Press information

Karina Nimmerfall

Indirect Interviews with Women

Infos

Press preview

17.5.2018, 11 am

Opening

18.5.2018, 6 pm

Duration

19.5.–1.7.2018

Opening hours

Tue – Sun, 10 am to 5 pm

Curated by

Reinhard Braun

The exhibition is accompanied by an eponymous publication in the Edition Camera Austria.

The exhibition is part of Architektursommer 2018

Press downloads

Press Information

The abdication of Edward VIII in the year 1936, due to his wish to marry the American Wallis Simpson, triggered a veritable constitutional crisis in Great Britain. From this ensued distrust in the British press, which held back the news in a kind of gesture of self-censorship until the day of abdication itself, although rumors had been circulating for some time already. Marriage to a commoner and the resulting debate shed light on the biases and myths inherent to relations between the general public and the royal family. In the scope of this debate, it was evident that British sociology knew next to nothing about the wishes, fears, and views of the population. It was in this climate that the author and journalist Charles Madge wrote a letter to the newspaper New Statesman about an ongoing project on the anthropology of British society. A group of artists, authors, and documentary filmmakers had already founded an organization meant to establish a new science “of ourselves”: Mass Observation. The project was initiated based on an impression of a complacent press and a political sphere uninterested in the needs of the working class. Nonetheless, the work of Mass Observation was controversial from the outset. In 1937, an article was already published in The Spectator stating: “Scientifically, they’re about as valuable as a chimpanzees tea party at the zoo.” Yet when the war began, Mass Observation demonstrated their expertise in a publication called War Begins at Home, published in 1940. In the book, they documented the first four months of the war: the ramifications of power outages, the neuroses from the air raids, the pacification efforts on the part of the administration and politics, and the class conflicts during evacuations. During this period, Mass Observation worked for the Ministry of Information, which goes to show, among other things, that around 1940 the connections to art and literature had largely disintegrated. However, the project must still be seen in the context of British documentarism of the 1930s, especially documentary film, with John Grierson deserving mention here as the most notable filmmaker of that period. Mass Observation thus arose during the era of late modernism, which was characterized by a strong interest in the connection between art and reality and which displayed a new interest in everyday life.

Karina Nimmerfall, for her project “Indirect Interviews with Women,” researched material from the archive of Mass Observation at the University of Sussex, which was likewise established during the war, in 1941, the period of the London bombings. Her interest goes back to a survey of women regarding their perception of their current living situation at the time and their ideas for improving postwar housing. The Austrian artist, who lives in Cologne and Berlin, has long been exploring issues of architecture and housing: already in 2015, her book 1953: Possible Scenarios of a Discontinued Future was published in the Edition Camera Austria. It thematizes Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander’s master plan for a new, modernist social utopia—a city within a city for 17,000 inhabitants in Chavez Ravine, a neighborhood situated to the northwest of downtown Los Angeles. The project was never built after it sparked a local housing war orchestrated by private construction companies, real-estate lobbyists, and the media. This local war waged by means of anti-communist hysteria and propaganda ultimately impacted housing programs throughout the entire US and accordingly marked a turning point in nationwide housing and urban development. Already in this project Nimmerfall explored the correlations between certain historical utopias and our present day, which was described as a time after history when utopias were, in a best-case scenario, viewed as having failed, and when rampantly raging politics of right-wing populism want to turn back time and dismantle emancipatory achievements, such as that of the Movement of 1968. Karina Nimmerfall thus situates her query of social blueprints, their history, and their (provoked) collapse into a charged engagement with a present that asserts itself as lacking alternatives and aspires to banish criticism and counter-models into the realm of sentimental naïvety.

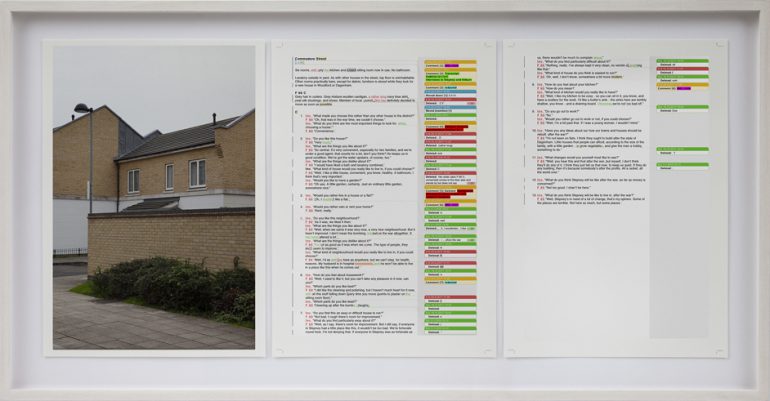

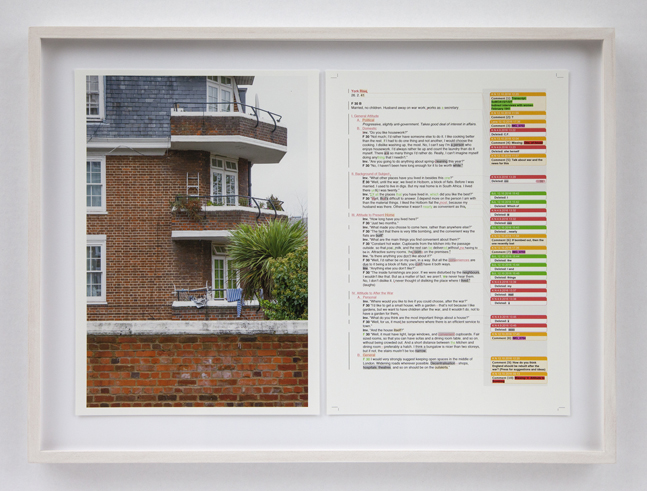

In “Indirect Interviews with Women,” transcripts of original interviews, including all current corrections, amendments, comments, and notes, are combined with photographs of the respective neighborhoods and housing complexes where the interviews originally took place, showing these buildings in their present state. “Possible Scenarios of a Discontinued Future” could actually be the subtitle of this work: it confronts a segment of historical reality with a present, although this alignment or, perhaps better said, this juxtaposition omits a large period of time. In fact, it omits many discontinuous shifts in thinking, in lifestyle, from affluence to poverty, from technology to body image, and so forth. Essentially, this work consists of a well-calculated void—despite it being founded on very comprehensive research—which we as beholders of the sixty-five works have to fill.

Of what do the statements made by the women in these interviews remind us? Do we still share any of their dreams? Can we identify similar social tensions today as those mentioned there? Which gender relations are inherent to the women’s statements? For it must be noted that the women were mainly asked about their relationship to running a household, their wishes pertaining to living space for the family—house or apartment—or to a garden. Blatantly obvious here is the primary localization of women in households, in private ones. One of the questionnaires, however, does pose the questions: “Do you go out to work?” or “Would you rather go out to work or not, if you could choose?” This is, of course, aimed to identify a desire in women to do more than just housework. However, the response to these questions was “No” in most cases, meaning that being gainfully employed was not (or hardly) considered an option in their life plans. Discernible from their replies to questions about their desired future housing forms, most expressed skepticism about modernism, especially as pertains to the idea that the government might seriously take these wishes into consideration. An insurmountable gap between the British women of the early 1940s and the politics of that era is tangible: they basically saw no place for themselves in politics, neither as far as their views were concerned, nor in terms of exercising codetermination of such political policy.

Which cultural, ideological, and political ideas and visions fill the space and the time between the interviews and the photographs—on the basis of the perspective of a present in which a referendum for the protection of non-smokers receives considerably more signatures than one for equal opportunities for women in our society? Does Karina Nimmerfall’s project not almost seduce us into making such comparisons between our everyday life and that of history, into a recapitulation of the revolts of the everyday against the ignorance of politics, having led to the slogan of everything being political? How might questions asked by interviewers in the 1970s have differed? What would they target today?

Mass Observation stayed active into the early 1950s, and then again starting in 1981 up to the present. So some issues could be settled thanks to the broad archival inventory, at least those pertaining to Great Britain. Yet since Nimmerfall’s interest lies not in a retelling but rather in a confrontation, the project proves to be something of an assemblage. “Now, in a strict sense, there are neither complete transformations nor absolute facts. So one must create ‘experimentation conditions’ in order to show the non-ideal character of history, that is, the fundamental impurity—the incompleteness, the ‘inconsistency,’ the conflictual and fragmentary character—of all historical transformation” (Georges Didi-Huberman). Her own practice as photographic artist, in conjunction with the historical statements by women in London from the year 1941, fosters an experimental space that visualizes the incompleteness and inconsistency of historical transformation. “There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation” (Jacques Derrida). Karina Nimmerfall links the constitution of the (gaps in) history with a question of how reconstruction might be possible based on the archive, and also, not to be forgotten, with her artistic practice. Her images likewise speak, in a different way, of a state of housing, of urban planning, or urban development. It is unmistakable how signs of affluence and decline are inscribed into her photographs, which are utterly devoid of people. The people missing from her pictures are the interviewed women, who we could (should?) insert—in imagination—into the photographs. This gives rise to an almost dialectical image: “Where thinking comes to a standstill in a constellation saturated with tensions—there the dialectical image appears. It is the caesura in the movement of thought. … It is to be found, in a word, where the tension between dialectical opposites is greatest” (Walter Benjamin). Is it not such opposites—the greatest ones conceivable—that Nimmerfall arranges for us in her tableaus, so as to bring thought to a standstill in the sense that it constantly wants to explain one thing away with another? Yet the assemblages in “Indirect Interviews with Women” are not occupied with explaining; they span time and space as contradictions, as a collision, as a conflict that cannot be resolved. Citing Bertolt Brecht, one could say that the effect of their work, like that of any assemblage, rests in submerging the message that it supposedly conveys in crisis. But which (or whose) crisis does this imply?

The twentieth century, according to Alain Badiou, witnessed a deep mutation of the question of “We,” seeking common ground, seeking community—a century in which, as André Malraux noted, politics became a tragedy, a century of passion for the real, a century engaged in the paradigm of war, a century of the production of the new, a century of the wandering, “a return which, prior to the wandering, did not exist as a return.” (Alain Badiou), a century that ended with the dominion of artificial individualism.

“Inv. ‘How do you feel about housework?’

F 40 ‘I don’t know.’

Inv. ‘Which parts do you like best?’

F 40 ‘I don’t know.’

Inv. ‘Which parts do you like least?’

F 40 ‘I don’t know.’”

This forty-year-old woman nearly completely evades the whole interview by giving her same reply over and over: “I don’t know.” In what way is she still part of the archive, part of history, part of a wandering, of a quest, of a tragedy which she does not name, simply by refusing to answer; yet she gives a flash of it by drafting a space where anything possible can be interpreted there, a space that remains open to countless conceivable answers, that opens up just as many countless options and speculations. The passion of the archive itself and also the passion for the real are, in this stance of resistance or indifference, suspended as it were. Is she anticipating that these interviews will set the archive against one of its possible futures that the archive itself could never imagine, or that could not be imagined from the archive itself? Would this not imply submerging these passions in a crisis, not anticipating the return but alluding to the continued wandering on which the century will yet embark? The concentration camps have not yet been liberated. So many millions of people have not yet died in this century. The caesura, the fissures, divisions, the rifts that Nimmerfall leaves open for us in the gaps between her present-day images and the voices of a past, of a very specific past—it is sometimes hard not to fill all this with the darkness traversed by the wanderings and passions of the twentieth century.

Reinhard Braun

Karina Nimmerfall is a visual artist and professor of cross-disciplinary artistic-media practice and theory in the Institute of Art and Art Theory at the University of Cologne (DE). She explores in particular the relationship between architecture, urban space, and media, as well as their conditions within cultural, political, and ideological representations. She has participated in numerous exhibitions, including MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles (US); Kunsthaus, Graz (AT); BAWAG Contemporary, Vienna (AT); Kasseler Kunstverein, Kassel (DE); Göteborgs Konsthall, Gothenburg (SE); Landesgalerie Linz (AT); Bukarest Biennale 3, Bucharest (RO); and the 8th Havanna Biennale (CU).

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.