Press information

Heidi Specker: Fotografie

Infos

Ed. by Reinhard Braun.

Acompanying the eponymous exhibition, Camera Austria, Graz, 14.7. – 26.8.2018.

With a contribution by Reinhard Braun and Heidi Specker (ger./eng.).

Edition Camera Austria, Graz 2018.

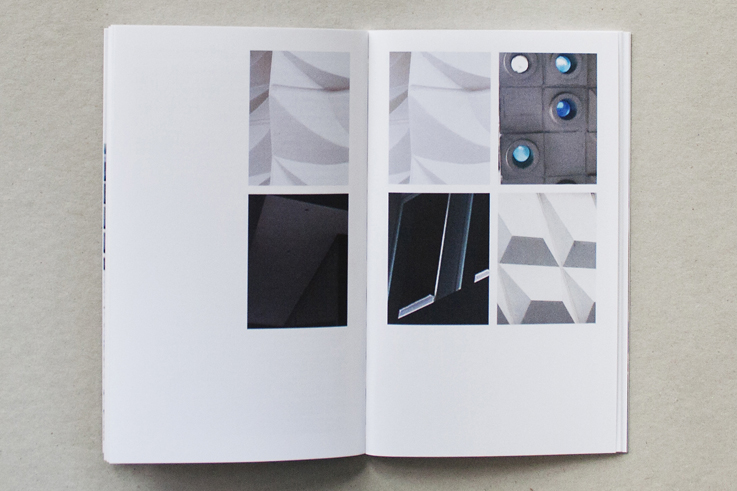

32 pages, 13 × 21 cm, 20 color illustrations.

€10.– / ISBN 978-3-902911-45-2

Press downloads

Press Information

Excerpt from: Reinhard Braun, Heidi Specker, “On the Being-Together of Images”

To the question “What is the city made of?” Heidi Specker “responded” in 1998 with the series “TEILCHENTHEORIE” (PARTICLE THEORY), with details from architectural surfaces of Berlin architecture, with a liberation of recurring façade decor from its original architectonic coherence and mélange, which set these details free, made them different, useless, placeless, beautiful, but also abstract and, at the same time, both antisocial and empathic or compassionate. The response to the issue of totality is its dissolution, a theory of particles. The city is composed of surfaces; we can behold or ignore them, perceive the creative drive or not, like the vacant lots. Something is there to be seen, or maybe not. Back then just as now, thirty years later. A typology arose that, due to the renovations that have since been initiated, is probably already in the process of disappearing again, yet it still retains its validity. Today the series evokes no sense of nostalgia, though it does to a certain extent represent a survey of the past, of the history of a city that is associated with its specific architecture like hardly any other. This survey still remains subjective and objective at once, beautiful and repellent at once, reconstructive and utopian at once.

In the year 1934, Walter Benjamin held a lecture at the Institute for the Study of Fascism in Paris, which was published under the title “The Author as Producer.” In this lecture, Benjamin stated: “It [the photography of Neue Sachlichkeit] becomes ever more nuancé, ever more modern; and the result is that it can no longer record a tenement block or a refuse heap without transfiguring it. Needless to say, photography is unable to con-vey anything about a power station or a cable factory other than, ‘What a beautiful world!’ . . . For it has succeeded in transforming even abject poverty—by apprehending it in a fashionably perfected manner—into an object of enjoyment.”¹ “TEILCHENTHEORIE” introduces a method, demonstrates a method that moves—in a fragile, fleeting, contested, uncertain, and yet manifest way—along a boundary between poetry and soberness. And this technique speaks differently about the world than in its glorification, even when the pictures are beautiful, or perhaps precisely when they are beautiful, because they are beautiful for being subversive, because they separate, divide, thus dismissing the whole—the world, the city—removing it from sight, taking it out of sight.

“TEILCHENTHEORIE,” in any case, and this may be asserted without risk, is not representative. The parts do not represent a whole, for the parts are simply parts on which light is shed. Each individual part receives attention, in a non-hierarchical way, a block of images, a being-together of images—a community of images?

Fifteen years after “TEILCHENTHEORIE,” Heidi Specker took photographs for her book THREE WOMEN on a trip with a girlfriend wearing a blue-red headscarf with white flowers. Almost only this headscarf is visible, almost only this white floral pattern—daisies—against the blue and the red background, along with a suggestion of a pair of glasses, a forelock stirring in the wind, the sun, a stairway in the background. At the sea? A castle? Yet, really, this is not important; it is the headscarf that captures the gaze and the picture. “Beautiful images or ideas that are preserved by the picture for no other reason than because they only ever exist in the picture, because they have only ever been created by the picture.”² The headscarf itself becomes a surface that outshines everything, that blends out everything else, that divests and reinstates all meaning, an ornament, a kind of décor, which inscribes itself into what may be an unforgettable moment, or into which an unforgettable moment may have been inscribed, or which appears to be such a moment because photography has ascribed it to it and inscribed it in this very moment—a surface like that of architecture, like the décor of architecture, beautiful, recurring, unique and banal, structuring and random, constructive and transient, all at once. The headscarf, the woman, and the sun, and perhaps even more than the photographer could see or really saw, or maybe did actually see. The image comes together; what can come together does so, thus resulting in an image; what the pho-tographer has evoked comes together, yet without her being able to fully assert control. A fragile encounter, a perception, characterized by uncertainty—or even better, by caution or prudence, maybe even by respect (an anachronistic idea, perhaps fallen out of time, yet does not photography itself constantly fall out of time, penetrate time, in order to activate some-thing within us to which we would have no other relationship except that aroused by the photographic image itself?). “Touch me with a real touch, one that is restrained, nonappropriating and nonidentifying.”³ Yet this touch does not take place entirely randomly; it is first staged by photography, which in turn embodies the practice of the photographer. But does the act of staging, the making, the producing and creating of an image, imply at the same time that we possess it (in a more global rather than proprietary sense), or that we already knew it before it was taken? Does this fragile manifestation of a touch, as that which photography may appear to be, not instead mean liberating the images, releasing them, sharing them?

¹ Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2: Part 2, 1931–1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. (Cambridge, MA, and London: Belknap Press, 1999), p. 775.

² Translated from Gilles Deleuze, Unterhandlungen: 1972–1990 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1993), p. 116.

³ Jean-Luc Nancy, Noli Me Tangere: On the Raising of the Body, trans. Sarah Clift, Pascale-Anne Brault, and Michael Naas (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), p. 50.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.