Camera Austria International

156 | 2021

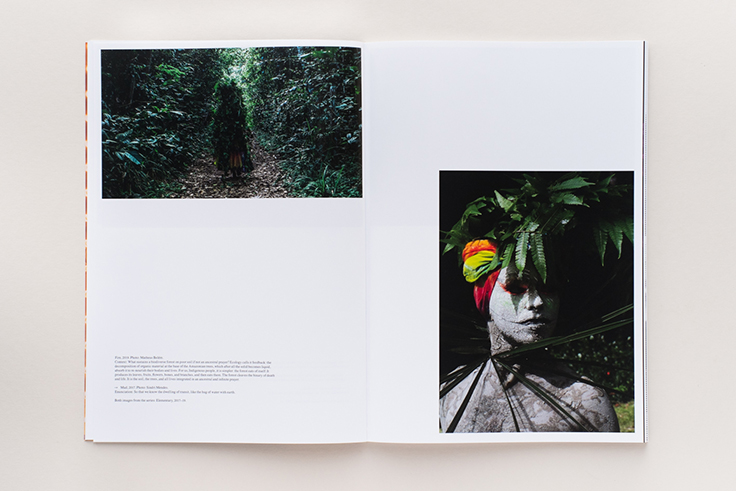

- UYRA SODOMA

Re-enchanting Life - LEANNE BETASAMOSAKE SIMPSON

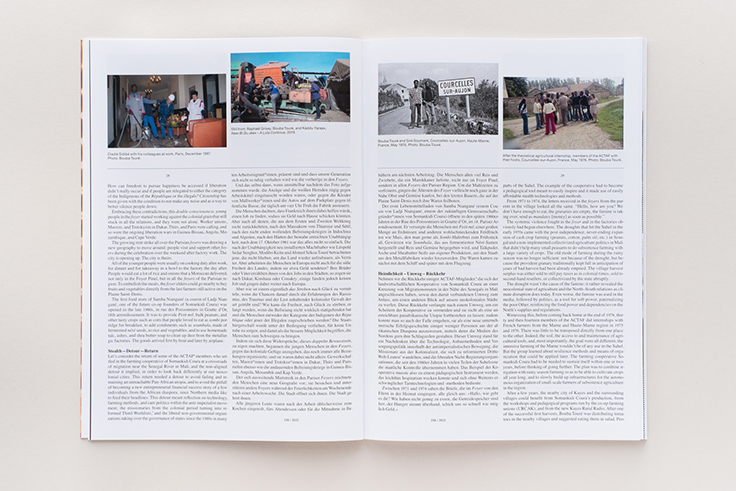

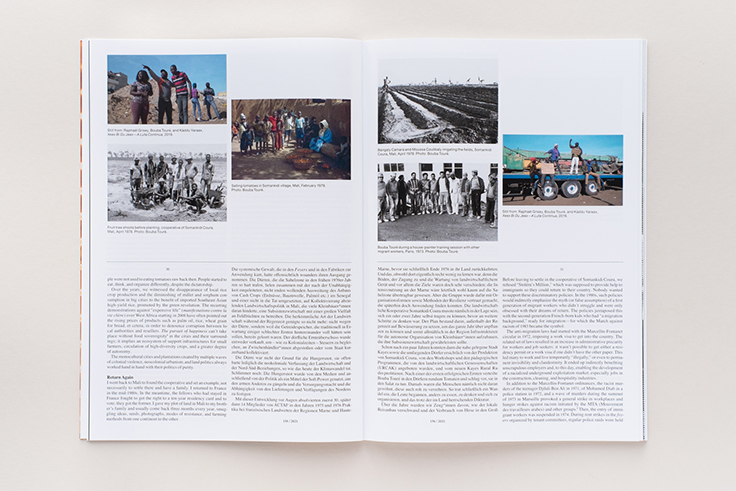

Mino-Bimaadiziwin: The Good Life - RAPHAËL GRISEY / BOUBA TOURÉ

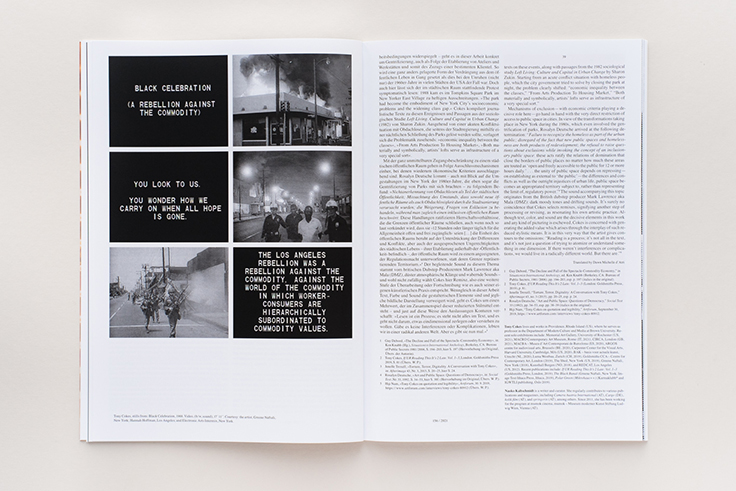

Happiness Against the Grain - TONY COKES / NAOKO KALTSCHMIDT

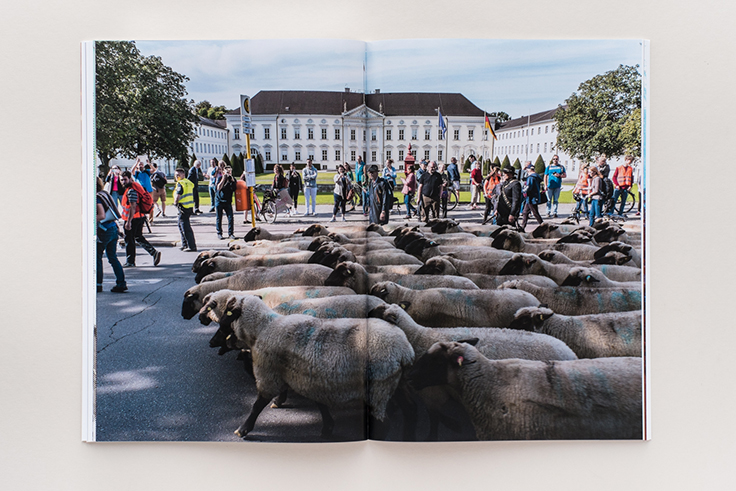

Urban Protests and Negative Spaces: Displacement from Public Life - JÖRG HEISER

No Good Life without Remembrance - NICOLE SIX & PAUL PETRITSCH

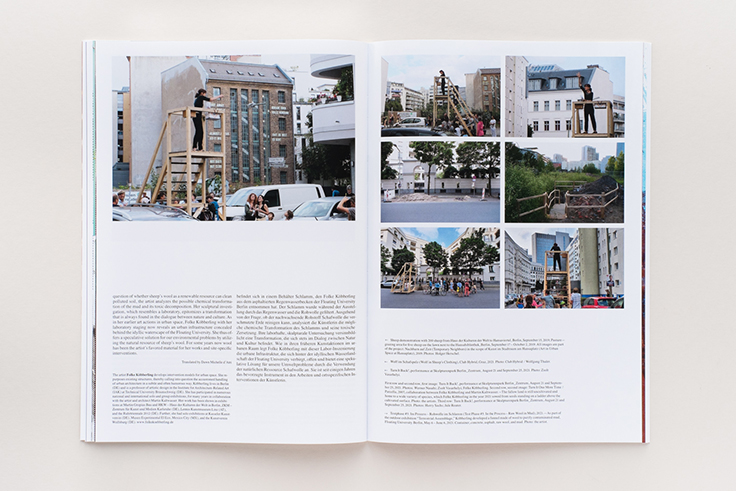

Echo Space: A Sphere of Activity and Agency - FOLKE KÖBBERLING

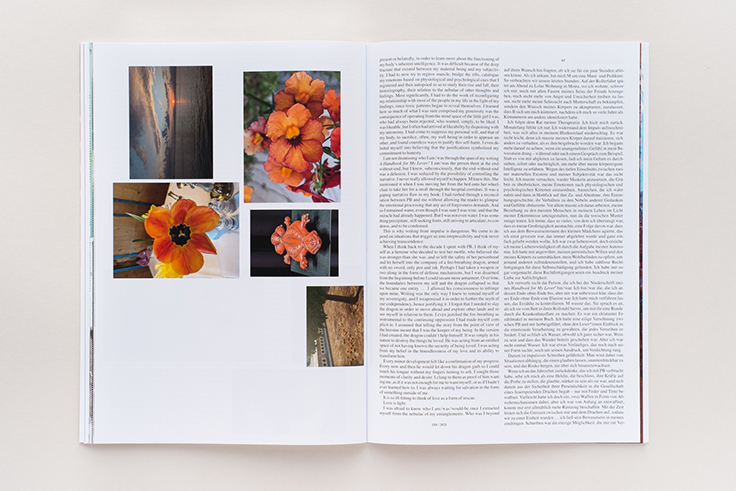

Temporary Neighbors - ROSALYN D'MELLO

Die Metamorphose

- SABRINA ASCHE

About People in One Place

Preface

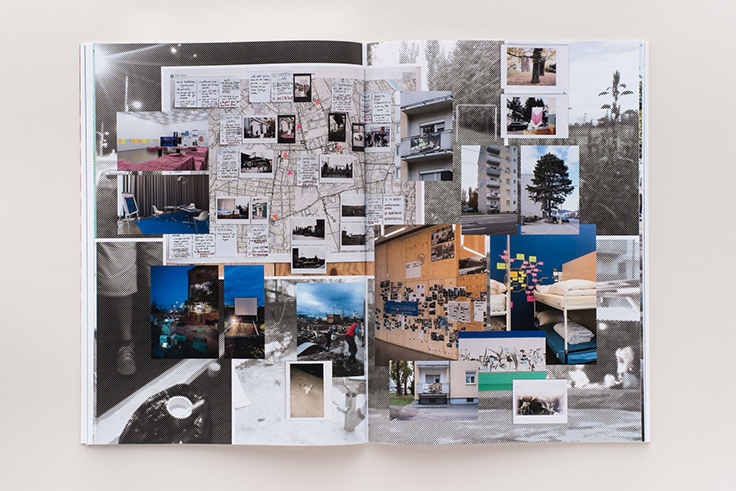

In a time of environmental degradation, wasted resources, and political inaction, thinking about a “good life” seems nearly impossible. Camera Austria nevertheless responded to the call for tenders by the City of Graz within the framework of Graz Kulturjahr 2020 with the project The City & The Good Life, which was conceived by the entire board of the association and developed in close collaboration with Daniela Brasil. It was finally able to begin in September 2020 and came to an end in May 2021 with the exhibition curated by Urban Subjects If Time Is Still Alive. This project—among many other, in part surprising experiences—clearly showed how very localized urbanities are constructed and composed, are fragmentary and at times fleeting, and that many of them exist in parallel without necessarily perceiving or knowing very much about each other. The urban here and now is difficult to demarcate, since social media, streaming services, and online shops connect us with all kinds of cultural, aesthetic, and political ideas. People talk about a possible city in common in different languages, and such a city is designed with a wide range of concepts. These different designs, requirements, aspirations, and disappointments resonated in the Echoraum (Echo Space) by Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch. . . .

This issue of our magazine attempts neither to document the loss of the idea of a city in common or a good life, nor reconcile us with this loss. Within the framework of the project The City & The Good Life, we tried to initiate processes that would at least provide ideas about possibilities for reclaiming and re-appropriating them again in another form. In the invitation to the artists and authors in this issue, we thus correspondingly wrote: “What resources, networks, and opportunities to partake of a good life in the city have been neglected as a result of the predominantly economically oriented hierarchies of the neoliberal city? . . . Against what regulations and governing techniques will this idea of a good life have to be demanded more intensively in the future?”

Entries

Exhibitions

Biennale für Freiburg: BfF #1

Verschiedene Orte, Freiburg im Breisgau, 10. 9. – 3. 10. 2021

WALTER SEIDL

The Politics of a Liminal Place

steirischer herbst – The Way Out

Various venues, Graz and environs, 9. 9. – 10. 10. 2021

LARA SCHOORL

Art Club2000: Ausgewählte Werke 1992 – 1999

Kunsthalle Zürich, 18. 9. 2021 – 16. 1. 2022

Artist Space, New York, 22. 10. 2020 – 30. 1. 2021

SØNKE GAU

Female Sensibility: Feministische Avantgarde aus der SAMMLUNG VERBUND

Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz, 24. 9. 2021 – 9. 1. 2022

VANESSA JOAN MÜLLER

Massao Mascaro: Sub Sole

Fondation A Stichting, Brussels, 25. 9. – 19. 12. 2021

STEVEN HUMBLET

Shiraz Bayjoo: La Sa La Ter Ruz

Fondation H, Paris, 16. 9. – 20. 11. 2021

MICHÈLE COHEN HADRIA

Cristina Lucas: Maschine im Stillstand

Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, 15. 8. – 31. 10. 2021

MITCH SPEED

Felix Dreesen: Von Wolkenschäden

GAK – Gesellschaft für aktuelle Kunst, Bremen, 28. 8. – 24. 10. 2021

RAINER UNRUH

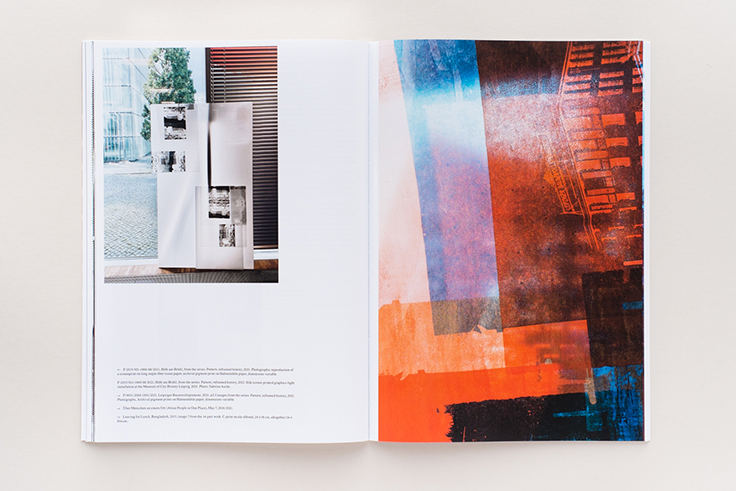

Aglaia Konrad: Japan Works and Other Books

Enter Enter – A Space for Books, Amsterdam, 11. 9. – 10. 10. 2021

REINHARD BRAUN

L’image et son double

Galeries de photographie – Centre Pompidou, Paris, 15. 9. – 13. 12. 2021

NINA STRAND

Primrose: Early Colour Photography in Russia, 1860s–1970s

MAMM – Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow, 2. 9. – 5. 12. 2021

AGNIESZKA GRATZA

Margot Pilz: Selbstauslöserin

Kunsthalle Krems, 23. 10. 2021 – 3. 4. 2022

CHRISTINA NATLACEN

Pauline Curnier Jardin: WAITING FOR AGATHA, SEBASTIAN AND THE REST OF THE HOLY CHILDREN—UNFOLDING A FILMIC RESEARCH

Index – The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation, Stockholm, 2. 9. – 13. 12. 2021

ASHIK and KOSHIK ZAMAN

Moderne Zeiten: Industrie im Blick von Malerei und Fotografie

Bucerius Kunst Forum, Hamburg, 26. 6. – 26. 9. 2021

PAUL MELLENTHIN

… oder kann das weg? Fallstudien zur Nachwende

nGbK – neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin, 16. 9. – 17. 11. 2021

JANA NORITSCH

Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic* & Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński

Kunsthalle Wien, 22. 10. 2021 – 6. 2. 2022

BETTINA LANDL

Books

Talking Books

Erik van der Weijde in Conversation with . . . Mike Slack

Mike Slack: OK OK OK

J&L Books, Atlanta / New York 2002

Mike Slack: THE TRANSVERSE PATH (Or Nature’s Little Secret)

The Ice Plant, Los Angeles 2017

Elisabeth Neudörfl, Out in the Streets

Hatje Cantz, Berlin 2021

CAROLIN FÖRSTER

Katja Stuke & Oliver Sieber, Paris, 8. Dec 2018. La Ville Lumière

Boehm Kobayashi, Köln; Éditions GwinZegal, Guingamp 2021

SABINE MARIA SCHMIDT

DISCOURSE

MACK, London, 2020–ongoing

MARINUS REUTER

Imprint

Publisher: Reinhard Braun

Owner: Verein CAMERA AUSTRIA. Labor für Fotografie und Theorie.

Lendkai 1, 8020 Graz, Österreich

Editor-in-Chief: Christina Töpfer.

Editor: Margit Neuhold.

Translations: Dawn Michelle d’Atri, Nicholas Huckle, Amy Klement, Peter Kunitzky, Wilfried Prantner, Alexandra Titze-Grabec.

English Proofreading: Dawn Michelle d’Atri.

Acknowledgments: Sabrina Asche, Daniela Brasil, Tony Cokes, Jörg Dittmer, Florian Ebner, Raphaël Grisey & Bouba Touré, Jörg Heiser, Sarah Maria Kaiser, Naoko Kaltschmidt, Jelena Kalu-djerović, Peter Kunitzky, Folke Köbberling, Andrej Krementschouk, Marissa Lobo, Ivana Marjanović, Rosalyn D’Mello, Christina Natlacen, Ulrike Otto, Heidi Pretterhofer, Michael Rieper, Philip Schütz, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Franziska Schmidt, Eduardo Sotomayor, Katja Stuke & Oliver Sieber, Urban Subjects (Sabine Bitter, Jeff Derksen, Helmut Weber), Uýra Sodoma.

Copyright © 2021

No parts of this magazine may be reproduced without publisher’s permission.

Camera Austria International does not assume any responsibility for submitted texts and original materials.