Camera Austria International

143 | 2018

- ABIGAIL SOLOMON-GODEAU

Art Photography in the Age of Catastrophe - DUNCAN FORBES

Beyond Melodrama: Photography and Mexico ’68 - LARA BALADI

“Nothing Is Well in Egypt”

Below and Above: The Bird’s-Eye View of Tahrir Square - MARINA GRŽINIĆ

Images of Violence, or the Violence of Neoliberal Necrocapitalism - ANA TEIXEIRA PINTO

What’s in an Image? - DINA AL-KASSIM

Maria Eichhorn’s Japanese Mapplethorpe - OMAR KHOLEIF

Imagining Sound as Image

Lawrence Abu Hamdan and the Politics of Visuality - CHRISTIAN HÖLLER

In the Maelstrom of Images

On the Absorbent Power of Contemporary Image Production

- TIMOTHY DRUCKREY

Astride “Post-History” and the “Instant Archive” - SELECTED BY …

Preface

Ever since the first symposion on photography in 1979, the publication of which served as a departure point for the magazine Camera Austria International, Camera Austria’s work has been characterized by an intensive investigation into the relationship between text and image, theory and visual practice. Beginning with the fourth issue, the magazine regularly published the lectures of these symposia, the last of which, “Agents and Agencies,” took place in 1997. Timothy Druckrey and Christian Höller, two of this issue’s authors, took part in the 1997 symposion; their essays highlighted the growing influence of cultural and visual studies as well as the questions media studies posed regarding the debates waged over photography.

Camera Austria International 143 | 2018

Preface

Ever since the first symposion on photography in 1979, the publication of which served as a departure point for the magazine Camera Austria International, Camera Austria’s work has been characterized by an intensive investigation into the relationship between text and image, theory and visual practice. Beginning with the fourth issue, the magazine regularly published the lectures of these symposia, the last of which, “Agents and Agencies,” took place in 1997.¹ Timothy Druckrey and Christian Höller, two of this issue’s authors, took part in the 1997 symposion; their essays highlighted the growing influence of cultural and visual studies as well as the questions media studies posed regarding the debates waged over photography.

This broadening of the contexts in which the photographic image plays a role and undergoes theoretical examination can also, however, be traced back to the beginnings of the symposia. Diverging or opposing positions were placed in relation to one another to widen the purview of the debate over photography on an ongoing basis—in the cultural sciences, visual studies, urbanism research, architecture, literature and film studies, philosophy, media theory, semiotics, the politics of representation, political activism, feminist theory, postcolonial studies, etc. First and foremost, however, the symposia were also a locus of exchange between theory and artistic practice. Today, this transdisciplinarity or even postdisciplinarity is taken for granted. In this regard, from a contemporary point of view, it appears that during the symposia on photography it wasn’t so much existing agreements that came to expression, but a polyphony of disagreement, discrepancy, and dissent corresponding to the simultaneous, albeit opposing perspectives on the photographic image.

In October 2018, a symposium on photography will once again take place in collaboration with steirischer herbst, dedicated to the theme of the “Violence of Images” and following in this tradition of the polyphony and expansion of discourses. This symposium again brings together artists and experts from various disciplines: Christine Frisinghelli, Marina Gržinić, Ana Hoffner, Tom Holert, Jakub Majmurek, Guy Mannes-Abbott, Ines Schaber, Ana Teixeira Pinto, and Ala Younis. In contrast to the past, however, we have decided to publish this issue of Camera Austria International, which is deliberately conceived as a text and theory issue, concurrently with the symposion as a kind of ground-preparing reader. In an intersection between magazine and symposion, some of the participants will also publish an essay in this issue. Other lecturers and authors have already published in the magazine, some of them having cooperated with Camera Austria for many years. The question we posed to the invited authors was simple: what themes and reflections on photographic subjects—whether they be artistic or related to everyday culture—are currently at the top of their agenda?

We’re fascinated by the result, a panorama of observations on and insight into visual cultures: art photography in the age of catastrophe; questions of censorship and of the visual representation of revolution; the question as to what, if anything, can be gained from racialized images; the way in which right-wing authoritarian politics are expressed in conventional imagery; the forensics and representability of the sonic; the phenomenon of demobilization through images, and the resulting visual “instant archive.”

As a team that’s been working together on the production of this magazine for many years, we are, of course, well aware that reading and researching mean something completely different today than even a few years ago. Much of the time, it’s all about short, fast information, summaries, excerpts to move through quickly. Knowledge is supposed to come to us—prepared, explained, commented upon, usable. In a time in which anti-intellectualism is on the rise, however, it seems appropriate for this very reason to slow down and branch out, elaborate, become more comprehensive. In agreement with Stuart Hall, we believe that reality is not something that can be understood easily. And the texts are important in this effort against reducing photographic images to things that are merely glanced at in passing or while turning the page. Images require time, just as texts require time to be read and understood; each prepare us for a slowness that “would be a time that takes time, that is, a time that takes the time for the slowness of the investigation and of the architectonics” (Alain Badiou). This is the time in which texts meet images: “Images and words collide so that thought has its place in the visual” (Georges Didi-Huberman). This place, or rather, this moment of collision could also mark the political movement of images, their politicization; it could also shed light on the visualization of a politics that has replaced thought with allegation. How do the ways in which the visible is contingent on the word manifest themselves; what regulation in the relationship between knowing and not knowing are images subjected to; how can a practice such as representation be maintained when the images no longer primarily depict something, but are integrated into events in various ensembles?

We’ve developed the current issue in the context of these questions in the hope of reaching our allies for the idea of the detailed, the scrupulously researched, and the comprehensive—while addressing the history of Camera Austria and bringing it up to date. Accompanying the texts in this issue is an expanded image section that we’ve developed in close cooperation with the authors who have long accompanied and left their mark on Camera Austria, and who were invited to propose artists whose work they’d like to share with the readers of Camera Austria International. We’re pleased that the contributions presented here offer a multi-faceted insight into current positions in art photography, one that’s proven unexpected, even to us.

Reinhard Braun and the Camera Austria Team

September 2018

1 And on a less regular basis thereafter: “Positions of Japanese Photography” (2003) accompanying the first exhibition in the new space of the Iron House Graz to mark the opening of the Kunsthaus Graz, “Pierre Bourdieus Blick auf die Gesellschaftliche Welt” (“Pierre Bourdieu’s View of the Social World,” 2004), as well as the Symposion on Photography XX, concurrent with the publication of Camera Austria International no. 100/2007, which focused on the South African Market Photo Workshop, cofounded by the recently deceased David Goldblatt.

Cover: Montage of various contributions to the magazine. Copyright: Satz & Sätze, Graz.

Entries

-

ABIGAIL SOLOMON-GODEAU

Art Photography in the Age of Catastrophe

The invitation to write an essay for Camera Austria International was especially gratifying because the choice of subject was mine, the only proviso being that I address a photographic subject I consider to be of importance. Thus, I proposed the subject of a book project I have been working on for something like ten years with the working title I’ve used for this essay. Consequently, what follows should be considered as a summary of those issues and questions that this artistic practice raises and as they have been discussed in some of the relevant literature—primarily anglophone—indicated in my notes. Various issues present themselves when art photography takes on, as it were, the catastrophic—whether natural (e.g., earthquake, tsunami) or man-made (e.g., war, ecocide). A partial list would include the influence of other practices on this recent avatar of art photography, such as photojournalism, documentary photography, and war photography. But other relevant developments are a consequence of new image technologies like digitalization and those that permit the mega-sizing of prints, the near-total assimilation of photographic work into the constantly expanding art world and its various apparatuses, and the perennial questions pivoting on the politics and ethics of photographic representation. And while recent art photography related to catastrophe could and should be understood as having attributes that reveal something about our contemporary culture, once such a relation is posited, these daunting topics and questions—all interrelated—immediately present themselves as inextricable from the subject of analysis. . . .

Depending on national or regional vantage points (so to speak), certain wars are imaged, while others are not. Unrepresented catastrophes, such as the Armenian genocide, are at risk of discursive invisibility and official denial, especially because since the twentieth century, photographic evidence has been popularly understood as the gold standard for the establishment of proof. Michel Guerrin points out that in 1968, while the American war waged in Vietnam, there were 400 American photojournalists covering the war; in 1982, there were two British photojournalists covering the Falklands War; and the US censorship of imagery of the first Gulf War has rendered invisible its approximately 200,000 victims.¹1 Michel Guerrin, “Crise du reportage de guerre,” cited in Dominique Baqué, L’Effroi du présent: Figurer la violence (Paris: Flammarion, 2009). On the occlusion of the victims of the Gulf War, see John Taylor, Body Horror: Photojournalism, Catastrophe and War (New York: New York University Press, 1998).

Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 11–16.

-

DUNCAN FORBES

Beyond Melodrama: Photography and Mexico ’68

Shortly after 6 p.m. on October 2, 1968, flares lit up the night sky above a protesting body of around 10,000 students and workers in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco, a working-class district in Mexico City. Small in comparison with earlier manifestations, the gathering was the latest in opposition to the repressive and paranoid authority of President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and his ruling party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI). The demonstration celebrated three months of student organization against state coercion with the aim of reconstituting Mexican democracy. But coming ten days before the inaugural ceremony of Mexico’s Summer Olympics—the first Third World nation to stage the event—and with the world’s media in attendance, Díaz Ordaz and his Interior Minister, Luis Echeverría Álvarez, moved to clamp down on the protestors. The illumination by flare was a signal, and sharpshooters positioned in the buildings around the Plaza opened fire on the crowd. In the ensuing mayhem, up to five hundred students, workers, and residents were either shot or bayoneted to death. Many hundreds more were wounded and interned in the Military Camp One. . . .

The truth of ’68 in Mexico is still today an open question. Its memory is subject to perpetual interrogation and reconstruction. This places a peculiar burden on its evidential legacy, including photographs, a legacy that in the last ten years has been intensively investigated.¹ In 2016, I visited the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), which makes extensive use of photography in its displays to explore the course of events on that dreadful night in October. The installation included a long strip of portraits (full-length mug shots might be a more accurate description) of imprisoned students, hung in a light box across two walls. The photographs had been taken in 1968 by a photographer of the Ministry for the Interior and sold by his family after his death to UNAM in late 2000. Photography intended to be repressive had been repurposed. Mug shots of arrested students, scared and defiant, now took on an honorific character.1 See especially Alberto del Castillo’s exhaustive study, La Fotografía y la construcción de un imaginario: ensayo sobre el movimiento estudiantil de 1968 (Mexico: Instituto Mora and UNAM, 2012).

Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 16–21.

-

LARA BALADI

“Nothing Is Well in Egypt”

Below and Above: The Bird’s-Eye View of Tahrir SquarePierre Sioufi was larger than life, literally and metaphorically. His belly always preceded him. An avid collector, his appetite was not only big for food. It was Pierre who introduced me, in the early days of eBay, to the magic of exchanging treasures online. His diverse collection ranged from uncanny objects to images, photos, postcards, and more. Defeating time, slowly devoured by dust, a pile of out-of-print posters from the golden days of Egyptian cinema was stacked haphazardly at the entrance of his apartment in spite of their value. He gave me the impression that Egypt’s history had left him behind. A priori disillusioned, there was a certain nonchalance to this sensitive, gentle, yet almost gigantic man. Pierre might have taken his passion further and contributed to preserving some of the most creative visual productions of his time. He moved smoothly through Cairo’s organized chaos. Caught between two major historical periods, Nasserism and the 2011 uprisings in Tahrir Square, Pierre like others of his generation, a sacrificed generation, grew up in a cultural void. They paid the price of living during the major shutdown that Egypt experienced following the 1952 revolution, oscillating between the nostalgia for a glorious past about which their parents reminisced and a melancholic longing for a hopeful future.

In January 2011, during the eighteen days that toppled President Hosni Mubarak, a bird’s-eye view of the uprisings that took place in Tahrir Square was constantly displayed, if not full screen, in the corner of every TV channel covering the events in Egypt. In a very similar way as “the same infinite-loop video of the planes’ impact flickered over the television screens and the photographic coverage [of 9/11] was restricted to only a few types of images,”¹ the bird’s-eye view of Tahrir overwrote all other documentation of the uprisings, immediately becoming a transnational icon and symbol for regained hope, freedom, and solidarity. Whether televised or still, this image of a packed Tahrir seen from the sky, the vibrancy, the energy, the ongoing movement of the crowd below, cut across media in a contagious fever rallying many more people worldwide in protests against capitalism, oppression, and dictatorship.1 Florian Ebner, “On Stereotypes and Icons: Rhetoric of the Image,” Bulletin, no. 13, March 2010, Braunschweig Museum of Photography, p. 9.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 22–27.

-

MARINA GRŽINIĆ

Images of Violence, or the Violence of Neoliberal Necrocapitalism

My interest in this text is to connect racism with visual narratives, °“trophy” artifacts, and culture. The first part of the text looks at racism from a historical perspective, showing a horrifying trajectory of structural racism that reproduces itself almost always circularly from a pseudoscientific (biological) racism, “progressing” toward “cultural racism” to “return” again to “scientific racism,” though then coined “intellectual racism.” In the second part of the text, artistic projects and institutions are put in relation to this trajectory.

Images with violent content are always historical, as what is seen as violent is constructed and is violently managed; therefore nothing is natural in relation to violence. What will be defined as violent is always an outcome of violent hegemonic processes. Seeing images of killings can provoke our rebellion and our insurgencies, or we can be paralyzed by our normativized occidental lives.

Europe and the global neoliberal capitalist system in general are well attuned to the hierarchization, control, and management processes of the present neoliberal capitalist states. Especially under attack are migrants and all those not considered to be “natural” parts of the neoliberal capitalist national body in the West: asylum-seekers and refugees escaping war-torn parts of the global world (the Middle East, Africa), from conflicts induced by capital and imperial management. When coming to Europe, they are prevented from entering the European Union due to a system of control and biopolitics (which is in fact necropolitics). They are expulsed on the grounds of EU and national laws, and thus legally deported. The EU bases its “vision of civilization” on a system of procedures and acts that are “blind” toward discrimination and supportive of racist cleansing. What we have here is structural and class racism being normalized throughout the entire territory of the EU.

On the other side and at the same time, we can see, for example, the last election campaign in Austria, with posters by the Freedom Party (FPÖ) containing blatantly racist and fascist slogans and images. Such posters target those who, in the logics of “blood and soil,” are not considered to be “Austrian” enough and are therefore supposedly “endangering the national substance, with their improper use of the German language,” and the like.Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 27–33.

-

ANA TEIXEIRA PINTO

What’s in an Image?

On February 2, 2017, a young black man, Théodore (Théo) Luhaka, twenty-two years old at the time, was interpellated by police as he walked out of an underpass in the French suburb of Aulnay-sous-Bois. The video of the accident shows the ensuing struggle, with several police officers manhandling the young man as he tried to defend himself, succeeding in breaking free at one point, only to be violently battered with truncheons. The police officers used tear gas at extreme close range and managed to wrestle Théo to the ground, but he grappled, loosened their grip, and raised himself up, at which point an officer thrust his truncheon into the young man’s rectum. Stung by acute pain, Théo fell to the ground and was handcuffed by police. Six months later, the young man, who suffered a ruptured colon, was still wearing a colostomy bag.

One year after the events of February 2, the station Europe 1 released the video, captured by security cameras at the site, changing the public perception of the case. Marketed as “la video choc qui change tout” (the shock video which changes everything), the footage went viral. Upon viewing the clip, the commentariat began to switch its position from mildly sympathetic to outright dismissive. Viewers were repeatedly told that Théo was costaud (sturdy), that he resisted the officer’s commands, that the police officers were simply “doing their job,” and, most importantly, that the video footage did not support Théo’s claim that he had been raped by the officers involved (the officer’s gesture is extremely fast and the footage is choppy because digital cameras with a low frame rate do not capture high-speed motion properly; that said, it beggars belief that the rectal rupture could have resulted from an unintentional action).

It is not my intention to denounce the police brutality or the institutional racism that supports it—though that certainly needs doing. Police violence, even when it takes such an extreme form, is both widespread and institutionally sanctioned, and this event is in no way exceptional—on the contrary, police brutality in relation to racialized subjects is wholly normalized. What is singular about the affaire Théo, as the case became known, is the role played by the video footage in the subsequent narrativization of the event, and in the swaying of public opinion against, rather than in favor of, the victim. Hence my question: What is in an image?Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 33–38.

-

DINA AL-KASSIM

Maria Eichhorn’s Japanese Mapplethorpe

There is no writing which does not devise some means of protection, to protect against itself, against the writing by which the “subject” is himself threatened as he lets himself be written: as he exposes himself. (Jacques Derrida)¹

One among many figures of writing and auto-immunity, this description of the Mystic Writing Pad in Freud’s “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” (1920) leads Derrida to a series of reflections on a technology of writing that destines itself to erasure while supplying a master metaphor for Freud’s consideration of psychic inscription dependent upon censorship and forgetting. “Writing is unthinkable without repression. The condition for writing is that there be neither a permanent contact nor an absolute break between strata: the vigilance and failure of censorship.”² Derrida’s uptake of Freudian censorship leads him to this surprising coupling of vigilant self-defense and surrender to exposure in a reading of what is not a metaphor but a writing machine, a peculiar materialization of the “differantial strictures” of the psyche, its memory, and erasure.

Derrida’s account of the Mystic Writing Pad draws our attention to an oscillation of self-exposure poised between actively letting oneself be written while passively resisting being consumed in the act. The “self” divides as an effect of the spacing of repetition and of the temporal accumulation and delay of inscription; it develops. The hesitation of resistance and surrender materialized in the Mystic Writing Pad reappears in Maria Eichhorn’s performance and photography project, “Prohibited Imports” (2003–ongoing), an aesthetic transaction with state censorship produced by repeated mailing of censurable material—“A book of historical photographs from the Kinsey Institute, catalogs of Wolfgang Tillmans . . . Jeff Koons,” and Robert Mapplethorpe—to the Masataka Hayakawa Gallery in Tokyo. The mailings were intended to activate the Japanese customs authority and to instigate legal censorship with the promise to exhibit the resulting redacted pages, scoured by the censor’s “sand pen.” All images of genitalia were excised, while the scenarios and surrounding hands, scrota, hair, and skin remained largely untouched. To examine “Prohibited Imports” from the perspective of Derrida’s 1967 discussion of protection and exposure opens the vista of archival reframing. In particular, Eichhorn’s reframing of Mapplethorpe’s “Self-Portrait 1981,” censored, rhymes with Derrida’s reading of writing and censorship as exposure.1 Jacques Derrida, “Freud and the Scene of Writing,” in Writing and Difference, trans. and with an introduction and additional notes by Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), p. 224.

2 Ibid.Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 39–44.

-

OMAR KHOLEIF

Imagining Sound as Image

Lawrence Abu Hamdan and the Politics of VisualityIn the 1950s, the philosopher and theologian Henry Corbin studied Iranian Sufism, and specifically the writings of the Persian mystic Ibn Arabi. In his treatise, “Mundus imaginalis,”¹ Corbin derives from Sufi mystical beliefs an argument which critiques the notion of the imagination, and indeed the notion of the “imaginary.” His argument at the time was that the “imaginary” was rooted in the realms of what we could conjure through the limited means of the reality that we have come to understand, which we have become indoctrinated with (or at least that is how I choose to read it). In turn, he proposed an alternative word, the “imaginal.” Nearly fifty years later, Chiara Bottici pulls from the theories of the “imaginal” to argue that the imaginal is a condition that is strictly localized to and derived from “the image.” What do images tell us? What histories do they hold? How can we make visible that which is invisible from the political realm?

In her book Imaginal Politics, Bottici argues for a world where we have the potential to conjure our own images, to depart from the looping circuit of image culture that has been propagated by media organs saturating us with a visual vocabulary that prevents any other form of image culture from being constructed. The question then of the imaginal image brings me to the work of W. J. T. Mitchell, who in his book What Do Pictures Want? investigated the state of image culture in mass media and art history. He wondered: What do images want, and indeed demand of us? What if they have the potential to move, persuade us, and shift the ways in which we behave?

I have been influenced by Mitchell’s work since picking up this book and have been attempting to reconcile this question of the demands of images since image production has shifted and begun accelerating in the digital age. Within this framework, I have been questioning what could an imaginal space for images look like? Images that we have the agency to produce, images that we do not see? This in turn led me to the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan, a Lebanese-British artist and researcher whose entire practice around listening manifested in images that we could not, at first, see. These are images that demand a different kind of vocabulary, a unique sense of imagination to conjure up what they might do to us in terms of a “reality?”1 Henry Corbin, “Mundus Imaginalis or The Imaginary and the Imaginal,” trans. Ruth Horine, Spring 1972, pp. 1–13, https://archive.org/details/mundus_imaginalis_201512; see also Henry Corbin and Ralph Manheim, Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn Arabi, trans. Ralph Manheim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), esp. the preface by Harold Bloom.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 44–47.

-

CHRISTIAN HÖLLER

In the Maelstrom of Images

On the Absorbent Power of Contemporary Image ProductionThe feeling of being pulled into something. To witness events that one really would rather not have been so familiar with. Or to be entangled in circumstances that lead at best to something paralyzing, yes, something demobilizing, without much positive motivating force.

Jon Rafman frequently leads us to such scenes, which in turn often reference dubious contexts and liberate from such contexts obscure figurations: photographs of messy computer workstations, drunken bodies in a sorry state after student parties, or amusingly costumed mythical creatures slowly sinking into a mudhole. Rafman bundles, yes even composes, these found subjects originating from the depths of the Internet, specifically from diverse user forums, as artfully densified études about the kind of image power we are exposed to today, considering the strongly raging frenzy of documentation and posting.

Rafman’s films,¹ which are for the most part based on such apocryphal photo and video material, do not even pretend to (want to) maintain or express a critical distance to the content shown. They also largely suspend the illusion that we can create distance to seemingly undesirable states through a certain mode of staging. Conversely, these carefully assembled visual sheets do not indulge in mere fascination for what exists out there, in spellbound awe in face of everything offered by the digital world—with this world ready to fire at embarrassed-looking subjects, who do not really seem able to cope with, for better or for worse, this visual power. Rafman’s films, for instance “Still Life (Betamale)” (2013), “Mainsqueeze” (2014), or “Erysichthon” (2015), foster a sense of awe, but in a way that is not necessarily related to an empowerment of the viewers. Instead, this awe—and it remains open as to whether an emancipatory moment arises here as well—aims for a quality that manifests more and more in such images: namely, their absorbent power, as opposed to an activating, actively emanating power, meant to inspire viewers to adopt this or another critical stance. When confronted with images like a mud-bogged fox or a ridiculously masked, comic-esque figure placing two pistols to its temples, both found in “Still Life (Betamale),” then there is no simple way out of this perplexing confrontation. There is neither the option of the knee-jerk response of getting upset about or making fun of this strange alien world, nor of sedulously voyeuristic enjoyment.1 See the artist’s website: http://jonrafman.com. Also see Vera Tollmann and Jon Rafman, in after youtube: Gespräche, Portraits, Texte zum Musikvideo nach dem Internet, ed. Lars Henrik Gass, Christian Höller, and Jessica Manstetten (Cologne: StrzeleckiBooks, 2018), pp. 166–71.

Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 48–52.

-

TIMOTHY DRUCKREY

Astride “Post-History” and the “Instant Archive”

At almost every point in the history of representation, there has been and continues to be a necessary debate concerning the incessant presence and proliferation of images and their reverberations, dangers, pleasures, their populism and political effect—their role as propaganda and persuasion, excess or inevitability—no less their status as “real” in any sense. Indeed, the constant crisis of image culture comes in the reciprocity or clash between what is visual and what can be rendered visible and is as crucial to the history of photography as it is to the entire history of modernity’s inebriation with apparatuses that constituted visuality as its decisive, even universal, epistemological form.

This history has been deconstructed, reinforced, upended, and reinvented time after time and in ever-shifting implementations. Nevertheless, still intricate aspects of the intersections between representation, causality, history, technology, and the apparatus emerge in the kind of histories that have arisen in the past two decades. They demonstrate a deeper analytic understanding of the photographic¹ and of histories that have been obligated to grasp astonishing transformations in image production, image creation, image distribution, image reception, and the vast new territories that images inhabit.

In the two decades since the 1997 Camera Austria Symposion on Photography “Agents and Agencies,” several issues have come into play in the kinds of analysis it represented (particularly my contribution²). For me, it was a kind of millennial anxiety to account for the still immediate, even dramatic sweep of “new media” and the cultural reverberations of the kind of realities that would be enveloped in heated debates about the triumph of virtualization or the photo-optical illusions of computer-generated imagery (CGI).1 I use the term photographic to establish a difference between the practice of photography and the epistemological issue of the image itself as a purveyor of presumably reliable optical reality.

2 Timothy Druckrey, “Post-History, Post-Journalism, Post-Moderne,” Camera Austria International 62–63 (1998), pp. 17–25.Text feature in Camera Austria International 143/2018, pp. 52–57.

-

-

SELECTED BY …

The image section of this special issue has been developed in close cooperation with the authors who have long accompanied and left their mark on Camera Austria, and who were invited to propose artists whose work they’d like to share with the readers of Camera Austria International.

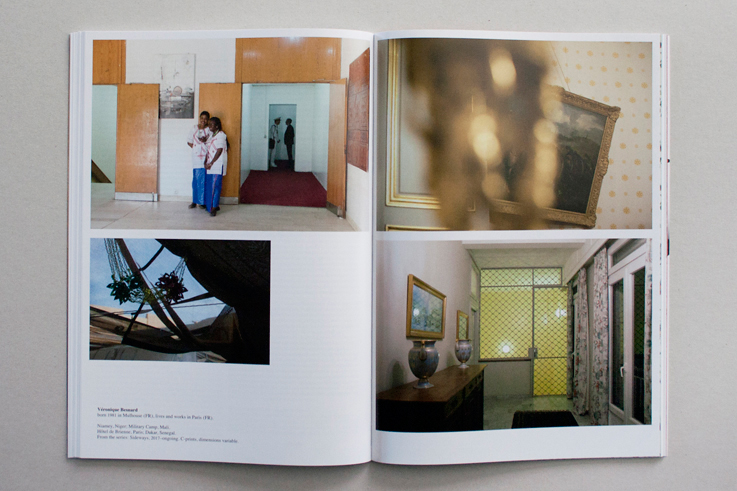

Sebastian Hau – Véronique Besnard

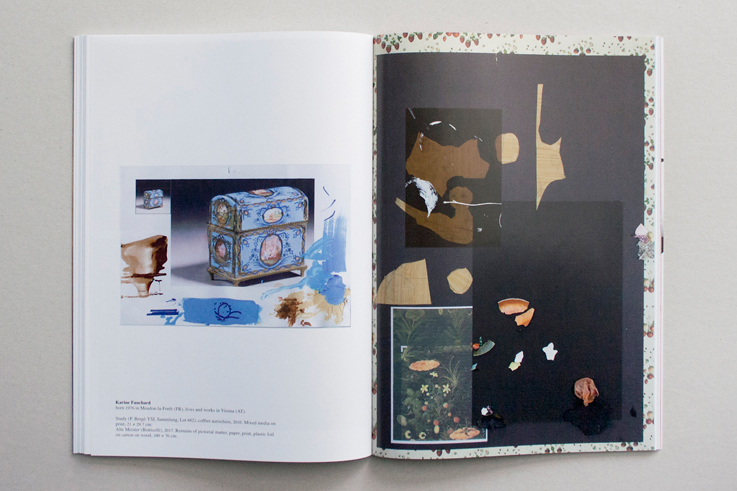

Anne Faucheret – Karine Fauchard

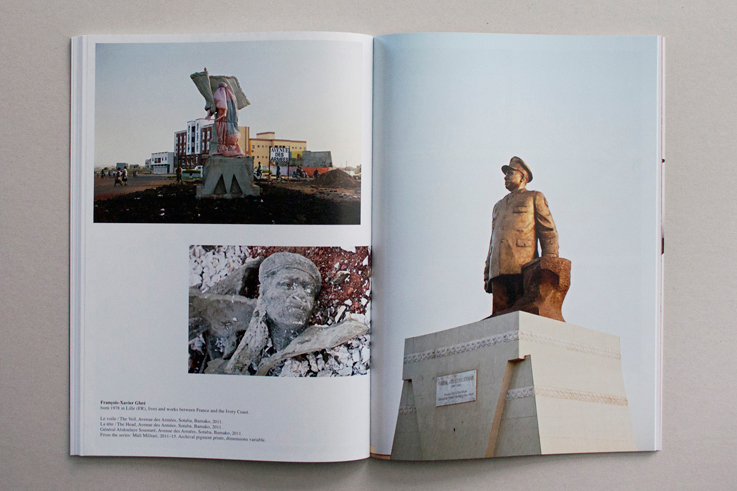

Luigi Fassi – François-Xavier Gbré

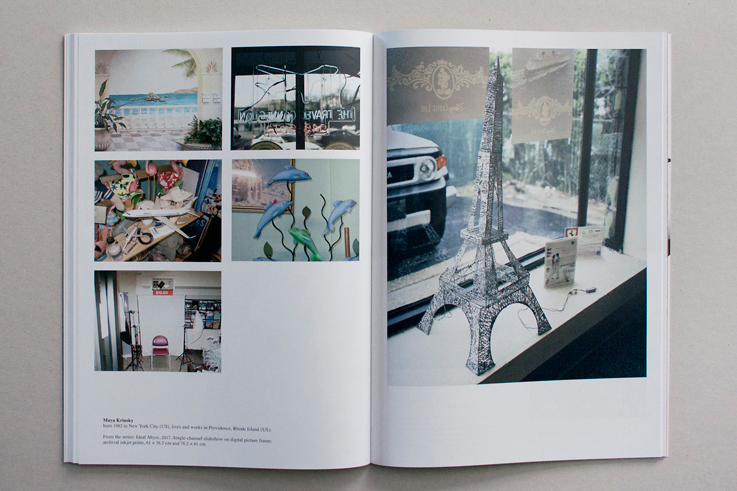

Nicolas Linnert – Maya Krinsky

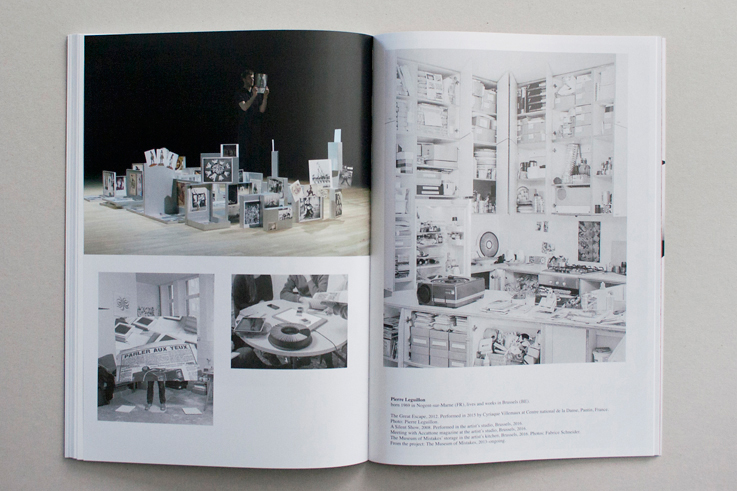

Mercedes Vicente – Pierre Leguillon

Taco Hidde Bakker – Bart Lunenburg

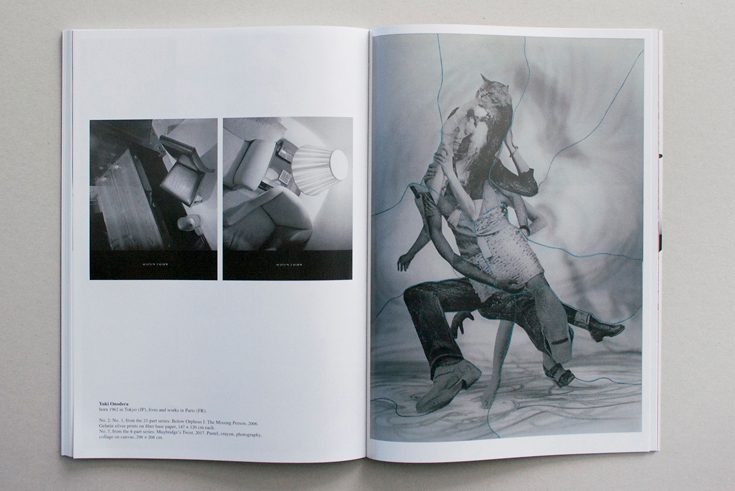

Michèle Cohen Hadria – Yuki Onodera

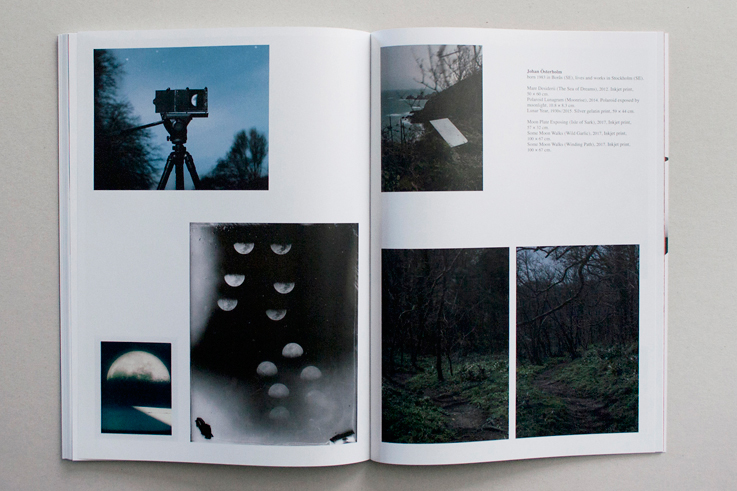

Jens Asthoff – Johan Österholm

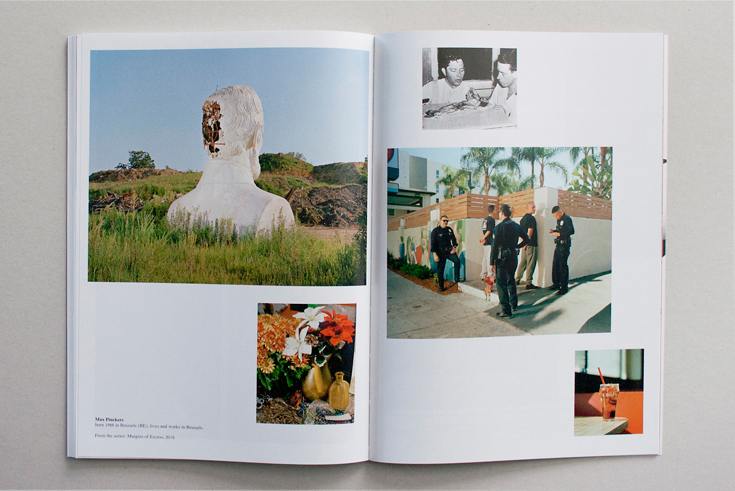

Fatoş Üstek – Max Pinckers

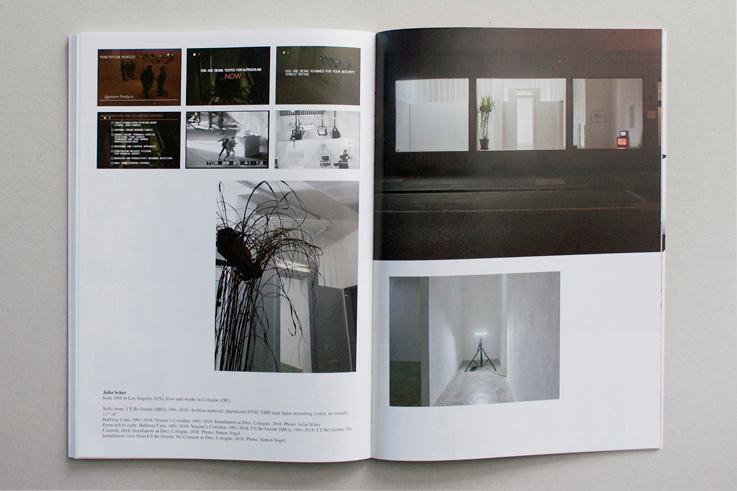

Moritz Scheper – Julia Scher

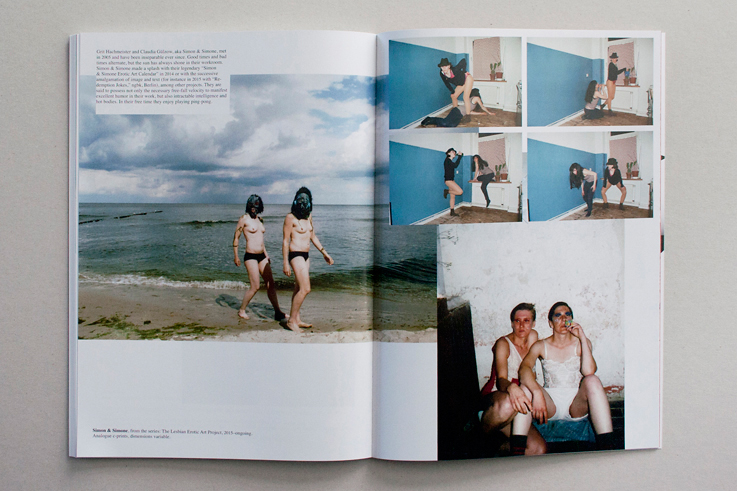

Susanne Holschbach – Simon & Simone

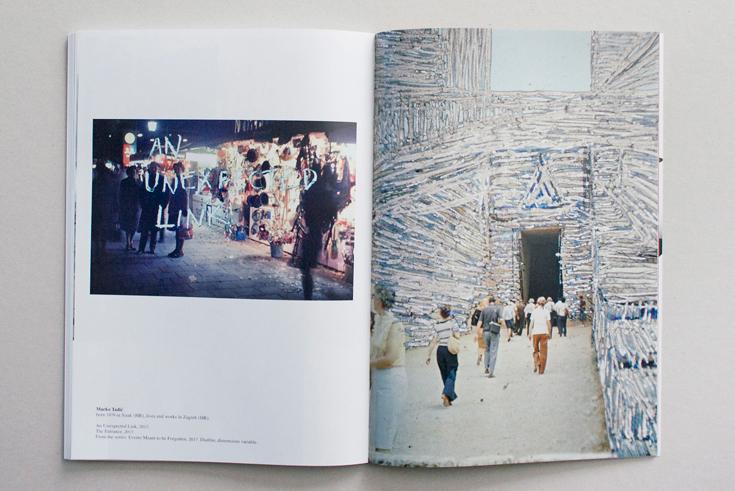

Sandra Križić Roban – Marko Tadić

Joanna Warsza – Franz Wanner

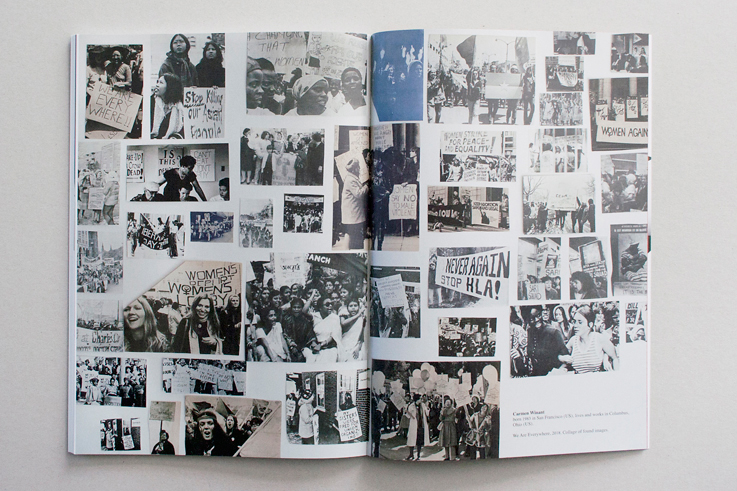

Matthew Rana – Carmen Winant -

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature VÉRONIQUE BESNARD in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 62–63.

-

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature KARINE FAUCHARD in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 64–65.

-

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature FRANÇOIS-XAVIER GBRÉ in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 66–67.

-

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature MAYA KRINSKY in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 68–69.

-

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature PIERRE LEGUILLON in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 70–71.

-

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature BART LUNENBURG in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 72–73.

-

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature YUKI ONODERA in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 74–75.

-

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature JOHAN ÖSTERHOLM in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 76–77.

-

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature MAX PINCKERS in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 78–79.

-

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature JULIA SCHER in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 80–81.

-

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature SIMON & SIMONE in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 82–83.

-

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature MARKO TADIĆ in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 84–85.

-

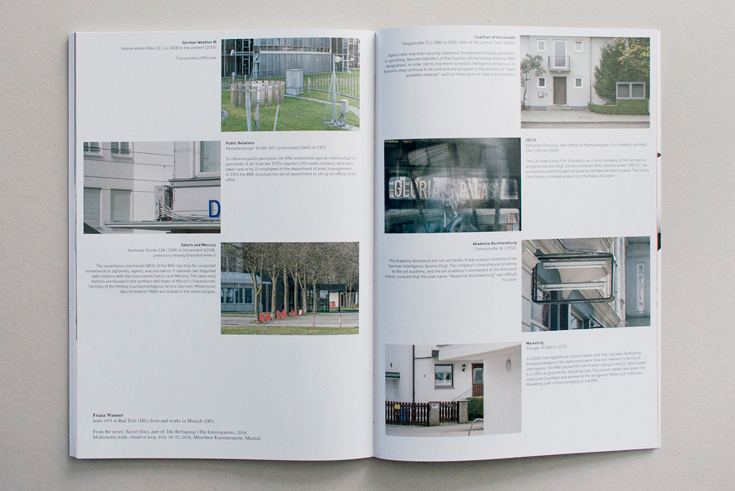

Künstlerbeitrag / Artist feature FRANZ WANNER in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 86–87.

-

Künstlerinnenbeitrag / Artist feature CARMEN WINANT in Camera Austria International 143/2018, S. / pp. 88–89.

-

Imprint

Publisher: Reinhard Braun

Owner: Verein CAMERA AUSTRIA. Labor für Fotografie und Theorie.

Lendkai 1, 8020 Graz, Österreich

Editor-in-Chief: Christina Töpfer.

Editor: Margit Neuhold.

Translations: Wolfgang Astelbauer, Dawn Michelle d’Atri, John Doherty, Nicholas Huckle, Lina Morawetz, Katrin Mundt, Wilfried Prantner, Marina Schumann, Andrea Scrima, Sabine Weier.

English Proofreading: Dawn Michelle d’Atri.

Acknowledgments: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Dina Al-Kassim, Jens Asthoff, Kader Attia, Lara Baladi, Véronique Besnard, Nahún Calleros, Michèle Cohen Hadria, Anthony Downey, Timothy Druckrey, Maria Eichhorn, Luigi Fassi, Karine Fauchard, Anne Faucheret, Duncan Forbes, Forensic Architecture, François-Xavier Gbré, Marina Gržinić, Claudia Gülzow, Grit Hachmeister, Sebastian Hau, Taco Hidde Bakker, Christian Höller, Susanne Holschbach, Omar Kholeif, Maya Krinsky, Sandra Križić Roban, Pierre Leguillon, Nicolas Linnert, Bart Lunenburg, Ben Mohai, Walter Moser, Yuki Onodera, Johan Österholm, Max Pinckers, Matthew Rana, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, Moritz Scheper, Julia Scher, Marika Schmiedt, Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Marko Tadić, Ana Teixeira Pinto, Fatoş Üstek, Mercedes Vicente, Claudio Vogt, Franz Wanner, Joanna Warsza, Sabine Weier, Carmen Winant.

Copyright © 2018

No parts of this magazine may be reproduced without publisher’s permission.

Camera Austria International does not assume any responsibility for submitted texts and original materials.

ISBN 978-3-902911-46-9

ISSN 1015 1915

GTIN 4 19 23106 1600 5 00143