Press information

Friedl Kubelka:

Atelier d’Expression (Dakar)

Infos

Press preview

10.6.2016, 10 am

Opening

10.6.2016, 8 pm

in the frame of CMRK

Buy Art from the Atelier d’Expression!

A(u)ktion initiated by Friedl Kubelka and Georg Gröller

performed by

Salvatore Viviano

music by

Ibou Ba

10.6.2016, 9 pm

INFOS

Artist talk

Friedl Kubelka, Alassane Seck (Atelier d’Expression, Dakar),a.o.

11.6.2016, 11 am

Curated by Maren Lübbke-Tidow

Free shuttle to the opening Vienna – Graz

Departure Vienna: 10.6.2016,

3 pm, bus stop Opera, bus 59 a

Departure Graz: 10.6.2016,

11:30 pm, < rotor >, Volksgarten

cmrk.org

Duration

11.6. – 14.6.2016

Opening hours

Tue–Sun 10 am – 5 pm

Press downloads

Press Information

Playful Countermovements

Imagine the following situation: a curator invites an artist to participate in an exhibition and then comes to realise that the artist has spanned a web of subversive practices that thwart both the conventional mechanisms of art production and those at play in an exhibition context. How might one connect such contrary movements? In view of this thwarting of mechanisms related to art production, it makes sense to shift the gaze to the work of the artist and her way of working. Yet when it comes to the thwarting of the mechanisms involved in the production of exhibitions, it is crucial to foster openness. It is beneficial to actually not know how each project will end so as to find new paths in the process.

The Exhibition—“Friedl Kubelka: Atelier d’Expression (Dakar)” introduces the artist’s most recent work. Reflection on her own role as an artist, which is related to the decision to increasingly withdraw her previous artistic work from the systems governing the art market, coincides with Kubelka’s interest in people who are engaging in artistic activity while remaining outside the dominant establishment. The exhibition by Friedl Kubelka is devoted to these so-called “outsiders” and their art. She visited the Atelier d’Expression in Dakar, a psychiatric clinic in Senegal, which gives patients an opportunity to pursue, among other things, artistic activity. The exhibition shows portraits of the patients. These works are supplemented by the artwork of those portrayed in Senegal. The latter assumes an essential position within the exhibition and will be sold at an a(u)ction organised by the artist to the benefit of the artist-patients. Becoming visible here, too, are Kubelka’s own (travel) experiences and the different levels of encounter with the city of Dakar and related structures.

The work and the exhibition require different points of access.

Working On and Against the Image: Behind Each Image Awaits Another—On the one hand, Friedl Kubelka presents her own work, which is clearly associated with her previous work as we know it. It deals with an act of contact initiation where two individuals enter into a relationship with each other, separated by the apparatus capturing the situation yet united through gazing into and through the camera.

Although a large portion of Friedl Kubelka’s œuvre involves portrait work, her artistic method is simultaneously always a way of working against the portrait. In fact, Kubelka constantly works against the idea of there being one valid picture. Her hourly, daily, or yearly portraits, all the way to a thousand-part portrait (“Tausend Gedanken”, 1980), are firstly time-cuts in the space of encounter between the artist and the person across from her; they speak of interplay among proximity and distance, of moving towards and away, or even deprivation. Perhaps they even speak more of the performance of encounter than actually presenting an image. The manipulative potential permeating her portrait sessions is especially evident in her films. The artist meets her protagonists with humour, devotion, or sometimes even with dispassion. The resulting images function as surveys of the status of both the person rendered and the image itself, a status which is constantly in motion. Stirring and touching unspoken norms without violently breaching them—this is the incredible strength yet also vulnerability of this œuvre, which cannot be termed documentary but rather brings forward the image as an event.

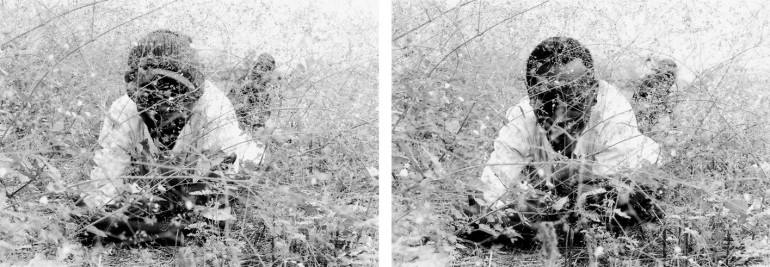

In the current portrait works, showing patients from the psychiatric ward of Fann Hospital in Dakar, it was important to the artist to maintain the integrity of her counterpart, and also to preclude the moments of derailment that repeatedly arise in her work—while especially (or once again!) making sure to fall short of expectations towards the represented vis-à-vis. Here we see no “outsiders”. This easily assigned ascription does not apply. Her protagonists are serious and tangible/unassailable. Their expressions or poses give no indication of an identity disorder. At times, art utensils like a paintbrush give an indication of their self-conception as artistically engaged individuals. Otherwise we—like the artist Papis (Babacar Gaye), whose face is largely covered by the grass in which he is resting—are left alone in the thicket of our diffuse conceptions of the people whom Friedl Kubelka came across in Senegal.

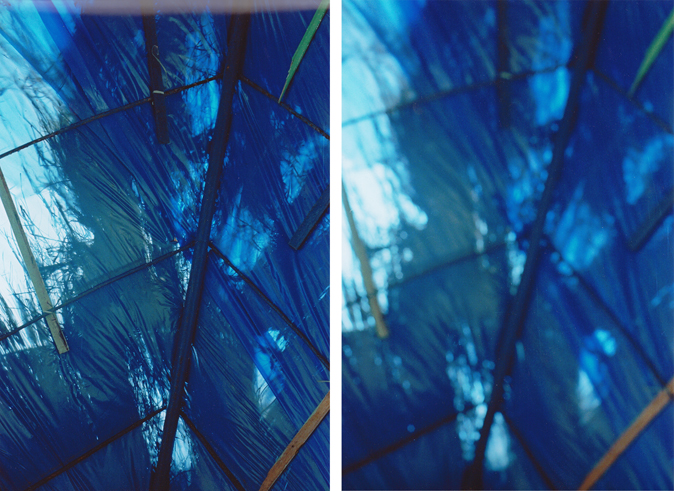

On the other hand, the exhibition speaks of different experiential levels owing to travel to a country that provokes a wealth of projections and ascriptions. The artist, as a purposely non-sovereign master of the traversed West African region, works with the inner and outer contradictions leading her through the country, and she lends visual form to these contrasts in photographs of architecture and urban structures, of their own seductive beauties and very real precipices. An artwork thus arose that may beg to be politically read, but in which, during the act of viewing, the personal realm of experience very clearly pushes itself in between and to the forefront again and again. This induces moments of disruption. Even just hearing the word “Africa” alarms us. We demand clarity, and objectivity, and knowledge, information, discretion, and precepts. All this must be conveyed by the work of a European artist who is moving within this space. All this may be of interest or known to the artist, but for her work on the image this expectation plays no role whatsoever. Kubelka expressly does not push aside the common, extant projections in order to arrive at an adjusted image that, in the best case scenario, conveys objectifiable knowledge or establishes an unassailable work. Instead, she presents herself through her images as a traveller and foreigner who is guilty/innocent, knowledgeable/lacking in knowledge, open-curious/full of angst and shame. Only one thing is pivotal: anything goes.

Breaking through Established Cycles of Use: Unsaleable/Saleable—These works originated through the impulses of a continually productive artist—without the definite intent to release the works, for instance in an exhibition format. One could say that Kubelka’s working approach is personal. In fact, it does repeatedly become clear how strongly the plane of very deep personal experience becomes inscribed into her artwork during the creative process, seeking qualification precisely here. As a form of constant self-questioning. At the same time, this idea of working “in and of itself” is already eminently political: as form of insistence on the autonomy as an artistically inclined subject, beyond cycles of use in which the work is engaged, when it becomes public.

In the case of the exhibition jointly developed here, the artist used the invitation to provocatively thwart the mechanisms of exhibition production. She did so by channelling “foreign” works into the exhibition—works by people who work artistically but would themselves never be able to find a place for presenting their artwork in our context. So while the artist, on the one hand, herself decided on the unsaleability of her work, she used her invitation to participate in an institutional context, on the other, to gain access to a space for those who can hardly garner visibility for their artistic work. But the subversiveness of her activity does not end here. It goes beyond Friedl Kubelka’s idea to integrate “foreign” works in the exhibition to actually have them be sold in an a(u)ction initiated by her, thus offensively marking them as “saleable”. With the aim of also ascribing value to these works—value that, of course, is also reflected by a price. With the aim of providing the artist-patients with a wage for their work. And with the aim of becoming more concrete and showing appreciation towards the Atelier d’Expression in the Senegalese city of Dakar and the artists working there in a way that is more than just ideational.

inside/outside: Speaking about the Art of Outsiders¹—If we consider the artwork by Senegalese artists introduced in the exhibition as the work of patients visiting a psychiatric institution, then we can localise them in the context of discourse on so-called “Outsider Art”. But does this achieve anything?

Today Outsider Art is used as an established concept of style, as if it actually denoted a specific style analogous to other genres. But those who take a more in-depth look will note that the works by the various artists subsumed here are hardly related. So what might Outsider Art really be? Indeed, it is not a style, it does not encompass a specific geographic area, it fails to delineate any clear time period, nor does it denote a particular artistic orientation.

So the question is whether a categorisation as Outsider Art is even able to imbue the creators of the artwork with a sense of (new) dignity. Or whether it would conversely serve to once again marginalise or even patronise them? Clearly, the acknowledgement of so-called “Outsider Art” represents a gesture of liberation, which has helped to discover unique works of art. In the case of the works channelled into this specific exhibition context by Friedl Kubelka, it is worthwhile to acknowledge that art can be created in unexpected places, and that its meaning does not necessarily depend on whether the originators are knowledgeable about art and its history—whichever history of art. What counts is the work itself, its aesthetic richness and complexity, the thoughts and references that it formulates, its precision and the risks it takes. The question of “inside” or “outside” is unimportant and debilitating, for it hampers understanding. For example, works of Art Brut have been traditionally treated as examples of “primal” art, existing beyond the confines of time and history. They actually all tell—often more than we would like—°“of a world that we believe to know. Behind superficial unworldliness, they spread out repressed realities, unfold inhibited yearnings, call for promises to be redeemed, and remind of ignored injustices” (Daniel Baumann). The exhibited works speak to all of the above. With the exhibition of Friedl Kubelka, we are leaving the corral in which outsider art has been enclosed and opening ourselves up to their work as art—and solely as art. This is how the artist Friedl Kubelka introduces it to us. And just as Friedl Kubelka has given the artist-patients names and is showing them as creative personalities in her photographs, now we can try to encounter them and their works in an open and unbiased way. Still, it remains to be seen as to whether we will succeed in this without stylising them as foreign matter or allowing them to degenerate into a symptom—not only in this project, but everywhere that we come into contact with so-called “Outsider Art”.

… and even Africa!—We won’t be able to avoid sticking our European eyes onto these images and adjust to the works with the trained gaze of our European, art-historical education—though with the knowledge that these artworks were created in a context in which we are not sure on which aesthetic concepts they are founded. We can try to place them in the context of their origination, that is, to criss-cross it with our knowledge about colonial history, interveined with racism, about the relations between Europe and the West African region. In 2001, Okwui Enwezor substantiated the reception of African modernity with “The Short Century”. A comparison of the photographs in our exhibition with his research results may be well worth one’s while, opening up new contexts—of course, without the intrinsic association between liberation and penalisation, idealisation and delimitation, so typical for modern times.

Risk—During a period in which both the production of and discourse on contemporary art are permeated by re-feudalisation and eventisation, and in which the important questions of negotiation about the status of contemporary art are finally arriving at the point of debate, and where the establishment or the art market is already adequately supplied—precisely now it is important to embrace projects like that of Friedl Kubelka. Even giving the danger that some ending up—once again—at narrowing down the boundaries of institutions and the concept of art with a critical view. Yet if we venture an assertion, then perhaps we can recognise a dual sense of resistance that is not content with “common sense”. Instead, it repeatedly enables subversive thought and action, pushing through to new spaces in the process. This is a debate that touches on ideological issues. Let us pursue it!

Maren Lübbke-Tidow

¹ Many thanks to Daniel Baumann for the information and discussions.

Acknowledgement: Alassane Seck (Atelier d’Expression de la Clinique psychiatrique Moussa Diop – Centre Hospitalier National Universitaire de FANN – Dakar – Sénégal), Tapha (Moustapha Sy), Papis (Babacar Gaye), Ousmane Diop, gan-Jah (Ndiaga Ndiaye), Sidibé, Omar Ndiaye, Djim/Salamon (Abdoul Aziz), Charles Njaay, Tall, Faka, Docteur Manchita Gaye (DMG), Georg Gröller, Gudrun Schreiber (Kunstsektion, BKA), Karin Zimmer (Kunstsektion BKA), Gunn Pöllnitz, Fritz Panzer, Salvatore Viviano, Ibou Ba.

The exhibition is accompanied by an eponymous publication released by the Edition Camera Austria.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.