Press information

Maria Hahnenkamp

Infos

Press preview

CRK+ Press tour 8.3.2019

9 am < rotor >

10 am Camera Austria

11 am Grazer Kunstverein

Opening

8.3.2019, 7 pm

Duration

9.3. – 26.5.2019

Opening hours

Tue – Sun, 10 am to 5 pm

Curated by

Walter Seidl

Press downloads

Press Information

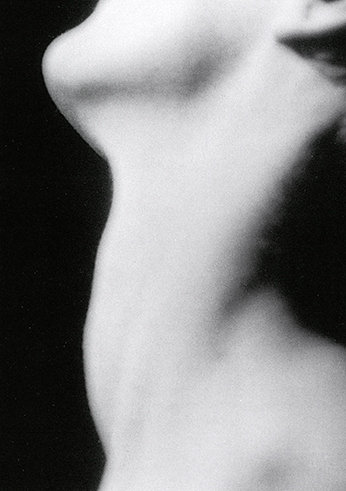

Maria Hahnenkamp counts among the generation of artists whose work has been shaped by feminist discourse and who have probed the medium of photography concerning this discourse’s structural conditions. Hahnenkamp deconstructs found media images featuring female typologies by granting the depicted women’s bodies but minimal presence in the image. This elusive presence is combined by the artist with self-staged photographs of body fragments and linguistic components. From this arises a critical analysis of the social and cultural reality of women in a post-structural world, in which image and language create reality through their representations and differentiations rather than merely rendering it. The works of the artist foster a dialectics between a female body language of absence and a passed-down cultural-historical ornamentation displaying gender-specific features: the female body is simultaneously visible and invisible, unattainable and coded. In her visual and material analysis, Hahnenkamp also makes reference to psychoanalytical moments of perception ascribed to the medium of photography. These content-related components pervade the artist’s work and are constantly redefining it.

For her exhibition at Camera Austria, Hahnenkamp developed a special dramatic composition that seizes on various forms of absence in the image, which are subjected to a process of gradual visualization. The artist investigates the possibilities presented by the photographic dispositif, with different visual regimes or shadow and mirror formations playing an essential role in the construction of (not only female) identity. In her photographic, textual, and haptic works, Hahnenkamp leads us through various reductions of the rendered material to a metalevel of photographic representation, thematizing not only the content of the images, but also their functioning and social use. Through intensified mediatic reproduction, she subjects the process of visualization to psychoanalytical introspection, illustrating the abuse of power evident in the circulation of pictures of women.

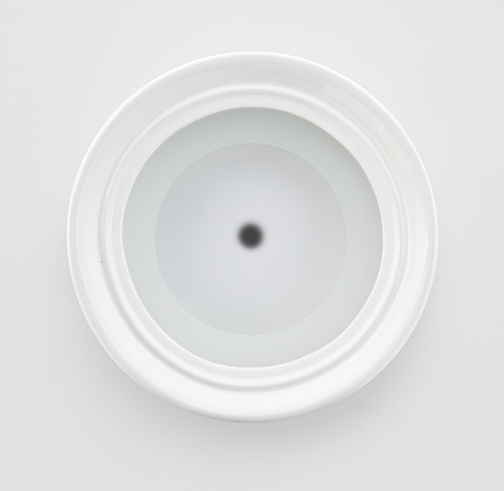

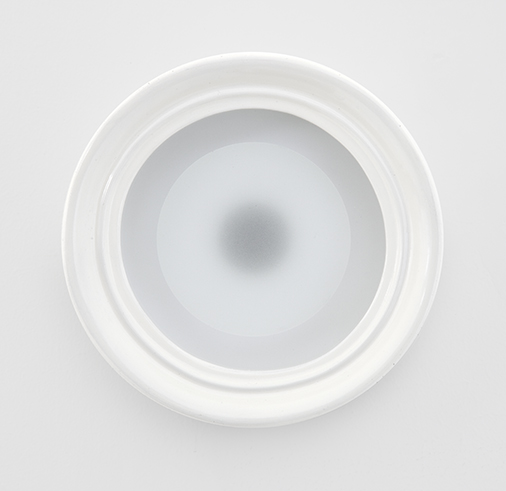

Marking the beginning of the exhibition are protophotographic visual formations that focus on the gaze and its primary function of recognition. In these works, Hahnenkamp references the foundations of the photographic representation of a fractured reality defined by the respective framing. The photographic apparatus is examined as to its functionality when round image/glass objects direct the gaze to black circles or holes of different sizes which refer to the photographic mechanism of the aperture and the intensity of incident light in each case.

The artist fathoms the photographic dispositif in its original function, which harks back to the camera obscura or pinhole camera and engenders focused perception in the creation of images; this has, since antiquity, led to a perspectival view, primarily for painting and ultimately also for photographic views. Hahnenkamp accomplishes this directing of the gaze through a drilled hole in the exhibition wall (“O. T.” [Untitled], 1995/2019), offering a view of the outside—the street—and framing it as a picture in the exhibition space using rocaille-like stuccowork. What appears to be a picture in the space—as a transient and flowing form—leads to an investigation of a reality that is transpiring every day before our very eyes. Next to it is an ornamental hole drilled in the wall which dissolves into an abstract line. A white whorl at the beginning of this wall has been mounted onto a mirror and makes the gilded reverse side of the object visible (“Kringel,” 2019). Here, Hahnenkamp is touching on the history of a language of form which became established in historicism and classicism and which experienced a transfer of meaning with the industrialization and capitalization of production processes and also during early modernism. The historically evolving controversy between ornamentation and abstraction, evoked predominately by men, then continued, yet “under different social and conceptual premises in the genderrelated [sic] discourse on the relation between ornament and femininity, of fashion and gender identity.”¹

The interpretational approach prevailing in many of these works draws on the psychoanalytical concept of Jacques Lacan, for whom the aspect of desire (désir) is tied to absence and moments of lack (manque).² For Lacan, desire “is neither the appetite for satisfaction, nor the demand for love, but the difference that results from the subtraction of the first from the second,”³ whereby it seems impossible to sate desire since it keeps reproducing itself. This causality chain of desire is demonstrated by Hahnenkamp in her dramaturgy of the represented and in a seriality of the fractured that has been defining photographic discourse since its very beginnings. The works thematize those moments of absence that have denied the presence of women for centuries, instead reducing them to the desire of the (male) body. The object nature of this view started being revised with the feminist demands of the 1960s at the latest, claiming woman as an autonomous subject. Hahnenkamp takes up such moments of desire for femininity in its current media-related state and subjects it to a photographic analysis by “keeping the imaginary transformation process going, as it were, between subject and gaze, subject and image, between representation and constitution.”4 She tries this out on different levels, removing from the viewer’s field of vision not only the picture of the woman but also the photograph exposed for this purpose.

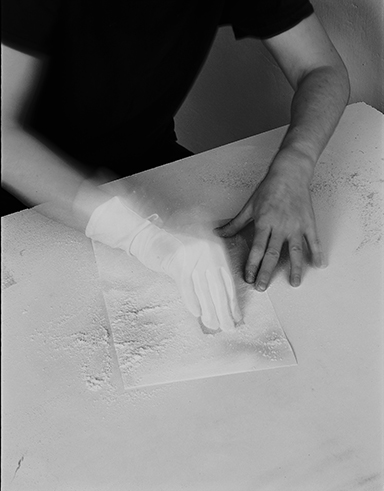

The latter is evident, or the artist engages in this denial, in the four-part work “O. T.” (Untitled, 1999), which is based on photographs, shot by the artist, of women in stereotypical body-care situations. However, Hahnenkamp erased the image content by sanding down the surface of the photographs, allowing a white, undefined gap to emerge at the image center, with only the edges still indicating what was once a photographic surface. Stitched together with a sewing machine and mounted edge to edge, she generates a field for the gap and lack that women represent as per Lacan, and that are ascribed a dual function in the symbolic order, as both mirror and object of male desire in equal measure.

Hahnenkamp’s pictures tell stories of violence against the feminine, or of its negation, and are executed through the medium of photography. By challenging the representational, in terms of both form and content, she formulates a critique of desire whereby the female body and the photographic apparatus, or its result, are scrutinized as to their basic conditions and laid bare. “If real femininity is formed according to the standards of its representation, as the story in pictures could demonstrate, then it is legitimate to criticise this power relationship by localising the material basis of photographic ideology in the thin coating of photographic paper.”5 In her photographic installations, Hahnenkamp catalyzes moments of desire, which, however, due to their potentially unlimited dissemination, cannot be redeemed. This artistic trope is especially evident along the end wall of the exhibition, where the flash of the camera is mirrored in a multipart photo series against a transparent foil curtain (“Regina / Fragmente,” 2008/2012). The works were created as part of a commission to portray the actors Regina Fritsch and Michael Maertens of Vienna’s Burgtheater. The photographic space as stage of representation and projection surface for desire is hollowed out here, with questions arising about its material conditions. It is at this juncture that Hahnenkamp transforms the exhibition space into a photographic mirror stage, which, along the lines of Lacan, serves the recognition of the individual as the self and as the other in the early months of life, which leads to simultaneous identification and alienation. “As a consequence of the irreducible distance which separates the subject from its ideal reflection, it entertains a profoundly ambivalent relationship to that reflection . . . (and) it will be unable to mediate between or escape from the binary oppositions which structure all of its perceptions.”6 The empty mirror thematically explores the position of the subject in front of and behind the camera, as well as the desire for the consummate likeness as resulting from narcissist projection. Here, Hahnenkamp pursues the question of how our longing and our conception of reality are shaped on an economic level by media-driven image worlds and how they mirror preformulated models of physicality.

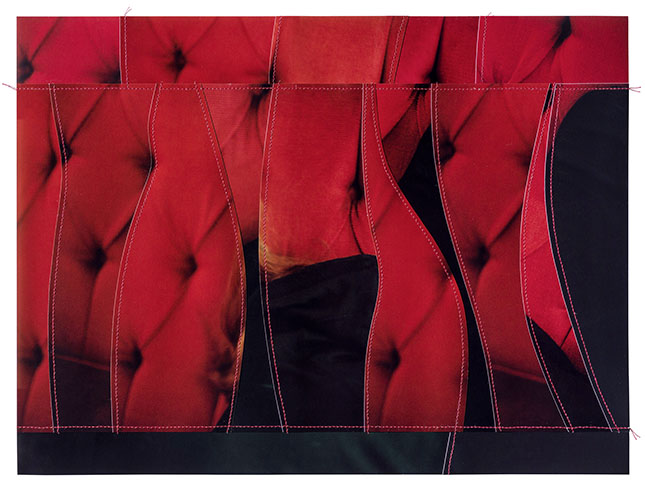

The already mentioned references to the ornamental state of the female body are broached by the artist in the works “Cut-Out” (2007) through photographic renderings of body fragments. Women’s bodies clad in everyday clothing nestle up to others and generate folds, with some of the bodies wrapped in foil tape, which are in turn furnished with text citations on the constitution of subjects cited by Judith Butler: “[Foucault] suggests that power acts not only on the body but also in the body, that power not only produces the boundaries of a subject but pervades the interiority of that subject. In the last formulation, it appears that there is an ‘inside’ to the body which exists before power’s invasion.”7 The bodies are resting on a plane of glass through which the photographs are taken, giving rise to a flattening effect that assumes a visual function a priori. Moreover, the images are overlaid with white decorative lines added digitally. At their side, the artist positions an over-embroidered white picture of a body fragment (“O. T.” [Untitled], 2019), with the ornamentation itself added as an act of violence against the violence to which female bodies are subjected by the media. Here, the artist connects the adorning function of the ornament with embroidery as an activity inscribed into the cultural history of women. Visible on the right are photographic set pieces of red seat upholstery—“Rote-Zusammengenähte-Fotos” (Red c-prints, sewn together, 1995)—with the gaze of the woman, her visage, cut away. The individual sections were sewn together, cultivating a gap as reference to the female sex. Rounding off this presentation is the video “V12/19” (2019)—newly compiled but originally based on “Diaprojektion 5a” (Slide projection 5a, 2008)—which shows body parts with an empty midsection. Hahnenkamp’s radical eradication of bodily presence in her processing of the mediatic image of women rebuffs their object status and underscores their existential determination as a socially contingent yet autonomous subject.

The sequence of images and objects, surfaces and materials, the presence and absence in the exhibition follows a dual strategy. On the one hand, Hahnenkamp spotlights in her artwork the void ascribed to women; on the other, she succeeds—through this lack—in posing the question of the deficit in women’s visibility and of the culturally and societally constructed context of meaning related to this deficit. The artist’s works rest on a denial of sensation-seeking curiosity. She merely allows set pieces of bodies to enter the picture, transferred to a state of limbo, so as to avoid reducing the image of women to a singular function. Hahnenkamp’s photographic studies open up the gaze by eluding the desire evoked by the media which is prone to engender emotions in a targeted way. It is on this note that the exhibition parcourse concludes with stone plasterboard (“O. T.” [Untitled], 2013) and unexposed photo paper (“O. T.” [Untitled], 2019), both of which introduce an absolute white emptiness into the space of photographic representation. The artist thus ties into the beginning of discourse within the exhibition, where the vacuum of existence is thrust into the field of vision as a fundamental condition for the creation of subjects.

Walter Seidl

¹ Rainer Fuchs, “Ornament: On the Content of Loss of Content,” in Maria Hahnenkamp, ed. Salzburger Kunstverein (Vienna: Schlebrügge.Editor, 2009), p. 118.

² See Jacques Lacan, Écrits: A selection, trans. Alan Sheridan (Abingdon: Routledge, 2001).

³ Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 38 (E, 287).

4 Translated from Silvia Eiblmayr, “Zur Dialektik der methodischen Wahrnehmung bei Maria Hahnenkamp,” in Maria Hahnenkamp (Salzburg: Fotohof edition, 1996), p. 12.

5 Christian Kravagna, “Die Frau, die Wahrheit und der fotografische Körper,” in Maria Hahnenkamp (Salzburg: Fotohof edition, 1996), p. 79.

6 Kaja Silverman, “The Subject,” in Visual Culture: The Reader, ed. Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall (London: Sage Publications, 1999), p. 344.

7 Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), p. 89.

Maria Hahnenkamp, born 1959 in Eisenstadt (AT), lives and works in Vienna (AT). Her solo shows included among others: “Werkschau XXI,” Fotogalerie Wien; Galerie Andrea Jünger (both Vienna, 2016); Kunsthalle Nexus, Saalfelden (AT, 2013); Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg (AT, 2008); Galerie Krobath Wimmer, Vienna (2007); Galerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris (FR, 2005); “Transparency,” MAK-Galerie, Vienna (2002). She participated in the exhibitions: “Women Now,” Austrian Cultural Forum, New York (US, 2018); Dommuseum, Vienna (2017); Zacherlfabrik, Vienna (2011); “The Power of Ornament,” Belvedere, Vienna (2009); “Erblätterte Identitäten – Mode, Kunst, Zeitschrift,” Stadthaus Ulm (DE, 2006). In 2007, Hahnenkamp received the Acknowledgment Award for Art Photography of the Republic of Austria, 1995 the Msgr. Otto Mauer Prize.

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.