Press information

Sculpture

Infos

Opening

6.12.2013, 8 pm

within the scope of CMRK

Exhibition talk

with the artists present

7.12.2013, 1 pm

Duration

7.12.2013 – 16.2.2014

With

Laurie Kang (CA), Kasia Klimpel (PL/NL), Lotte Lyon (AT), Christian Mayer (AT), Peter Puklus (HU), Carly Steward (US), Michael Strasser (AT), Anita Witek (AT)

Opening hours

Tue – Sun 10 am – 5 pm

One Thursday each month the exhibition stays open until 9 pm

12. 12. 2013

16. 1. 2014

13. 2. 2014

Press downloads

Press Information

Sculpture Cutting, layering, rolling, folding; interventions in different developmental processes; models, dummies, books, object ensembles, relicts—from all sides the question of photography as material and body is addressed, as is its intervolvement with the world of things, with what is real, with the sculptural. Yet it is not the relation between image and reality that is up for discussion here, nor the question of representation—the confrontation of object and image is more a collision than representation, with materials, and bodies, colliding with visual aspects or with knowledge, though with something remaining behind that oscillates between image and object. This material aspect within photographic practices is referenced by the term “sculpture”, whereby photography as a practice of handling the tangible is moved to the forefront. On the one hand, the photographic act itself nearly becomes a manner of sculpture, with the visual aspects shifting into the material ones. On the other, divergent things crowd together to create a sculptural form, or are translated into a form that actually only exists within and through photographic methods. So words like collision and confrontation signify an actual interest in these forms of pictorial materialisation and in pictures as a form of materialisation. They mark the moment in which image production collides with the visible and the tangible. This forceful encounter of object, image, and meaning does not pass off without sacrifices, distortions, illusions, and erroneous assumptions. Against this background, photography is not a field of conciliation, but a field of conflict, encroachment, and confliction where bodies and materials clash and linger behind. Through this clash it becomes clear that we may indeed still speak of a (partially) material culture, despite all of the virtualisation of visual relations and of the social realm, as has increasingly become established in recent decades.

Laurie Kang

The works called “Untitled” are composed of lengths of photographic paper that are affixed directly to the wall on one end, with the edges tilting forward and the paper rolling up as it reaches the floor. Here the artist has used Kodak Endura glossy chromogenic paper with a width of 50 inches. In the 1950s, the “C-type” was the first chromogenic paper to be introduced, and since then the designation “Type-C-print” or “C-print” has become the standard term used for colour prints. Laurie Kang (born 1985 in Toronto) is thus putting on exhibit one of the most important materials of contemporary, twentieth-century photo production. In her work, which eschews simple labelling as photograph, collage, sculpture, or installation, she frequently blurs the boundary between image and object. An example of this is her “Parallelogram Studies”—montages of cut or torn-apart photo paper. It is as if we were being presented with the primordial emptiness that has become inscribed in realities since the inception of photography. Yet precisely this makes it clear how these inscriptions have, from the outset, likewise been reliant on material carriers that move to the forefront here as an independent photographic element.

Kasia Klimpel

Spectacular skies, sunsets, landscape horizons, craggy mountains—what appear to be clichéd pictures from nature are in actuality photographs made in the studio. They show various arrangements of processed coloured paper, placed in layers, with photography first turning the renderings into something that can (or must?) be deemed nature. The works toy with our expectations of identifying images, ascribing meaning to them, and identifying them based on existing conventions of representation. In the process, Kasia Klimpel (born in Gliwice, lives and works in Basel and Amsterdam) reconstructs image templates, genres, and aesthetics that she has discovered online while researching pictures according to catchwords like “horizon” or “sunset”—her reconstructions themselves are thus founded on conventions of representation that she has adopted. Accordingly, Klimpel channels some of these would-be landscape pictures back onto the Internet by positioning her photographs at their respective geographic locations in Google Maps, where they can be viewed by users as a “representation” of this place (“The Grand Tour”, since 2011).

Lotte Lyon

Taking specially folded Japanese origami paper, the artist arranges various sheets in front of the camera—staged to resemble architectures or minimalist spatial installations “Untitled” (2012). Lotte Lyon (lives and works in Vienna) is a sculptor who extends her reduced, geometric sculptural works into the realm of photography. Precise spatial relations, shifts in function, and minimal colour coding of the objects or spaces all distinguish her strategy of dealing with tangible things. Such moments also emerge in Lyon’s photographs: a Japanese hotel towel becomes a serial sculpture in a new work of art “Untitled (Tenugui)” (2013), with both its materiality and its original utilisation context remaining unclear. It is along this margin of the identifiable, of oscillation between various possible designations, of uncertain scale that Lotte Lyon develops both her installations and photographs.

Christian Mayer

Some works created in recent years by Christian Mayer (born 1976 in Sigmaringen, lives and works in Vienna) explore questions of preservation in view of attempts to project cultural values into the future. In this sense, photographic methods and materials continue to play a role in Mayer’s work: “Through Historic Hole in the Rock Mormons Blasted a Path to Their Promised Land” (2011) presents a blown-up picture that was taken in 1949 during an expedition in Utah. The landscape itself ended up being named after the film used: ̔“Kodachrome Flat”. The history of visualisation and archivisation of reality is also linked to a history of certain film material, its possibilities and its manipulations. The same applies to the series “Silene” (2012): It is a group of three large-scale photographs of plant seeds that had been preserved for 30,000 years in Russian permafrost soil before being discovered by scientists in 2011. The three prints, which were produced using the dye-transfer method, are each lacking one of the three primary colours, causing them to radiate in red, yellow, and blue. These works, which essentially thematise the cultural technique of preservation, likewise touch on how archivisation is dependent on techniques of representation and its potentialities, but also on the limitations inherent to recording a material culture.

Peter Puklus

The publication Handbook to the Stars (2012) takes up a tableau-like arrangement of photographs that, page by page, have been tactually scrutinised, so to speak, and translated into book form. This process causes gaps to arise on the book pages and many pictures to be truncated, which are then to be found somewhere else in the book in full form. By reversing this process, Peter Puklus (born 1980, lives and works in Budapest) develops a wall installation with thirty-two books is created. Notable is how this installation not only falls back on a manifold translation of photographic images; indeed, it is the pictures themselves that also fall back on previously designed settings, models, collages, and spatial constructions. Almost no elements are found subjects, with nearly everything specifically arranged for the camera. The book thus primarily documents this treatment of materials, objects, spaces, and geometries. Even the book itself is translated in the process into an independent format of presentation that contrasts with the usual circulation, handling, and interpretive approach. It is this transition from book to installation, preceded by the transition from photography to book page, that always also expresses a transformation of the materiality of representation.

Carly Steward

In her “Museum Displays ”, Carly Steward (born 1979 in Redlands, California, lives and works in Los Angeles) arranges objects that are used by museums to present exhibits—uniquely shaped metal objects whose function and utilisation context are not readily apparent upon first glance. These are things that serve to facilitate the staging of displays and the spatial dramaturgy of aesthetics and knowledge; however, when robbed of this function, they also start to lead an independent existence as mysterious objects that are first and foremost distinguished by the fact that something is missing. The “collages” (2013), in turn, are created based on an overworking of photo books. Incisions, cutting out image content, misshaping, and the recomposition of parts all engender a sculpture whose basic conditions mostly elude comprehension, except perhaps in the identification of representational fragments on the surface. The practice of photography-related appropriation and (visual) adjustment (of landscape, for instance) is, in this radical practice of material conversion, doubled and rescinded at the same time. Here photography is literally understood to be a material that can be reshaped, deformed, and transmuted into something entirely different.

Michael Strasser

For the project “Solitaire” (2012), the artist Michael Strasser (born 1977 in Innsbruck, lives and works in Vienna) refashioned an old farmhouse into a kind of sculpture between June and September 2012. The house is located in the Slovenian town of Serdica, and had been deserted for thirty years. All material from the original building was removed down to its foundations and then newly installed. The clearing out, uncovering, and removal of the nearly one-hundred-year-old building, piece by piece, was predominately designed to offer insight into the history of this site and its onetime residents. Numerous details of this work were documented and annotated, while found objects were archived. The disappearance of the space in its sociohistorical sense corresponds with a fragmentary reconstruction of its history. Here Strasser is fascinated by the idea of “anthropological space” and by the correlation between the materiality of the space and its construction as habitat, through which this space also assumes a form of representation that is utterly altered by the artist’s intervention.

Anita Witek

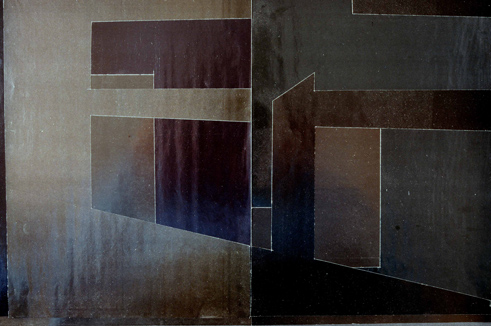

Employing various photographic templates, usually books on architecture, Anita Witek (lives and works in Vienna) cuts out motifs so that only the edges of the pictures remain. These (abstract) photographic “leftovers” are arranged and layered, with this process of superimposition then photographed in all its different stages. The photo series that thus emerge trace this process, whereby the constellation of flat surfaces and cropped edges becomes ever more complex, with some parts disappearing, being covered by others. Sometimes even seemingly architectural “spaces” take form, which are then suddenly deconstructed and appear to implode. The photographs are status descriptions of this procedure; they show a momentary excerpt of a material process that may potentially never reach conclusion or that is at danger of disappearing into a kind of visual entropy. In this respect, these series present what might be called sculptural work with photographic material whose iconic content is transformed into a reification of the tangible.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.