Press information

Mladen Bizumic / Sophie Thun

Interiors of Photography

Infos

Press preview with the artists

14.6.2019, 11 am

Opening

14.6..2019, 7 pm

Duration

15.6. – 25.8.2019

Opening hours

Tue – Sun, 10 am to 5 pm

Curated by

Reinhard Braun

Press downloads

Press Information

Getting into photography always also means getting into an elaborate apparatus, a widely sprawling dispositif, a kind of machine, but which one? Into the technological machine, the cultural one, the body machine, the desiring machine, the machine of fixing and classifying, into the artistic, aesthetic, scientific machine, the machine for the production of subjectivities and identities, or into the historical machine (to name just a few), which in different ways, by different strategies, can be brought to light, applied, reflected on, suppressed, liberated, or criticized? Félix Guattari proposed seeing machines as interfaces in order to counteract their foreignness—and in order to get over the fascination with technology and the humiliating form it sometimes adopts, we have to reconceptualize the machine.

Another proposal sounds considerably simpler: “You press the button, we do the rest.” The Kodak company long tried to keep us out of the complicated interplay of technology and culture; it left us entirely to our gaze, to our own desire to record, remember, and pass on, to our innocent instrumentalizing of representation, all quotidian, all culture. The technology is shifted to the other side of life, becomes invisible and inaccessible like nature itself. Yet suddenly a profound change begins to emerge in this industrialized nature of photographic representation; the analogue age moves toward its end. The technical, cultural machines, even the desiring machines, have a history, too, and it marches on.

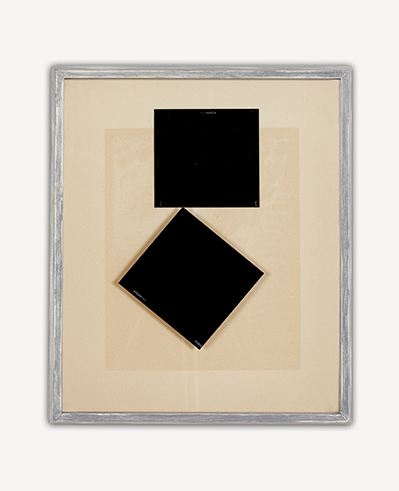

In recent years, Mladen Bizumic has been intensely studying Kodak’s company history in detail. Founded in 1880 by George Eastman, Kodak has had a decisive influence on the collective visual memory since that time; in the U. S., people spoke of a “Kodak moment” when a private event was felt to be important enough to be recorded for posterity. In 1976, Kodak reached a market share of ninety percent in the photographic film sector in the United States. The year before that, the engineer Steven Sasson had built the first digital camera for Kodak, but the company’s board refused to develop that prototype into a marketable product for fear of risking its profits from film. The inexorable decline began in the 1990s; finally, in 2012 the company had to declare bankruptcy. “Kodak Employed 140,000 People. Instagram 13” from 2017 is one of the works that Bizumic dedicated to the “phenomenon” of Kodak and its disappearance. Around 500 film canisters are distributed across the walls of the exhibition in a grid of several rows. Within this grid, other works are placed: “The Picture Made after the Last Picture” (2016), “Kodak (Presence)” (2014), “Kodak (Rolls)” (2014), and, among others, “One Second after the Digital Turn” (2003–16), consisting of a negative mounted on a matte analogue print, mounted in turn on a larger glossy print. Everything here is analogue; Bizumic works largely with analogue means, and with Kodak film more or less from the beginning. The film canisters, the packaging boxes, the negatives, the prints—the entire materiality of the age of analogue photography is present, arranged, mounted, reorganized. Strips of negatives are applied to the wall; plastic film canisters stand on frames; it is a unique world of handling, examining, selecting, enlarging. “Kodak (One and Three Images)” of 2015 shows nine prints from a roll of film that the artist forgot in a bag for a long time: strangely violet, a tree in various views from below, as if the shutter release had been pressed at random; the tenth “image” contains the corresponding slides including their frames as well as a USB stick, on which, perhaps, the data from the same images is located. The digital literally appears enframed by the analogue for the last time, strange among all these (still) familiar photographic materials and their aesthetic properties.

Yet Bizumic is not presenting a nostalgic look back or a romantic swansong. It is a (by all means conceptual) look at something we are accustomed to call a paradigm shift. It is about the transition from the industrial to a postindustrial age, an age in which production and information are merging, when work and time are becoming fluid, of the informal, of representation becoming fluid as well. What Kodak needed 140,000 employees for, Instagram managed to achieve, more than three decades later, with just thirteen, yet probably already with greater reach. But what does that mean for the photographs themselves? Bizumic asks what photography can be, what it was, and what it will be. In doing so, he makes use of a conceptual experimentation that requests analogue material as its base, nesting and reassembling its diverse material aspects, the unrepeatability of its results, the resistance of the material and of its qualities, its use in everyday culture, and the “naturalization” that this specific materiality experienced over the course of 150 years—and the latent anachronism that begins to cling to all that. But what does this mean for the history of the construction of a view, of a perception, and of an interpretation of the world? It would be a mistake to assume that Bizumic is suggesting in his works revolving around the “phenomenon” of Kodak that within the analogue world of photography this view, this perception, and this interpretation would have been less artificial, less constructed or produced. On the contrary, Bizumic works out for us the history of the constructedness of perception and representation: a history in which representation, photographic images, have always already been part of a complex dispositif, artificial and produced, within which the perceived world and the perceiving world constantly reshape, supplement, contradict, reinterpret, and update each other reciprocally. In a certain way, Bizumic takes on the challenging task of reconceptualizing for us one photographic from the viewpoint of another photographic.

In a very different but not necessarily contradictory way, the work of Sophie Thun also leads to the interior of the photographic in order to reconceptualize it. However, her point of departure—to return to the metaphor of the machine—lies in the realm of the photographic production of bodies—of images of bodies and gender. In a certain sense, Thun illustrates for us that the photographic has an extraordinary (but not coincidental) interest in the female body, in the flesh of the female body.

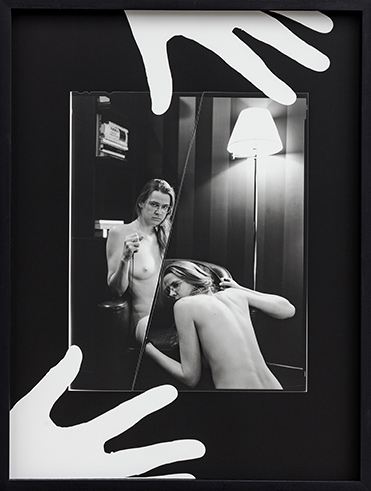

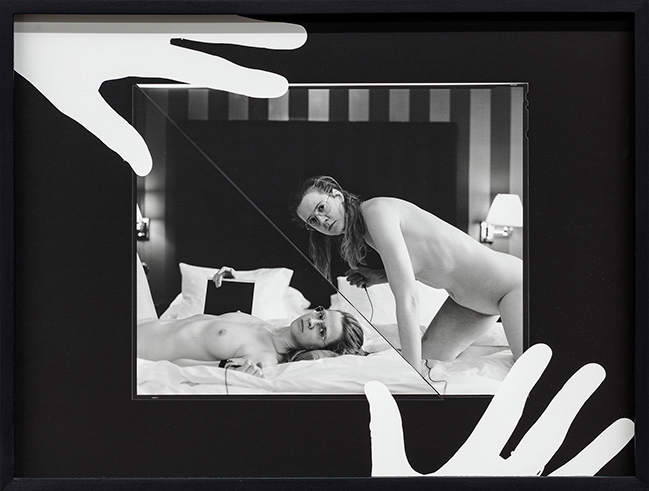

In her current work, “After Hours” (2019), produced in various hotel rooms after commissioned works or productions for other artists, we see the artist in small-format black-and-white prints (also analogue) in various poses in the bathroom, on the bed, in the bathtub—and always doubled. With a self-trigger in her hand, she “portrays” herself in poses, some of which refer to motifs from art history, that is, to a history of the depiction of the (nude) female body. But she cuts the negatives from two photographs diagonally before printing them so that their (halved) poses refer to each other in the finished, montaged print. The sexual connotations are obvious: the artist bends over her own naked body or kneels before it; in both cases, she is looking into the camera in order to make it clear that this arrangement inverts the history of being grasped by a gaze and a representation, that these montages are staged in view of the camera and for the camera. It is, not only because of the complicated type of montage of the negative, an offensive reconstruction of an image that in parts nevertheless reveals connections to a visual history. “It is necessary then to give oneself ‘experimental conditions’ in order to show [. . .] the incompleteness, the ‘contradictory,’ conflicting, incomplete nature—of all historical metamorphosis,” writes Georges Didi-Huberman. Sophie Thun creates her own experimental conditions that point to the overdeterminated character of the history of the representation of women in history of art. In one photograph in this series she is seen both naked and crouching next to her view camera holding the shutter release and a sheet-film holder. This pose refers to the Hellenistic Crouching Venus, who is surprised while bathing. The motif can be traced forward to Rubens; it depicts a moment at which a (strange, male?) gaze takes hold of the naked female body. The Hellenistic sculpture is a kind of proto-photographic sculpture, a snapshot of a moment turned to stone, in which a regime of the gaze is manifested and established, which would not release the female body from its power for the next two thousand years. In Sophie Thun’s work, however, it is not the shy, timed, or surprised gaze of Venus but the self-confident gaze of the artist who is resisting this regime of the gaze, in that it is her gaze that sets the scene in motion, her challenge to a regime of the gaze that produced the images, her agency that is translated into an image, her image.

In many of her works, the artist inscribes herself into photography in this form she has chosen herself. One can no longer speak of being captured by the images but rather of setting a photographic process in motion that finds its point of departure in the experimental disposition of the artist herself. Nearly life-size portraits showing Thun with the shutter release in her hand are combined with a photogram of her also nearly life-size body with the camera’s shutter release in her other hand on a single print, which the artist in turn holds in both hands and makes another self-portrait, next to which the photogram is illustrated in the same room; all of this is hung together on six large-format rolls of photographic paper on the wall of the exhibition space in which she took the photographs (“While holding (passage closed) (Y110,8M17,4D+59F8m18,142CA3T69,2b100l240),” 2018). Here the reconceptualization of the photographic machine reaches the limits of the ability to describe it.

Perhaps it is the multiplication of orders of representation, like the aforementioned cutting of negatives, which makes an unambiguous “place,” an unambiguous surface on which the meaning could come together, seem impossible. Where does representation occur, and when? How do different forms of representation refer to one another? Do we see in this layering of photographic elements a body, a subjectivity, an identity that does not want to be localized in the space of photography, not on this ONE surface, but rather escapes such fixing, that presents and exposes itself, but in the process replicates itself, splits itself, at once evading the representation and offering itself to it?

In this exhibition we see two artistic positions that, in different ways and from two different perspectives, work away at the dispositif of photography, work through the photographic, up to a point where the question of representation (representation of what?) becomes almost indistinguishable. Both positions destabilize our certainties about photographic images, how they are made, what we can see in them and why, and what we can know about them. Is it really primarily about the Kodak company, or is it rather about a (historical—that is, made, produced, and established) paradigm, which is supposed to determine which images we regard as images of this our world and the way that they refer to it? But could one not say exactly the same about Sophie Thun’s works as well? Is it for her about a way of inscribing herself into the medium of photography, or is it not rather much more about how we are already caught up in the layers of this form of representation and wander almost inextricably between its surfaces, like ghosts trying to work their way through the layers of images but without reaching that one surface on which we could find ourselves again? Does not Mladen Bizumic, too, describe this phantasm in his Kodak series, seemingly having found a place or a moment—the “Kodak moment”—at which life condenses in a way in order to want to become an image, to have to become one? Which mechanisms foster which photographic images, which rebellion or which subjugation—which appropriation or which rejection, which knowledge about the history of images or which ignorance about their history leads to which production of images? But the photographic, it reveals itself as that intersection at which these moments of knowledge, experience, history, research, resistance come together in order to modify a complex machine—a machine that photography has always already been.

Reinhard Braun

Mladen Bizumic, born 1976, lives and works in Vienna (AT) and Auckland (NZ). He studied cultural studies at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and fine arts at the University of Auckland. By working predominantly with photography, Bizumic makes installations that appear like sites or scenes that await the event of their occurrence. There is constant tension between the works and their display. Selected exhibitions: Leopold Museum, Vienna; George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York (US); Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf (DE); MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, Vienna; the 10th Istanbul Biennial (TR); the 9th Lyon Biennial (FR); the 3rd Vienna Biennale; Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw (PL); the 1st Auckland Triennial (NZ).

Sophie Thun, born 1985, is an artist based in Vienna (AT). Her complex photographic interventions explore the construction of the self in the conflicted space of representation. She is board member of the hackerspace Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory and member of the artist collective <dienstag abend>. In the context of the 58th Venice Biennale, Thun is part of the project “images of / off images” for the Austrian Pavilion. Her work has recently been shown at Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna; Austrian Cultural Forum in Berlin (DE); Kunstraum München, Munich (DE); during Les Rencontres d’Arles, Arles (FR); ICA Yerevan (AM); New Jörg, Vienna.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.