Camera Austria International

114 | 2011

Über das Dokumentarische als politische Praxis / On the Documentary as Political Practice.

Gastredakteur / Guest-editor: Tobias Zielony

- REINHARD BRAUN, MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, TOBIAS ZIELONY

Tobias Zielony: I Don’t Believe They Will Disappear … - TOBIAS ZIELONY

- REINHARD BRAUN, AHLAM SHIBLI

Ahlam Shibli: Objecting to Imposed Invisibility - REINHARD BRAUN, DAVID GOLDBLATT

David Goldblatt: Looking at Our Structures - MAREN LÜBBKE-TIDOW, MICHAEL SCHMIDT

Michael Schmidt: Asking Questions rather than Giving Answers - REINHARD BRAUN, HITO STEYERL

Hito Steyerl: Documentary Practice Is Always Already an Action - REINHARD BRAUN, JO RACTLIFFE

Jo Ractliffe: A Space for Other Images - SUSANNE HOLSCHBACH, PEGGY BUTH

Peggy Buth: Truth Always Also Has the Structure of Fiction

- JAN WENZEL, ALEXANDER KLUGE

Alexander Kluge: Gabi Teichert at the Party Confernce of the Social Democratic Party of Germany - TOBIAS ZIELONY, PAUL GRAHAM

Paul Graham: Reframing the Question "How Is the World?" - TOBIAS ZIELONY, LAURENCE BONVIN

Laurence Bonvin: Living Ghost Towns - WOLFGANG TILLMANS, MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW

Wolfgang Tillmanns: Finding Warmth in This Coldness is the Prop for My New Photos - MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, PHILIP-LORCA DICORCIA

Philip-Lorca diCorcia: Since I've Never Told the Truth I Can't Tell a Lie - HELGARD HAUG, DANIEL WETZEL

Rimini Protokoll: Because the Reality of the Encounters Always Newly Overwrites - MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, RUTI SELA & MAYAAN AMIR

Ruti Sela & Mayaan Amir: Triggering the production of Ideological Positions - MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, RENZO MARTENS

Renzo Martens: We Don't Actually Know What We're Seeing

- TOBIAS ZIELONY, THOMAS RUFF

Thomas Ruff: Optical Prostheses - TOBIAS ZIELONY, TIMM RAUTERT

Timm Rautert: Participative Interest - KIRSTY BELL, COLLIER SCHORR

Collier Schorr: The Regularity of Difference - TOBIAS ZIELONY, UCHIHARA YASUHIKO

Uchihara Yasuhiko: The Untaken Photos - SABINE SPILLES, LARRY FINK

Larry Fink: The Notion of Empathy - WALID SADEK

A Time to See 2/4 The Present of Seeing Eyes

Preface

Camera Austria International 114 | 2011

Preface

For this edition we invited th e photo artist Tobias Zielony to explore the question of the documentary as political practice with us as guest editor. The world seems to have become photographic, but “the more uninhibited its distribution, the more manifold its forms, the more powerful its effect, the more the image is, the images are, suspected of being deceptive” (Jean-Luc Nancy). What does this suspicion mean for the idea that images could propose a different space of the social and the political, which does not merely promote a penchant for the sensational and for disasters, but which also enables an eventfulness of the image, which undermines the predominant conventions of representation and represses the chattering spectres of mass media? Perhaps it is therefore more necessary than ever to ask about the current strategies of contemporary photo artists and filmmakers, who still remain orientated to specific social realities that still seem to be based on a concept or a notion of the documentary and that could still open up a different space for image politics. We pursued these questions in 20 short interviews with international photo artists and filmmakers, thus highlighting different documentary approaches, which we pose for negotiation at the same time, as the actualisation of a critical debate about the documentary in the field of the visual itself. “Following the ‘return of the real’, which was already stated for the 1990s, it seems that it is time to pose the question of the critique of representation anew” (Susanne Holschbach in conversation with the artist Peggy Buth).

In his own artistic work Tobias Zielony, with whom we developed the questions of this edition together along with the selection of artistic positions assembled here, always links social reality with spaces and actors, i.e. with the fields of agency of social individuals. But which image does his documentary practice then draw of these social individuals, with whom he—temporarily—shares a common space? Tobias Zielony has become well known in recent years with series about young people from Europe and the US; his pictures exemplify questioning the subject production of documentary photographic images, questioning w hat photography still does with the people it depicts. In March this year we had a discussion with Tobias Zielony about these and other questions, of which excerpts are published here along with a selection from the current series “Manitoba” (2009), which will be shown in the Camera Austria exhibition rooms in a solo show beginning in July 2011.

The focus of this issue is expanded with the second part of the column by Walid Sadek: “The Present of Seeing Eyes” as a reflection on the appropriation of the body by seeing, which in the moment of death turns out to be the exhausted temporality of seeing. Reading this together with the documentary results in questions about duration, the gaze and bodies, and on seeing as a social practice.

The many different and international voices that speak up here have led us to postpone the planned Forum until the next issue. However, we have taken this special and polyphonic issue of Camera Austria International as an occasion to offer you an expanded distribution, so that you can now obtain our magazine from over 700 further sales locations in addition to specialised bookshops. We would also be very pleased to be able to meet you in person at our fair booth at Art Basel.

Maren Lübbke-Tidow, Reinhard Braun, Tobias Zielony

June 2011

Entries

-

REINHARD BRAUN, MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, TOBIAS ZIELONY

Tobias Zielony: I Don’t Believe They Will Disappear …

Q It has become evident in our conversation that your work moves on the border between the documentary and a moment of fictionalisation. What does that mean for our theme of the documentary as political practice—in light of the total visual penetration of our political-social present, in which image and reality permanently seem to be mutually setting up and commenting on one another?

A I think the work functions because this moment of the photographical is still perceived. Even if people no longer firmly believe in it, there is still this assumption in their minds that a photo exhibits a reference to reality, to the place and the point in time when the photo was made. Of course, it may be that this wears down over the course of time, due to more and more staged images, manipulated images. However, I have not yet entirely given up this hope. From the beginning, photography has always been a convention between the producer and the viewer. If you look at the images from Libya or Egypt, naturally you can doubt all these images, why they were made, with which intention, whether they are genuine or not; what does genuine even mean? So the way in which these images are worked with, where they show up, which political developments they trigger, always still has a crucial significance. We must let go of the idea of objectivity once and for all. The conventions will change, but I don’t believe they will disappear.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 11–18.

-

-

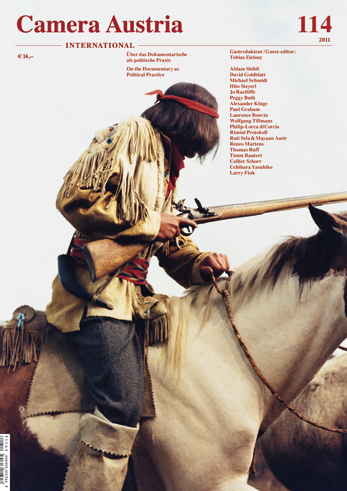

TOBIAS ZIELONY

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 11–18.

Tobias Zielony, Chronic. Aus der Serie / From the series: Manitoba, Winnipeg, CAN, 2009. -

TOBIAS ZIELONY

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 11–18.

Tobias Zielony, Powwow. Aus der Serie / From the series: Manitoba, Winnipeg, CAN, 2009. -

TOBIAS ZIELONY

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 11–18.

Tobias Zielony, Ghost. Aus der Serie / From the series: Manitoba, Winnipeg, CAN, 2009. -

TOBIAS ZIELONY

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 11–18.

Tobias Zielony, Greenwich. Aus der Serie / From the series: Manitoba, Winnipeg, CAN, 2009.

-

-

-

REINHARD BRAUN, AHLAM SHIBLI

Ahlam Shibli: Objecting to Imposed Invisibility

Q We’d like to come back to one point you mentioned as the possible effect in a struggle that your images might have and the refusal to identify and to package the visible for further use: how is it possible to keep the images open to different further “uses”? Do you feel that there are different addressees: actors in the political field, the people that struggle for their wishes and expectations, and finally something like “the art field”? Don’t the images have different effects in these different fields of reception?

A The work is not made for any specific group of addressees; it is virtually impossible and actually not desirable to control who will be addressed in which way by any one of the works. Maybe it is even a bad idea, for instance, to try to separate actors in the political field from people who go to an art space/museum to see an exhibition or who leaf through a book. Would a person involved in a political struggle be prohibited from visiting an art space/museum, would an art space/museum-goer be prohibited from finding support for their political involvement in the art they see?

Nevertheless, it may also be said that the most satisfying reception of certain works has been by the people directly concerned: the orphans who saw “Dom Dziecka. The house starves when you are away” (Poland, 2008), the refugees who saw “Arab al-Sbaih” (Jordan, 2007), the immigrant care workers and their employers who saw “Dependence” (Barcelona, Spain, 2007), the people who suffered the German occupation and the people who suffered the French colonial wars “Trauma” (Corrèze, France, 2008–09). The work should be accepted as it has been constructed—fulfilling the need to show what is forbidden to be seen and resenting reification and commodification of what is shown—so the notion of “using” the work in any way is alien to its reality.Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 19–20.

-

Ahlam Shibli: Objecting to Imposed Invisibility

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 19–20.

Ahlam Shibli, Untitled (Trauma No. 28), Corrèze, France, 2008–09.

C-print, 57,7 cm × 38 cm.

-

-

-

REINHARD BRAUN, DAVID GOLDBLATT

David Goldblatt: Looking at Our Structures

Traditional Beehive Hut, KwaCeza, KwaZulu, July 31, 1989.

The home of Mildred Nene, two unmarried daughters, their three children and three other grandchildren. The hut took two month to build in 1987 from wood and grass brought on heads by the three women. At 59 Nene did not qualify for a pension. Sometimes one of her seven children or the father of one of her grandchildren would send money. There was no other income. Adjacent to the hut was a rectangular room with a steel roof, the house of her son Isaac who worked in Durban and who came home for annual holidays. He sent her no money but would bring somethings on these visits. Near the hut was a byre for Isaac’s two cows. Nene had some goats but they were stolen. She knew who took them but thought it best to keep quiet. People do not help each other, she said. The chief helps according to the size of the gift one gives him. Isaac sometimes wrote to her. What about? His chest, which gives him trouble. When asked if she ever wrote to him, she replied, “He knows my life. I can’t tell him anything.”

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 21–22.

-

David Goldblatt: Looking at Our Structures

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 21–22.

David Goldblatt, In the home of Mildred Nene, a beehive dwelling that she and her two daughters built at KwaCeza, KwaZulu. 31 July 1989.

-

-

-

MAREN LÜBBKE-TIDOW, MICHAEL SCHMIDT

Michael Schmidt: Asking Questions rather than Giving Answers

Q How do you approach your themes or subjects? Are there images first that call for an order and form a theme in the process of editing, or is there conversely a theme that you want to work on and that steers the process of shooting, to a certain extent?

A It is more complex and ultimately a conglomeration of all of that; but the theme is there first, although even the best theme is of no use, if the aspect of renewal is not inherent to the image. But in the end, content determines the form.

Q History or historical connections are constantly present in many of your works—but without giving the impression that something is systematically worked through here. On the contrary: history meanders through your images, connections open up more from the personal experiences or associations of each viewer. So history is made productive here as something that is not closed and cannot be closed. How would you describe the way you deal with history?

A But ultimately, that is in fact my system, to see history as open and uncompletable, to keep it alive. Asking more questions than giving answers.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 23–26.

-

Michael Schmidt: Asking Questions rather than Giving Answers

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 23–26.

Michael Schmidt, Meer #3, 2007. Silbergelatine-print, 49,5 cm × 65 cm.

-

-

-

REINHARD BRAUN, HITO STEYERL

Hito Steyerl: Documentary Practice Is Always Already an Action

In one of my most recent works, I highlighted the copyright marks from WWII photographs sold on eBay. The pictures were made by German soldiers on the Eastern front and show all sorts of war scenes. The more violent, the more expensive the photos are. eBay vendors add copyright signs to affirm their property rights, and also to cover representations of war crimes, swastikas and other illegal content. In my work, I’ve subtracted the photographic images and left the copyright marks as they were. They represent the original photographic picture seen from the angle of their existence as digital commodities. This is their contemporary form of circulation and movement. Yet, in a negative and subtractive way they retain the traces of the resistance of the persons originally shown in the pictures, mostly captured female Soviet soldiers, who were fighting against the Nazi invasion. Those women constituted one of the groups who were to be immediately killed after their capture; they had no chance of survival. So in some cases, a very abstract form of their negative imprint is preserved. These are their portraits in 2010, under the condition of digital capitalism, and I’d argue that these are documentary images, because they show the reality of the contemporary movement and dispersion of the original photographs.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 27–28.

-

Hito Steyerl: Documentary Practice Is Always Already an Action

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 27–28.

Hito Steyerl, Russische Kriegsgefangene Flintenweib (aukcia 270519641708). Aus der Serie / From the series: The War according to eBay, 2010.

Löschungen auf eBay-Foto / Deletions on eBay-photo. C-print, 100 cm × 150 cm, Leuchtkasten / light box.

-

-

-

REINHARD BRAUN, JO RACTLIFFE

Jo Ractliffe: A Space for Other Images

Q In your photographs you are repeatedly concerned with landscape and its role in the (South African) imaginary, especially in relation to the violent legacy of apartheid. Your “idyllic” pictures often turn out to be settings of historical violence and annihilation, they refer to traumatic events that are essentially unrepresentable and cannot be reduced to depictable elements of reality. At the same time, you have stated your interest in what is fleeting, ephemeral: an interest in the revelation of absence. Your work could thus be read as a query of the ambivalence of photographic representation: with the doubts about the possibility and appropriateness of visualising war, violence and power, another possibility of photography is brought into play at the same time, that of producing meanings that do not primarily have to do with the reality or the authenticity of the depictions. What happens then between image and reality that could open up an option like this? And what does this question mean for your photographic practice; which strategies do you use when you want to “elicit the real”—like the title of your seminar at the Salzburg Summer Academy this year?

A I think your reading of my work as “a query of the ambivalence of photographic representation” is very well put. And whatever my thematic concerns, it has been a constant preoccupation always. It’s also one that is inextricably bound up in a conviction that photography, more than what it may depict, is about “seeing”—and by this I mean a “seeing” that reflects as much upon conditions of perception as it does the thing photographed.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 29–31.

-

Jo Ractliffe: A Space for Other Images

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 29–31.

Doppelseite / spread: Jo Ractliffe, S. / pp. 30–31.

-

-

-

SUSANNE HOLSCHBACH, PEGGY BUTH

Peggy Buth: Truth Always Also Has the Structure of Fiction

B Positing the question of the documentary as political practice provokes me to contradict, even though I certainly feel connected to the context of the issue.

Why should artistic practice—I presume that the documentary also means a specific artistic practice here—subordinate itself to this claim? Or conversely, can it even claim for itself to be political agency?

In the question I recognise a desire, with which I can identify: the wish for societal efficacy, the urgency of taking action in the face of social and political developments. I also see the ongoing engagement with the notion of an “immediacy of photography” in this context, or a direct inscription of reality, as it is found in the various discourses of documentarism. A critical potential is associated with this, which seeks to situate authenticity, witness and truth as force fields of enlightenment and the integration of so-called “bare life” in the areas of political life—which I find comprehensible, but still problematic.H I would absolutely agree with your analysis and with your unease. The documentary, as I also understand the thematic framing of this issue, can no longer retreat behind its critique, in other words behind the deconstruction that its implicit preconditions and presuppositions already went through in the 1970s and 1980s. One could speak of a post-documentary condition—a suggestion that aims exactly at the problems that this allusion evokes. Following Douglas Crimp’s distinction between an affirmative and a resistive understanding of postmodernism, I still tend to see a critical (post-) documentary practice in taking a reflective stance with respect to its preconditions. Following the “return of the real”, which was already stated for the 1990s, it seems to me that it is time to pose the question of the critique of representation anew. I see your work against this horizon as well.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 32–34.

-

Peggy Buth: Truth Always Also Has the Structure of Fiction

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 32–34.

Peggy Buth, Gene Autry, ca. / about 1957.

Filmstill aus der Serie / from the series: Who is telling the story? Seit / Since 2009.

-

-

-

JAN WENZEL, ALEXANDER KLUGE

Alexander Kluge: Gabi Teichert at the Party Confernce of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

Films about party conferences have been points of crystallisation in the history of the documentary several times—this is true not only for the aggressive self-representations of a National-Socialist ruling elite in Leni Riefenstahl’s films of the Nuremberg Rallies (1933–35), but also for the films that directly contributed to the prevalence of the Direct Cinema method in the 1960s: in the US “Primary” by Albert Maysles, D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock (1960); in Germany “Parteitag 64” by Klaus Wildenhahn. Alexander Kluge also demonstrated his approach of creating mixed forms from the fictional and the documentary especially impressively in the party conference scenes of the film “The Patriotic Woman”, in which he expanded an actual event with a fictive situation: the protagonist of the film, the history teacher Gabi Teichert, played by Hannelore Hoger, visits a party conference of the SPD.

A Scene from the Film “The Patriotic Woman” (1978)

Gabi Teichert comes up the steps to the party conference of the Social Democratic Party of Germany . Original sound, off.

Gabi Teichert sits in the assembly.

Commentary: Since Gabi Teichert teaches history, she wants to take a practical part in the decisions about this history. She must attempt to make an impression on the delegates of this event.[…]

Delegate, Ms. Teichert.

The delegate is not yet convinced.

Gabi Teichert: I would like to come back again to the core of my views. The source material for teaching history at secondary schools is not worth disseminating. Not because there was no eventful German history, but because it was so eventful that it cannot be processed in a positive sense.

Delegate: Well …

Gabi Teichert: … what it is that I have to work through, then you would also try to change history, to change it more than you have so far.

Delegate, doubtful.

Gabi Teichert: … that the final product of history is actually that which later becomes the source material for teaching history …Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 35–37.

-

Alexander Kluge: Gabi Teichert at the Party Confernce of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 35–37.

Alexander Kluge, Still aus / from: Die Patrioten, 1978.

-

-

-

TOBIAS ZIELONY, PAUL GRAHAM

Paul Graham: Reframing the Question "How Is the World?"

Q In your work there is a movement that links the question of how a (frequently disadvantaged) section of people in societies such as those of the US or Great Britain lives, with the question of the representability of this presumed reality using the means of photography. I am thinking here, for example, of the over-exposed, almost white pictures of unskilled labourers on their way to work in the rich, white suburban residential areas of the US in the series “American Night” (1998–2002). What does this link between social reality and the question of its representability mean for our idea of the political on the one hand and that of the documentary on the other? For a photographer, these questions are also raised concretely in practice: Where do I take photographs at all and why do I make a picture? And what happens when these pictures stand next to one another? In your work “A Shimmer of Possibility” (2004–06) you conjoin short sequences into miniature-like narratives. Between and next to the images, gaps of the untold, the possible break open. How did this work develop, and what does the title mean to you, which could be read as being quite hopeful, almost utopian?

A […] The styles may change, but the territory is as vital today as it was then, and the question remains, the very same question you are kind of asking me: how does the photographer today work with intelligently photographing life-as-it-is? With what fresh possibilities can you make photographs about this world, here, now? For the last two decades, the tide has moved against those who struggle with this issue, but that does not mean it is not vital in giving shape and form to our world. It is also, lest we forget, an artistic contribution of the highest order, for the simple fact that remains there is a profound creativity in those who with boldness, present new and sometime revelatory ways of reframing the question with which the best of photography has always been preoccupied: “How is the World?”

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 38–40.

-

Paul Graham: Reframing the Question "How Is the World?"

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 38–40.

Paul Graham, New Orleans. Aus der Serie / From the series: A Shimmer of Possibility, 2004–05.

-

-

-

TOBIAS ZIELONY, LAURENCE BONVIN

Laurence Bonvin: Living Ghost Towns

Q Let’s talk about your project “On the Edges of Paradise” (2005–06) on gated communities outside Istanbul. I am very interested in the idea of control. There seems to be a similarity to the camp-like settlement outside Cape Town. Both are gated, fenced in. When I look at your pictures from Madrid or Istanbul, I wonder why people don’t freak out, kill somebody. They are out there in the vastness of the landscape, at times very lonely. Maybe they need a fence around them as a measure of self-control?

A Inside the gated communities I often had a very strong feeling of unease, and not only because I was photographing there illegally. I would look outside a window and see a wall or a fence with barbed wire on top of it. This might make one feel protected, but I felt imprisoned. Why would people want to live like that? Why would they lock themselves in these anxiogenic spaces? There’s actually been quite a lot of fantasy around the gated community turning into a mad and violent place, such as in some of Ballard’s novels or a Mexican film called “La Zona” (2007, Regie: Rodrigo Plá). Gated communities and places like Blikkiesdorp are two sides of the same coin, they are places of confinement, which are about control and surveillance, either imposed on people by the government or chosen by people. They both reflect certain fears and the desire to control them.

Q Obviously both your subject and your way of working are related to the New Topographics movement. What I always loved about that kind of photography was that it had a very sober, non-ideological, non-romanticising view of landscape. But at the same time it created an almost fictional, film-like tension, as if something was about to happen. It seems that there is a contradiction between these two notions, let’s say the documentary on the one hand and the fictional on the other. Is this something you would see in your own work, too?

A Absolutely, but I don’t see a contradiction between these notions, rather a duality that creates a tension. The intensity of the tension between documentary and fiction, or between the factual and the metaphorical, the mundane and the political, is exactly what interests me in photography, in art, in cinema or in literature. It has to do with how to tell a story with what is there, existing, a story, in the broad sense, that connects with the world and raises questions.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 41–44.

-

Laurence Bonvin: Living Ghost Towns

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 41–44.

Laurence Bonvin, aus der Serie / from the series: Blikkiesdorp (Cape Town), 2009. Inkjet-print auf / on Dibond, 40 cm × 50 cm.

-

-

-

WOLFGANG TILLMANS, MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW

Wolfgang Tillmanns: Finding Warmth in This Coldness is the Prop for My New Photos

Q Your more recent photographic works, now also made with a digital camera, seem with their hyper-presence of the real to be virtually a counterpoint to the “abstract” works that you have increasingly brought into your exhibitions in the past few years. What motivated you as a photo artist to newly regulate this tension between reality and visibility again, to focus on motifs that are directly and concretely comprehensible and picture them—and specifically different from before, also to use a digital camera?

A Since I have been dealing with the photo as object for about ten years and tested possibilities for producing images without a lens—and since I treated my exploration of the political outside world primarily in the table installations “truth study center” (2005–07)—beginning in 2009, it seemed to me that it was urgently necessary to take the camera in hand again. To see what it can do. The deceleration that I attempted with the abstract images called for an opposite.

Digital imaging techniques are often used to twist reality, to depict something in a changed way. But I was never interested in this approach. Dali already painted melting clocks in the 1930s, there is no cognitive gain today from surrealist digital image processing, for instance. But the perception of the mutability of the digital image and the almost inevitable questioning of what is depicted in the digital photo, is driven primarily by a self-assessment of “Yes we can”. Because we can, we make stomachs slimmer in advertisements and make worlds more fantasy-like in artistic photography. For me, though, the world is already surprising enough, dissonant enough. I find the normal absurdity that already exists quite fascinating. It cannot be overtaken by any made-up ideas.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, p. 45–47.

-

Wolfgang Tillmanns: Finding Warmth in This Coldness is the Prop for My New Photos

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 45–47.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Tukan, 2010.

C-prints, verschiedene Größen / dimensions variable.

Courtesy: Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Köln, Berlin.

-

-

-

MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, PHILIP-LORCA DICORCIA

Philip-Lorca diCorcia: Since I've Never Told the Truth I Can't Tell a Lie

Q In your works, you maintain a very precise tension between document and staging, a strategy that counters the dogma of a merely presumed objectivity of the documentary with a moment of fictionalisation in a very expressive and exemplary way. In your pictures you bring these two poles of document and fiction together. This results in tableau-like images; we don’t know who the actors in your images are, how you work with them, in short: how the images are created. What drives you, what do you discover in reality, and which processes are set in motion when it comes to this moment, in which a situation is transposed into an image?

A It’s always remarkable how often certain words appear and reappear: the most mundane is “tableau”, a real signifier for quality photography because it seems so unphotographic, a link to the quality past, which stretches its seams to include illustration and narration, in order to stroke the insatiable desire for soap-operatic vicarious experience. Documentary photography delivers by the pound. It’s all about weight. Deliver the goods. Fiction is something you relate to when you wake up in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep. I have read many accounts of writer’s habits—getting up obscenely early to put in their quality time with the word processor: self flagellation with the emphasis on self. Photographers get up early to watch others flagellate themselves, emphasis on others. I am not really adept at either mode. Maybe the soggy ground I stand on, the mush described as a moment, is more interesting than the anchor grounded in the concrete that will never set under an ocean of bullshit.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 14/2011, pp. 48–49.

-

Philip-Lorca diCorcia: Since I've Never Told the Truth I Can't Tell a Lie

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 48–49.

Philip-Lorca diCorica, Untitled. Aus der Serie / From the series: East of Eden, 2007–08.

Inkjet-print, 101,6 cm × 152,4 cm.

Courtesy: David Zwirner, New York.

-

-

-

HELGARD HAUG, DANIEL WETZEL

Rimini Protokoll: Because the Reality of the Encounters Always Newly Overwrites

Ein Foto: Männer inmitten der Wertstoffe, die sie in der vorangegangenen Nacht aus dem Müll in den Straßen Istanbuls gesammelt haben. Vier von zehntausenden von Sammlern – vier von hunderten von Kurden aus dem gleichen Familienstamm, die aus Dörfern 20 Stunden östlich von Istanbul in die Stadt pendeln, wann immer die familiäre Situation es erlaubt und die Schulden es erzwingen. Hinten rechts: Die aus Fundstücken zusammengesteckte Schlafhütte für bis zu 17 Männer. Vorn links schaut Apo auf einen Zettel. Das Bild täuscht. Die Männer schauen selten etwas an in dieser hektischen Arbeitsphase; sie greifen und werfen das Gegriffene zielsicher in Richtung seines Haufens, ohne die Bewegung zu unterbrechen – Papier zu Papier, Dose zu Dosen, Plastik zu Plastik, Elektrogeräte in die eine Tonne, Röntgenbilder in eine andere … Das Bild entstand bei einem unserer Besuche im »Depot« jener Gruppe, aus der drei Männer zu Protagonisten unseres Stücks »Herr Dağaçar und die goldene Tektonik des Mülls« wurden, uraufgeführt sechs Monate später in der gleichen Stadt, dann auf Gastspiel hier und da in Europa. Das Foto entstand wie hunderte andere im Bewusstsein, dass das, was wir dort sehen, so auf der Bühne nicht gezeigt werden kann – und dass wir es vergessen würden bei der Arbeit mit den Leuten, die auf dem Foto zu sehen sind. Vergessen, weil sich die Realität der Begegnungen immer neu überschreibt, das Bild ständig verändert in dieser Dauerbelichtungskamera, die die Black Box des Theaters ist.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 14/2011, pp. 50–51.

-

Rimini Protokoll: Because the Reality of the Encounters Always Newly Overwrites

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 50–51.

Abdullah »Apo« Dağaçar, Aziz İdikurt, Bayram Renklihava, Mithat İçten, in »Herr Dağaçar und die goldene Tektonik des Mülls« von / by Helgard Haug und / and Daniel Wetzel (Rimini Protokoll; Istanbul, Berlin, Essen, Rotterdam 2010).

-

-

-

MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, RUTI SELA & MAYAAN AMIR

Ruti Sela & Mayaan Amir: Triggering the production of Ideological Positions

Q In your work you juxtapose a documentary idiom with fictitious interventions, while interpolating areas of violence, aggression, submissiveness and blind ideological obedience. It has often been written about your trilogy “Beyond Guilt” (2003–05) that it’s a work about issues of Israeli identity, about the entanglement of sex and the structural violence of the state. Sexual and political-military identities seemed to be intermingled to an extent that distinction is no longer possible. In public toilets of nightclubs, for example, you seduced female, obviously lesbian Israeli soldiers to a French kiss, then they lashed out with aggressive comments about Arabs afterwards. Your sex dates in a hotel room with men who were in the army ended up with not having sex, but conversations leading to the army and the omnipresent military conflicts. So with your films you expose the overpowering influence of the military on Israeli society even in the most private moments.

But your filmic strategy also seems to underline an understanding of your work as feminist intervention, too. The relationship between the director and what/who is being filmed is constantly thematised. You seduce your interviewees with the camera on the one hand, but then by turning the camera around on yourself, you make it relatively clear that you are the subject of action, you are conducting the whole scene. In the last film of your trilogy you asked the woman being interviewed by you—a prostitute—to take over the camera work, obviously to avoid having her end up as an object or even a victim in front of the camera, to grant her (sexual) integrity, to grant her a position as a subject of the scene by leaving it up to her to conduct it.Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 52–54.

-

Ruti Sela & Mayaan Amir: Triggering the production of Ideological Positions

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 52–54.

Ruti Sela & Mayaan Amir, Stills aus dem Video / from the video: Beyond Guilt #2, 2004.

Aus der Triologie / From the trilogy: Beyond Guilt, 2003–05.

-

-

-

MAREN LüBBKE-TIDOW, RENZO MARTENS

Renzo Martens: We Don't Actually Know What We're Seeing

[…] As I’ve tried to demonstrate in the Congo film, and as we have learned from Godard and many others, the power balances between those who produce and consume images on the one hand, and the power balances between those who consume and produce cocoa or coltan or diamonds, are virtually the same.

By disclosing the terrible discrepancy in agency within this film, I think the piece also offers a deep insight into what leads to the production of cocoa and coffee, and to poverty, exploitation, etc.—more objectively than if I had just filmed exploitation as an external phenomena.

We live in a certain visual regime, and we are all set by it, educated by it—I certainly am. And to me it’s much more important to tackle that existing regime than to create alternatives to it. I think it is more important to just tackle the existing modes head on. Of course you can make art in many different ways. The film is not only a proposition, it also shows the inconsequentiality of that position—you see what costs people pay, what the price is we all pay for the inconsequentiality of the political claims of art, you see it in that film. And we need to see that somewhere a price is being paid for our beautiful gestures, because otherwise we just feed ourselves with beautiful exceptions to reality. Then art is about offering even more of Trompe l’oeil.Q So is your film work more a comment on this image production machine, or is it about the concrete, the direct—let’s say sociopolitical situation in the countries you have visited?

A However rude it may sound, Congo or Chechnya are used as existing situations, and their depictions are existing representations. I copy them and I try to open them up by intervening. In the Congo film, there are very few images that are authentic—I am not talking about me or the neon sign or the project that I created, but of the images of the Congo. They are all things which we have seen many, many times before. They are like ready-mades. But of course it’s not the Congo that is the ready-made, but the representation of Congo. And I, in the piece, am a ready-made, too—the producer, the artistic interventionist.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 55–57.

-

Renzo Martens: We Don't Actually Know What We're Seeing

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 55–57.

Doppelseite / spread: Renzo Martens, S. / pp. 56–57.

-

-

-

TOBIAS ZIELONY, THOMAS RUFF

Thomas Ruff: Optical Prostheses

Q In reference to the external world and photography, in an interview you talk about realities of first and second order. Between these realities there are photographic devices and other imaging machines that you use to produce your artistic works. Now it could be conjectured that it is specifically these machines that objectify the relationship between the material world and photography. Yet the opposite is the case. The multitude of different technical images in your work—like the shots with night vision devices, telescopes or also digital images, for example—create a kind of grey area between reference and representation. It seems to me that the concepts of visibility and visualisation are significant in this context. How do you concretely develop a new work? Do you start with “first order reality” and then look for possibilities for visualising it technically? Or is it the machines and their image-producing procedures that are at the start? In your work, you move freely between analogue and digital techniques. Can these even be separated from one another and, if so, what does the existence of digital images mean for the tense relationship between visibility and reality?

A Reality of the first order is the reality of our immediate surroundings; we perceive it with all our senses at every moment. Reality of the second order is the replica. There is only one sense involved here, the eyes. But that’s not quite true either, because we perceive with the brain, so we also use the other senses through flashbacks.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 58–59.

-

Thomas Ruff: Optical Prostheses

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 58–59.

Thomas Ruff, jpeg rl02, 2007.

C-print mit / with Diasec, 269,2 cm × 184,8 cm. Courtesy: Johnen Galerie, Berlin.

-

-

-

TOBIAS ZIELONY, TIMM RAUTERT

Timm Rautert: Participative Interest

My manner of working has changed in the sense that I reflect more strongly again on the concept of the documentary. In the sense that a documentary function is ascribed to photography, but also in the sense of its fictional character. The question of the significance of photographic images is linked with the question of their reality content.

Of course this becomes obsolete with the decline of analogue photography and the traditional terminology of the photographic. An algorithmically generated image does not necessary hold a reference to reality. We need a different name for these new images, perhaps we should no longer call them photography.

A young photographer today faces the same questions as they did then: What should I do, what can I do, what do I want to know? They have to invent themselves, as they had to do in the past. Admittedly, in an increasingly difficult, more complex world today.Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 60–61.

-

Timm Rautert: Participative Interest

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 60–61.

Timm Rautert, Crazy Horse II, 2010. Video, loop, 27 min; Silbergelatine-print (gerahmt / framed), 40 cm × 30 cm; C-print (gerahmt / framed), 40 cm × 60 cm.

Installation: galerieKleindienst, Leipzig.

-

-

-

KIRSTY BELL, COLLIER SCHORR

Collier Schorr: The Regularity of Difference

Q This photograph (“Germans and Turks”, 2006) seems particularly appropriate now, given Angela Merkel’s declaration of the failure of what she termed the “multicultural experiment”.

A It’s shocking to read about Merkel’s declaration. In some ways Germany, by virtue of the forbidden nature of Nationalism, should have been more penetrable by other cultures, but clearly it’s not really the case. When I saw the window, it seemed a perfect frame to discuss the separation of cultures. The idea of the Turkish fruit being a delicacy and more expensive was partially a motivation, as was the idea that each window opens onto a different world. But I think most clearly it is a hopeful picture about the regularity of difference.

Q The “documentary” seems an inadequate label, particularly for your ongoing series of work made in the German town of Schwäbisch Gmünd, given the often fictionalising or allegorical aspects of that work …

A When I speak of documentary, I am also speaking about the predicament of working in a medium that is scrutinized for its veracity. If an artist who uses photography is interested in anything “past”, the work is seen as theatrical or fictionalised. I have always allowed myself to make portraits from another time, but because I am outside I see them as documentation—I am looking at the subject from a distance, though not necessarily objectively.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 62–63.

-

Collier Schorr: The Regularity of Difference

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 62–63.

Collier Schorr, Germans and Turks, 2006. Pigment-print, 78,7 cm × 98,1 cm.

Courtesy: 303 Gallery, New York.

-

-

-

TOBIAS ZIELONY, UCHIHARA YASUHIKO

Uchihara Yasuhiko: The Untaken Photos

A While shooting, sometimes I feel concerned about the images that I wasn’t able to capture. In many cases, I have a feeling that I am not able to take photographs the way I want to.

Photographs that I wasn’t able to take or photographs that I didn’t take—these can only be imagined and do not have a real existence. However, in my dreams or during random moments, I think about these images that I didn’t capture. Sometimes I can’t tell the difference between whether these exist solely in my imagination or whether I am remembering the photographs that I actually took.

Perhaps the photographs that I take are the residue of the photographs that I wasn’t able to take. I do think that my photographs are supported by the ones that I wasn’t able to take.

Japanese culture places a value on works of art that are imperfect or incomplete. In ceramics for example, just before the potter reaches a perfect shape, the wheel is stopped and the work is left with a slight skew. Beauty is even found with the cracks and chips in the glaze and clay. In architecture, one of the pillars is placed upside down or one part of the building is always left incomplete. With ink paintings, much of the surface is left blank, showing the white of the paper. In my work, I seek inspiration from such values. According to this way of thinking, the two opposite poles of being “complete” and “incomplete” do not exist, and instead what is born is a much deeper and careful manner when viewing each work of art.Text feature in Camera Austria International 14/2011, pp. 64–66.

-

Uchihara Yasuhiko: The Untaken Photos

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 64–66.

Uchihara Yasuhiko, DSC, 2007.

-

-

-

SABINE SPILLES, LARRY FINK

Larry Fink: The Notion of Empathy

Q What, in your opinion, is documentary photography? Do you consider yourself a documentary photographer?

A Well, it’s interesting, I mean you start off with photography, and photography in the old style, how it was utilised, was the looking at something as to document it. The camera in its origins had a startling veracity—but still, it just plucks the real out of the air and puts it on to an engraving. Any document, which is taken by a camera, is always going to be subject to the whim of the photographer, may it be by choice or by chance.

Q So the documentary, just like objectivity, would be something like an ideal one might be chasing, although it is impossible to reach it.

A Right, the theory of the document is an ideal state of non-motion.

One thing is given into a machine to make its exact replication and then it turns out to be the same as it was when it started—in a photograph it can’t be that way. It lives! Everything in photography, since it’s an instantaneous moment, which is basically opening its yowling mouth for experience, is going to be influenced by the nature of the hunger of that mouth and where it tends to want to eat— yum yum!Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 67–68.

-

Larry Fink: The Notion of Empathy

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, S. / pp. 67–68.

Larry Fink, Hazel Dickens (1935–2011), Washington D.C., 12/2002. Aus / From: Somewhere There’s Music, Bologna: Damiani, 2006, S. 96.

-

-

WALID SADEK

A Time to See 2/4 The Present of Seeing Eyes

A painting by the French artist Léon Cogniet (1794–1880) titled “Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter” (ca. 1843) depicts the Venetian master-painter sitting in a darkened room lugubriously relieved by crimson light. To his right stands an easel with a stretched canvas faintly marked with the outlines of a sleeping face. To his left lies supine his daughter Marietta.

Cogniet’s painting is an example of an academic genre quite popular among salon audiences between the 1820’s and the end of the 19th century. A genre renowned for staging and dramatising chapters from the biographies of Old Masters: paintings inhabited by painters.1 Cogniet’s canvas clearly belongs to this genre. It stages the death of Tintoretto’s daughter Marietta. The painting is formally academic. The lighting is contrived and the face of the dead daughter is an obvious reference to Bernini’s ecstatic Saint Theresa. And yet it is surprisingly evocative of a temporality that is of the eyes proper: the father painter looks to his left as if absorbed by what is still present, while his right hand holding the brush rests on his thigh just above the right knee, having abandoned the incipient face on the canvas for a moment that lingers. Apparently placed in between drawing and object, Tintoretto sits rather in the gulf born of a seeing severed from drawing.Text feature in Camera Austria International 114/2011, pp. 69–70.

Exhibitions

Aernout Mik: Communitas

Jeu de Paume, Paris

Museum Folkwang, Essen

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

CHRISTA BLÜMLINGER

The Otolith Group: Thoughtform

MACBA, Barcelona

Ibon Aranberri: Organigramma

Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona

1979, a Monument to Radical Moments

La Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona

ALBERTO MARTÍN

Stefan Panhans: Wann kommt eigentlich der Mond raus?

Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen.

JULIA GWENDOLYN SCHNEIDER

Paul Graham: Photographs 1981–2006

MARTIN HERBERT

A Hard, Merciless Light: The Worker-Photography Movement, 1926–1939

Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid

RUDOLF STUMBERGER

Staging Action: Performance in Photography since 1960

MoMA, New York

RACHEL BAUM

FotoSkulptur. Die Fotografie der Skulptur bis heute

MoMA, New York,

Kunsthaus Zürich

THILO KOENIG

Dislocación. Kulturelle Verortung in Zeiten der Globalisierung

Kunstmuseum Bern

SØNKE GAU

unExhibit

Generali Foundation, Wien

CHRISTIAN HÖLLER

Yto Barrada: Riffs

Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin

REINHILD FELDHAUS

Miki Kratsman: all about us

Ursula Blickle Stiftung, Kraichtal

GISLIND NABAKOWSKI

Manfred Willmann: Arbeit

SANDRA KRIŽIĆ ROBAN

Inés Lombardi: Past Present – Close and Distant

MANISHA JOTHADY

Nadim Vardag

TANJA GASSLER

Martin Bilinovac: Exposure

DANIELA BILLNER

Books

Das Verschwinden der Revolution in der Renovierung.

Die Geschichte der Gropius-Siedlung Dessau-Törten

Gebrüder Mann Verlag, Berlin 2011

JOCHEN BECKER

Joanna Rajkowska, Sebastian Cichocki: Dogs from Üsküdar

Fundacja Sztuk Wizualnych / Foundation for Visual Arts, Krakow 2011

KRZYSTOF PIJARSKI

Joanna Rajkowska, Sebastian Cichocki: Dogs from Üsküdar

Fundacja Sztuk Wizualnych / Foundation for Visual Arts, Krakow 2011

SEBASTIAN CICHOCKI

The Studio Reader: On the Space of Artists

KIRSTY BELL

Sandra Krizic-Roban: At Second Glance.

Positions of Contemporary Croation Photography

Institute of Art History and UI-2M plus, Zagreb 2010

WALTER SEIDL

Imprint

Publisher: Reinhard Braun

Owner: Verein CAMERA AUSTRIA. Labor für Fotografie und Theorie. Lendkai 1, 8020 Graz, Österreich

Editor-in-chief: Maren Lübbke-Tidow (V.i.S.d.P.)

Editors: Margit Neuhold, Sabine Spilles

English proofreading: Dawn Michelle d´Atri, Aileen Derieg

Translators: Dawn Michelle d´Atri, Aileen Derieg, Andy Jelcic, Caroline Elder, Wilfried Prantner, Josephine Watson

Dank / Acknowledgements:

Jens Asthoff, Kirsty Bell, Ariane Beyn, Laurence Bonvin, Annett Busch, Peggy Buth, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Laurie Cluitmans, TJ Demos, Justine Durrett, Larry Fink, Anna-Catherina Gebbers, Paul Graham, Simon Greenberg, David Goldblatt, Hans-Jürgen Hafner, Susanne Holschbach, Bertram Keller, Kai Kolblitz, Alexander Kluge, Sharon Lockhart, Frederico Martelli, Renzo Martens, Timm Rautert, Jo Ractliffe, Jorge Ribalta, Rimini Protokoll, Thomas Ruff, Michael Schmidt, Collier Schorr, Hanna Schouwink, Walid Sadek, Ruti Sela & Mayaan Amir, Melanie Ohnemus, Marie Röbl, Alexandra Schott, Ahlam Shibli, Hito Steyerl, Nadja Talmi, Ben Thornborough, Wolfgang Tillmans, Helmut Weber, Jan Wenzel, Beata Wiggen, Peter Yardley, Uchihara Yasuhiko, Kai Yoshiaki, Tobias Zielony

Copyright © 2011

Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Nachdruck nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung des Verlags. / All rights reserved. No parts of this magazine may be reproduced without publisher’s permission.

Für übermittelte Manuskripte und Originalvorlagen wird keine Haftung übernommen. / Camera Austria International does not assume any responsibility for submitted texts and original materials.

ISBN 978-3-900508-88-3

ISSN 1015 1915

GTIN 4 19 23106 1600 5 00114