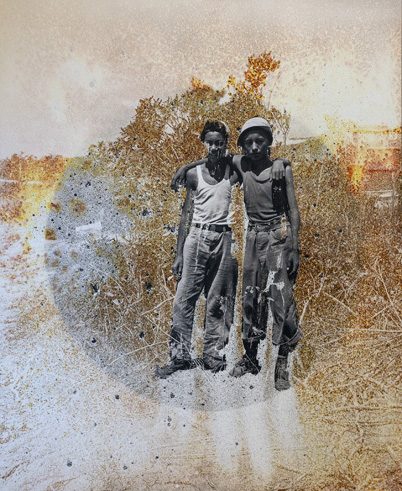

One of the main areas of US interference has been the island of Okinawa. Ever since the battle of Okinawa in 1945, US military bases have been stationed on this island and will continue to be, giving the United States a stronghold in the Pacific, from which to operate in case of the unforeseen. Okinawa represents only 0.6 percent of Japan, but about 75 percent of the US bases are located on the island, which is considered a contested site with many disputes between the Japanese population and US soldiers on issues of crime and inequality. With regard to the battle as one of the most severe in the Pacific during World War II, Hyakutake ponders the feelings of those who witnessed the atrocities, killings, and suicides. One manipulated photo depicts two boys in Iejima, whose original photo negative was supposedly taken by American soldiers after 1945 and which was acquired by the artist at an auction; likewise the photo of women in Okinawa at that time, who are surrounded by American soldiers.

Moreover, Hyakutake explores Japanese sites where preparations for war were already underway before World War II. He researched and visited such sites and then manipulated his own photographs accordingly. These sites include a torpedo test fire facility in a small port town in Nagasaki, a navy ammunitions arsenal as part of the Maizuru shipyard in Kyoto Prefecture, the Shime coal mine near Fukuoka, and poison gas storages erected in line with the Imperial Japanese Army’s Institute of Science and Technology’s secret program to develop chemical weapons, which was already launched in 1929. His technique involves bleaching photographs, which makes them look faded, cracked, and fragmented. These damaged photographs are representations of Hyakutake’s concern that the memory of the individuals suffering from misfortune might fade and fall into oblivion. The blurry surface quality creates an illusionary effect that asks questions about the authenticity of the image. At the same time, the artist frees the image from its factual qualities and turns the gaze to a different, volatile reality. In her recent publication, Michelle Henning talks about the “unfettered image,” as photographs seem to become more and more detached from a specific place in time. “Theorising photography in terms of its mobility demands that we pay attention to practices where the urge to ‘fix’ reality is either barely evident or explicitly struggled over, images that seem to play with perception, that offer themselves to us and then deliberately withdraw from our gaze.”³

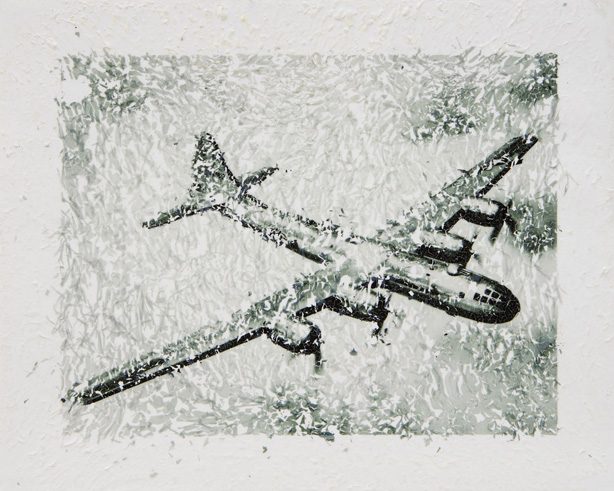

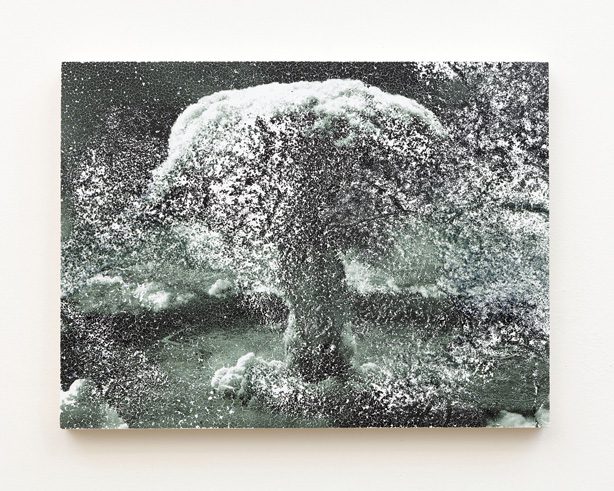

Hyakutake takes historically contested sites as point of departure and plays with the memory of such sites as well as the resulting moments of illusion or disillusion. The fact that the people in Okinawa experienced historical evidence differently than the readers of Japanese history books, has to be taken for granted. Yet, both relate to the essence of Japanese thought, as they create a “historiography that historicizes the conditions of possibility for the history of Japanese thought.”⁴ Concerning the processuality of historical events, one way to relate to their visuality is by confronting archive photographs, especially when it comes to such contested sites as Hiroshima. Here, the artist refers to the Trinity testing site in New Mexico, the actual bombing site as well as the aftermath and Hirohito’s visit, moreover to the B-29 Superfortress bombers operating against Japan’s major cities. Hyakutake employs a further trope when dealing with pictorial evidence as depicted in the war bonds he inherited from his grandfather. Here, Hyakutake prints or superimposes archive photographs as well as his own photographs over the original documents and thus mingles several moments of (visual) history that cannot be translated clearly from a present stance.

Early moments of industrialization can be traced in photographs of bridges, such as the Yalu River Bridge, a half-destroyed railroad bridge over the Yalu River between the Chinese city of Dandong and the North Korean city of Sinuiju built by Imperial Japan in 1911. A contemporary approach would be the expressway bridge in Nihonbashi in the center of Tokyo, which translates into as “Japan Bridge.” Formerly a wooden bridge, Nihonbashi was reconstructed with stone in 1911. The expressway was built along with during the same period as the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and facilitated the city’s huge growth in post-industrial times. By combining these images, the artist poses questions as to how Japan’s force has been recognized outside of its geographical territory and especially within a Westernized hemisphere, which is likewise self-critical and “never content with what it is recognized as by others.”⁵ In this respect, Hyakutake tackles the project of modernization, which, for Sakai, can be equated with the process of Americanization in the case of Japan. The latter has affected the country ever since the Perry Expedition and continued to do so through various dispositives of power. Yet, it “has been repeatedly deplored or extolled that Japan alone of the non-Western cultures was able to adopt rapidly what it needed from Western nations in order to transform itself into a modern industrial society.”6 Hyakutake explores the external influences of war that were part of this “modernization theory” and examines historical narratives and their antagonistic moments. His works try to contribute to a history that has been disrupted by the same power it has nested upon, culling images from archives whose relevance has been fading in the wake of the country’s excelling in economic grandeur and at the same time overcoming failure as a non-existent phenomenon in everyday Japanese culture and thought.

Walter Seidl

¹ Naoki Sakai, Translation and Subjectivity: On “Japan” and Cultural Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), p. 42.

² Gilles Deleuze, Empiricism and Subjectivity: An Essay on Hume’s Theory of Human Nature, trans. Constantin V. Boundas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), p. 85. Originally published in 1953.

³ Michelle Henning, Photography: The Unfettered Image (London: Routledge, 2018), p. 21.

⁴ Sakai, Translation and Subjectivity, p. 42.

⁵ Ibid., p. 154.

6 Ibid., p. 156.

Tetsugo Hyakutake was born in Japan in 1975. A graduate from of the University of the Arts in Philadelphia (US), he obtained a Master of Fine Arts master’s degree of fine arts from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in 2009. Hyakutake has exhibited in Tokyo (JP), Philadelphia, New York (US), Madrid (ES), Singapore (SG), and Taipei (TW). His work has been acquired by various corporate and public collections, including BlackRock (Philadelphia), Fidelity Investments (Boston, US), the Library of Congress (Washington, D. C., US), and the Carnegie Museum of Art (Pittsburgh, US). After participating as residence artist at the ISCP in New York from 2016 to 2017, Hyakutake is currently based in Japan.