Press information

The Militant Image

Picturing What Is Already Going On, Or The Poetics of the Militant Image

Infos

With

Raymond Boisjoly (CA)

Harun Farocki (DE)

Peter Friedl (AT)

Sharon Hayes (US)

Marine Hugonnier (BE)

Alfredo Jaar (US)

Emily Jacir (PS)

Walid Sadek (LB)

Jayce Salloum (CA)

Ines Schaber (DE)

Paola Yacoub (LB)

Opening

27.09.2014, 1 pm

Duration

28.9.–16.11.2014

Pre-opening artist’s talks

Mit Jayce Salloum (CA), Paola Yacoub (LB), Urban Subjects (AT/CA)

25.9.2014, 5 pm

Militant Image – Workshop as part of steirischer herbst

9. & 10. 10. 2014

A project by

Urban Subjects (Sabine Bitter, Jeff Derksen, Helmut Weber) in collaboration with Camera Austria

Co-produced by

steirischer herbst 2014

»I prefer not to … share!«

Press downloads

Press Information

Images of the eruption of revolutions, the momentum of particular liberation struggles, the concatenation of social movements as well as heroic or overlooked individual moments of resistance and refusal—and even acts of courage and love—have historically built an archive of militant images. Yet, as powerful as images of militancy remain—from militant cinema to movement posters to images grabbed in the heat of the moment—their impact within a contemporary media landscape saturated with images of social unrest is not guaranteed. In the political and media terrain of the present, what makes an image militant?

The militant image of any period is in dialogue with its historical present at the same time as it contests the shape of the present. Kodwo Eshun and Ros Gray convincingly argue that bringing past moments of struggle, as they are pictured in the militant image, into the present can ignite “a revision of the historiographies of the present” by making an “afterlife” for the militant image through recirculation.1 This complex temporality of the militant image opens the past through historical, affective, and profoundly political conjunctures. Sparking off of the conditions of our present as “a thing that is sensed and under constant revision,”2 the militant image gives a political and affective weight to the imagination of future acts of militancy. Yet, despite a productive and poetic hope in the ability of the militant image to both represent and produce acts of militancy—to be the image of a condition and to create that condition—the militant image is not self-identical to militancy but agitates the expectation of representation and builds a visual politics.

As an aesthetic form, the militant image is made militant through its relation to its historical occasion and through circulation within an affective counter-economy; within this economy, the militant image aligns with existing potentials and affects within and through communities, moments, and sites. As an intensity within an affective economy, militancy does not reside solely in the image, “but is produced only as an effect of its circulation”, to paraphrase Sara Ahmed.3 The militant image therefore cannot be simply singular or iconic, but it must be, as Bakhtin said of the word, half someone else’s.

This exhibition project speculates on how, in these insurgent times, images become militant by addressing the present as “a process of emergence” similar to Lauren Berlant’s reuse of Raymond Williams.4 The militant image then is tied into, and productive of, structures of feeling that cohere through time contesting the dominant, recirculating the residual, and joining the energy of the emergent. Spaces of struggle—such as national liberation, regional autonomy, or place-based struggles—are not necessarily more residual or indistinct today, but they are—in this period of surveillance, migrancy, and biopolitical and state power—differently constituted. How, in this oscillation of the temporalities of the present, can a militant image cohere with what the geographer Neil Smith calls “the revolutionary imperative” that he identifies as a compelling historical force?5 Can we assume a new aesthetic regime of visibility for militancy or does militancy only become visible when it is in the making?

The militant image is necessarily inside the very social conditions that it is shaped by and reacting against. Specific forms of power generate particular forms of militancy and the militant image reflects the plurality of power: the militant image is a part of what is already going on. The exhibition “The Militant Image: Picturing What Is Already Going On, Or The Poetics of the Militant Image” recognises a multitude of militancies, each of which calls for a particular aesthetic approach. So as not to lapse into mere pluralities, our curatorial aim is based on productive antagonisms which bring forward various types of militancies and modes of militant representation. These forms of militancy overlap temporally, spatially, and politically. The militant image is half the past’s and half

the future’s even as it is grounded in the historical occasion of the present.

1 Kodwo Eshun and Ros Gray, “The Militant Image: A Cine-Geography: Editors’ Introduction”, Third Text 25 (2011), p. 2, 3, 11.

2 Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), p. 4.

3 Sarah Ahmed, “Affective Economies”, Social Text 79 (2004), p. 3.

4 Lauren Berlant, op cit., p. 7.

5 Neil Smith, “The Revolutionary Imperative”, Antipode 41 (2010), pp. 50–65.

Raymond Boisjoly

Boisjoly’s work troubles the representation of Indigenous or First Nations people by running it through mediations that are both technical and cultural. For this exhibition, Boisjoly has produced a text-image work with the phrase, “Where we were is no longer where we are and where we will be is not yet”, that agitates an understanding of both the present and the temporality of agency and Indigeneity. This seemingly direct statement alters an understanding of the temporality of the present as a neoliberal now, the now of the end of history. But within a frame of the colonial present forced upon First Nations people, this sentence takes on the militancy of critique and of an utterance that requires a response. The alternative temporality invoked is also informed by Indigenous literary constructs that signal the presence of the past and tradition. Of the politics of language and representation in his work, Boisjoly has said: “I am interested in the way something like ‘colonialism’ can never be regarded directly, but only glimpsed in the specific mechanisms that come to impact colonised populations.”

Harun Farocki

This 1969 film, “Nicht löschbares Feuer” (“Inextinguishable Fire”), by Harun Farocki catches the problematic of the militant image; how can an image, any image, possibly represent the technology and devastation of war as they were emerging from Vietnam? Farocki’s film addresses this problematic of the counter economies of affect and carefully avoids shock as the affective attunement. Instead, “Nicht löschbares Feuer” sets out to make a case through facts, staged scenes, and subtle agit-prop against the nexus of science, war, and capital. The militancy of Farocki’s film is both in its aesthetics and in its intent—to fight the use of napalm before it becomes an inextinguishable fire, it must be stopped at the point of production: “When napalm is burning, it is too late to extinguish it. You have to fight napalm where it is produced: in the factories.”

°“Nicht löschbares Feuer” holds in balance a moment when protest, refusal, and militancy shortened a brutal war, but it insists on the relationship of the historical occasion, specific action, and the militant image.

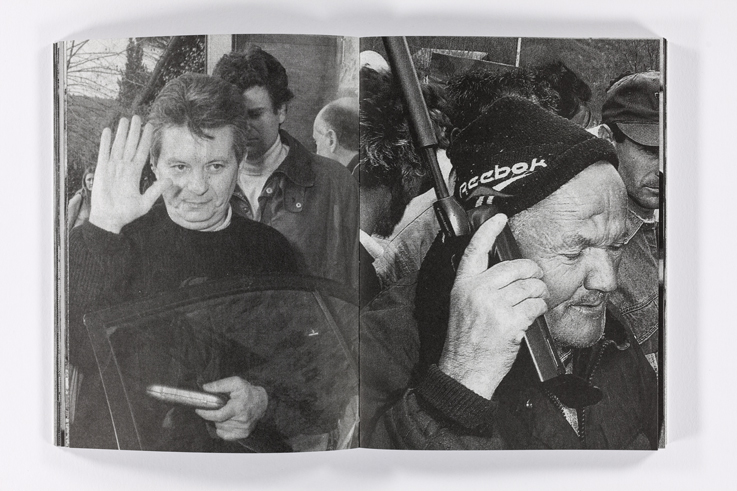

Peter Friedl

Peter Friedl amassed what he calls a “lyrical” collection of newspaper photographs of protest images from across the geopolitical spectrum from 1992 to 2010. A selection of these images, which Friedl also characterises as images of “public integrity and intimacy”, were ordered according to their historical chronology rather than their publication in the global infoscape when they were first published by MACBA as a bookwork in 2006. This recirculation of newspaper images disrupts the media framing known as “the protest paradigm” which portrays protest as a spectacle of confrontation and buries the actual causes of the protest. The project’s title “Theory of Justice” also refers to the American philosopher John Rawls’s examination of the role of justice within a °“well-regulated society” in A Theory of Justice.1 Rawls’s take on the social contract based on a distribution of rights and responsibilities has been battered by neoliberalism’s splitting of rights and responsibilities and its rending of the social contract to individuated success and failure. But, Friedl’s modified title, with the singularity implied by A Theory of Justice dropped, turns back to a larger questioning of justice and its pictorial representation today. Friedl’s assertion “it’s a project on pictorial justice” joins representation, aesthetics, and justice.

1 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971).

Sharon Hayes

In an important moment in queer political activism, Anita Bryant—singer and spokesperson for both Florida orange juice and for the homophobic Save Our Children campaign—had a fruit pie thrown in her face by Thom Higgins in 1977. The pie toss was a militant act against Byrant’s public program against what she called “militant homosexuality.” And as a performative act of mass mediation, and intervention into a press conference for Byrant’s crusade to overturn a gay anti-discrimination bill in Dade County, Florida, that pie in the face was immediately and historically a militant image. As part of Sharon Hayes’s practice of the recirculation of historical moments into new affective circuits and into new political possibilities, “I Saved Her a Bullet” (2012), brings this militant image into the present via a residual technology—the overhead projector. Hayes’s projection points toward the necessity of future actions through a“temporal opening.” For as crude as Bryant’s campaign appears today, the same roll-back of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, and Queer (LGBTQ) rights continues. It is this militant temporality of art and politics that animates much of Hayes’s work as it aims at the production of what Simon Critchley calls “future social actors.”1

1 Simon Critchley, Infinitely Demanding: Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance (London: Verso, 2007).

Marine Hugonnier

Marine Hugonnier’s essay-film “ARIANA” (2003), begins with the quest to film a panoramic view of Panjsher Valley in Northern Afghanistan, a valley that has largely escaped military interventions by the Soviets and the Taliban due to the Hindu Kush mountain range. However, due to a landslide, Hugonnier is unable to film the valley and as she turns back to Kabul, the film shifts to a self-reflexive criticality and questions its own desire to grasp the valley through the colonial tropes of vision and possession as well as a militaristic scopic regime. After this initial disruption of the certainty of documentary representation, the film questions the very gaze that it is constructing. Hugonnier’s voiceover links the film to critiques of film’s ability to seamlessly join space into a unified whole and thus obscuring space as a social process. The militancy of this refusal to represent the Panjsher Valley or Kabul foregrounds both the role of filmic devices and scopic regimes as aspects of the militant image.

Alfredo Jaar

In the bookwork A Hundred Times Nguyen (1994) Alfredo Jaar repeats four portraits of a young girl he photographed in a refugee camp in Hong Kong in 1991. Jaar deploys a combinatorial method of these four images to represent a subject who has been cut loose or abandoned by modernist social promises. Through this repetition and iteration, Jaar stages a contradiction born at the heart of revanchist globalisation and neoliberalism—that the production of surplus populations demands a political and ethical response. Jaar counters the structural dismissal of the surplus human subject by vagabond capitalism and the erosion of networks of social reproduction with a powerfully humanist gesture shaped by machinic repetition—a portrait repeated and then circulated in an affective economy that both particularises and universalises the condition of the refugees. This dialectical tension is not resolved in Jaar’s migrant image (to use a term from T. J. Demos1) as Jaar both leans on and breaks down representational narratives to build an image against the abandonment of a single person: as in much of Jaar’s work, there is a militancy in the ethical force of the image. With the poster, “You Do Not Take a Photograph. You Make It.” (2013), Jaar’s statement insists on the active and performative aspect of a photograph where its production of meaning and affect is mutual and potentially militant.

1 T. J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

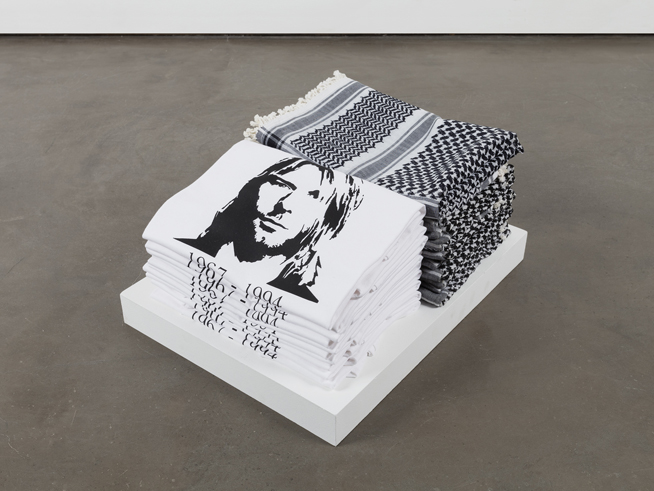

Emily Jacir

Emily Jacir’s work “Bethlehem street corner”(1998) is a diptych of two differently coded aspects of globalized culture: a stack of sharply folded t-shirts with a posterised black and white image of Kurt Cobain with the dates of his birth and dramatic death (1967–94) edged up against an equal stack of black and white keffiyehs, now a global political sign of solidarity with Palestine. Coinciding with Kurt Cobain’s death in 1994, the Palestinian Authority was established in Gaza and the West Bank. Jacir who had been photographing the city of Bethlehem throughout the first Intifada witnessed first-hand from her hometown in Bethlehem the signing of the Oslo Accords and the arrival of the PA, when t-shirts with Kurt Cobain face were in all the marketplaces and on the streets. Her diptych was inspired from the local production of t-shirts with pop culture figures juxtaposed with the local production of keffiyehs. Despite rock and roll and real politics being an uneasy fit, this work draws parallels between the circulation of affective politics through cultural rebellion and solidarity with anti-colonial movements. The other work in the show materialises a different form of militancy: Jacir’s future Israeli stamps, commissioned by Cabinet magazine for its Books of Stamps, 2007, revisits the mail art movement. Specifically, Jacir produced stamps for the future state of Israel based on US stamps that use images of so-called “American Indians”. By foregrounding the relationship between power, negation, and commemoration, and pointing to occupation and colonialism today, Jacir has switched images from Palestinian culture and history with the corresponding images of the Indigenous people pictured on the US stamps to make stamps for “the future state of Israel”.

Walid Sadek

Sadek’s work consistently frames questions about the possibilities and difficulties of visual representation and the role of art within the context of “the protracted war” in Lebanon. Continuing his exploration of the possibilities of text and installation, as well as the act of reading, Walid Sadek has produced a new architecturally specific text work for the Camera Austria gallery space from a new series entitled, “Thoughts on Preparedness” (2014). He writes, “The sentence [‘That the image is an encounter and as such is unpredictable’] is one of fourteen propositions on the Image; the Image as a disruptive apparition.” This invocation of the image as a disruptive apparition and as a moment of meaning that evades paraphrase or easy containment is tellingly proposed in text, a system which is sign-based and equally open to the dialogic encounter. Here the problematic and possibility of the militant image are staged through the event of language where its politics lie in its excesses and unpredictability rather than the monologic imperative of the closed text.

Jayce Salloum

For this exhibition Jayce Salloum will construct a new photographic constellation, “location/dis-location(s): gleaning spaces” (2014), from his long-running work, “untitled: photographs”, a fluid archive of images that negotiate spatial, cultural, racial, and economic mediations. These photographic constellations are remarkable in their creation of semantic clusters, imagistic and political juxtapositions, as well as the textures and density that they build up. Both rigorously arranged yet structurally open, these constellations enact a critical position of the viewer, who is drawn into the multiple focal points of the work. Yet, the intricate works are also based upon a previous instance of critical reflection in which Salloum takes the photograph, for each photograph itself holds meaning in tension through Salloum’s framing of the everyday with moments of flux and transition. Salloum’s works are a critical reflection on set knowledges of the nation-state, identity, and geopolitics at the same time as they are assertions of the material effects of the violence of capital, imperialism, and our present mode of colonialism. The subtlety of Salloum’s work allows it to be resolutely place-based and to reconfigure place beyond its immediate scales.

Ines Schaber

Ines Schaber’s “Culture Is Our Business” (2004), traces an image of miltancy on a street in Berlin’s press district in 1919 as it moves into photo agencies, the photographer’s archives, and into the Agency for Images of Contemporary History, a project by Schaber and a group of friends. Ironically, copies of Willy Römer’s photograph of revolutionaries crouched behind a barricade, rifles sticking through what appears to be stacks of newspapers, are also held in the archives of Corbis, the stock agency founded by Bill Gates. This image of revolutionary militancy not only loses its historical specificity in the Corbis archive (as it is misidentified), but as a digitised commodity, its circulation within affective economies where it can join other counter-narratives of the present is also limited. Along with the continued circulation of Römer’s photograph, Schaber’s intervention into this realm of public counter-memories, and Corbis’s containment and commodification of such images, is a letter that she wrote to Bill Gates which is laid over part of Römer’s image in “Culture Is Our Business”. In this construction, as with her other works, Schaber draws together the politics of visibility, of access, and of representation.

Paola Yacoub

In the summer of 1988, at an intense moment in the Lebanese civil war, as Yacoub assisted a photojournalist documenting aspects of the fighting and military tactics in Beirut, she took black-and-white photographs that turned away from representing specific events of the war and instead turned the camera toward the devastated urban space of Beirut. The film lab assumed that these photographs were of no use as they did not represent any tragic event, so the images were improperly developed and washed quickly which has resulted in them being yellowed today. Yet, these photographs insert an affective resonance into documentarity by breaking the expected paradigms of war photography and by foregrounding Yacoub’s particular view of the bombed urban space. Here the militant image resides obliquely in relation to the urban landscape, the historical event, and the photographic aesthetic. Even though there is an absence of what might be expected from images of a disfigured landscape of war, Yacoub’s “Summer 88” (2006) circulates the negative affects associated with war and brings an affective friction into the photographs themselves.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.