Press information

Ines Schaber

Notes on Archives

Infos

Press preview

21.9.2018, 9:30 am

Opening

22.9.2018, 12 am

Duration

23.9.–18.11.2018

Opening hours

Tue – Sun, 10 am to 5 pm

Curated by

Reinhard Braun

On occasion of the exhibition the first three books of a five-part series will be published in cooperation with Archive Books.

In the scope of steirischer herbst 2018

Press downloads

Press Information

Since 2004 Ines Schaber has been pursuing in her work the idea of a “working archive.” In a series of case studies, texts, and artistic projects, she explores aspects of the archive, relating, however, not to the collecting and classifying of things, but rather to opportunities to probe, from the constellation of the respective archive, its forms of knowledge production: What are the archives lacking? Do we encounter false ascriptions? How do archives reference the non-visible, the undocumented, the disappeared—the many and diverse ghosts of archives? How do archives deal with the crisis of the document, of the documentary, and the crisis of truth production?

“I am starting with the assumption that the archive is not only a place of storage but also a place of production, where our relation to the past is materialised and where our present writes itself into the future; thus, accordingly, I understand the archive as a place of negotiation and writing” (Ines Schaber). Often, the point of departure is a certain image within an archive that catches the attention of the artist or reminds her of something, which she then researches (also in collaboration with other artists and authors) and around which she builds a story that cannot be confirmed because the people shown have already passed away and thus can no longer answer the open questions (“Unnamed Series,” “Dear Jadwa”). In other cases, there are contradicting statements about what is seen in the image (“Culture Is Our Business”), or the notes and comments originally created in connection with the images were separated from them again (“Picture Mining”). Ines Schaber visits sites where archives exist, or sites where pictures were taken that she “pilfered” from other archives for her work. Created in these places are landscape photographs dealing, for their part, with disappearance, with the disappeared; with how history is not representable, but actually a specter of the present as well. So questions arise about the wide-ranging circulation of images in various archives that provide different interpretations, or for which interpretive approaches must even be developed in the first place, and for which these questions are always relevant: How can they be mediated in our present day? What happens when the archival specters are reawakened? In this way, Ines Schaber develops an archival practice through which the many problems evoked by the archives themselves become part of a process that advances her artistic practice. As such, Ines Schaber does not work primarily through or with certain archives, but rather transforms archival practices into a practice of artistic research.

For the exhibition at Camera Austria, her first institutional solo exhibition in Austria, the artist is creating new connections among the following series of recent years: “Culture Is Our Business” (2004), “Picture Mining” (2006), “Unnamed Series” (with Stefan Pente, since 2008), and “Dear Jadwa” (2009).

Culture Is Our Business

In January 1919, the photographer Willy Römer from Berlin shot one of his best-known pictures of the German revolution: “Strassenkämpfe in Berlin” (Street Battles in Berlin). Ines Schaber’s work “Culture Is Our Business” traces this image through various archives, following the life path of the photographer and a labyrinth of usage rights. In the process, she comes across two very different archives: the online image archive belonging to Corbis and the Agentur für Bilder zur Zeitgeschichte, a private contemporary history archive in Berlin. Neither organization is still in existence today, though for very different reasons. Although Willy Römer’s photograph has been in the public domain for years now, both archives exploited the image. The legal successor of Corbis, Unity Glory, a company belonging to the Chinese Visual China Group, is still doing so today, whereas the collection of the Agentur für Bilder zur Zeitgeschichte was sold in 2009 to the photo agency of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. We can only see the street fighters from behind—crouched behind giant rolls of paper, waiting to shoot. They come from different classes—workers, soldiers, young and old—but are united against the imperial troops in order to defend the printing company that had just been taken. According to Corbis, however, the imperial troops were defending the city against insurgents—an inversion of history, which turns the image into a document of contrary meanings. At the end, Ines Schaber pens a letter to Bill Gates: “I was surprised that these fighters had found a way to smuggle themselves into your limestone mine, able to continue fighting from within. Buried but still alive and acting like ghosts—always ready to fight, even if you hide them deep in the earth in a place hard to find. … Are you sometimes afraid of them haunting you ? It must be like this. If I were you, I would try to let them go.” Hence, the photograph by Willy Römer opens up a space that potentially remains hidden from the (Corbis) archive itself and inaccessible to the rules of its origination and order. Maybe it is vital to first search, within archives, for that which cannot be found therein. And perhaps what is found, within that which cannot be found, is the opportunity to call the specters by name. And maybe something like a truth (of history) flares up in that moment where the specters are given the act of speech.

Picture Mining

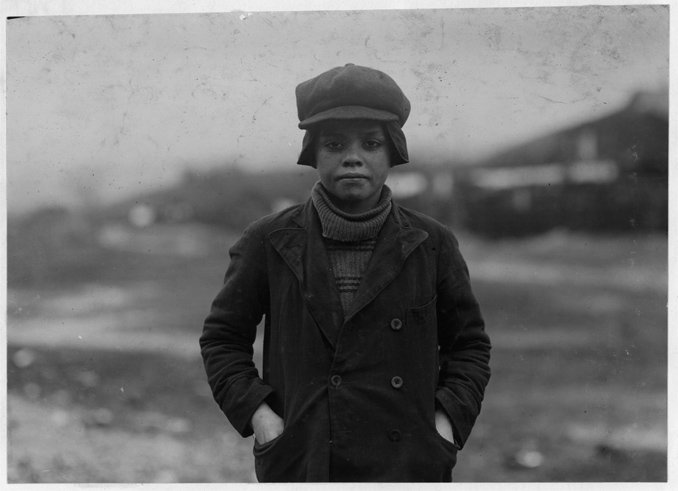

In January 1911, Lewis Hine was commissioned by the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) to photograph work in a coal mine in Pittston, Pennsylvania. The pictures were taken on two successive days and focused on a boy named Angelo Ross. We know this because Hine labeled his photos and also added comments. Yet in almost all of the archives containing photographs by Hine, these textual annotations are missing. In Butler, Pennsylvania—not far from the place where Hine documented the child labor of capitalist modernism—there is one of the largest underground archives in existence today. Stored in this former limestone mine are also many pictures by Lewis Hine, including some of the shots captured in Pittston.

Whereas in earlier times resources for industrial production were mined here, today the site houses the federal archives of the US Department of Defense, the social security data of all US citizens, and also images, films, and documents from many corporations like Disney and MGM. And since the Corbis Archive was situated there before its acquisition by Unity Glory, the mine was also the “home” of the pictures of Angelo Ross for a while. Similar to Willy Römer’s insurgents, who today can no longer be sure for which side they were actually fighting, it has also become uncertain as to which history Angelo Ross belongs: that of American documentary photography, that of political enlightenment and civil rights movements, or that of the decline of modernist industrial production? Basically, the pictures of Angelo Ross can be purchased for almost any imaginable purpose, with the post-industrial meeting the post-factual, the archival documents becoming specters of ephemeral meaning that is constantly shifting for us. Ines Schaber took landscape photographs near the mine, which also equate to a spectral documentation: they show a place characterized by the demise of the economy, a post-industrial landscape that appears to have fallen out of time and itself become a ghostly terrain. “Picture Mining” is pervaded by questions about what images are even capable of showing and which effects their representations may have: Do we still today believe, as Lewis Hine likely did, that whatever is seen in the images can change the world?

Unnamed Series (with Stefan Pente)

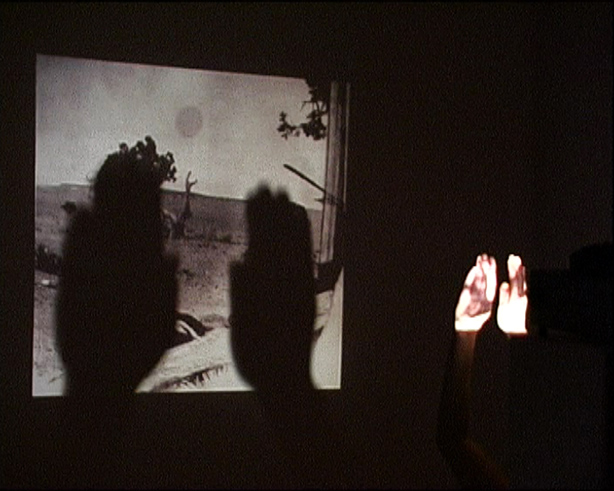

In April 1923, Aby Warburg, who with his “Mnemosyne Atlas” offered decisive impulses to the cultural sciences of the twentieth century, gave a lecture at the sanatorium in Kreuzlingen in Switzerland about the Hopi Indian serpent ritual, which was said to verify his mental fitness, for he had been in treatment there for schizophrenia since 1921. In 2008, at the studio of artist friends in New York, Ines Schaber and Stefan Pente, with whom Ines Schaber realized this project, saw a contact print by the photographer Karen Peters showing pictures of the Palace Hotel in Santa Fe that had burned to the ground in 1930 and has been converted several times since. It was in this hotel that Aby Warburg met the Hopi priest Cleo Jurino in 1898, who drew the ritual for the historian during this encounter.Warburg expressly did not want the lecture at the sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, nor the visual material used there, to ever be published. After his death, however, the documents were reviewed as part of his estate and, as was prone to happen, the images suddenly appeared decades later, printed in high gloss in hardbound books and possibly even shown in exhibitions. How, ask Ines Schaber and Stefan Pente, should we look at pictures that never should have been taken and that, as such, never should have been seen? What experiences were they associated with, which, however, were suppressed by Warburg himself? Today they can never be unseen, can never be simply made to disappear again. What were they originally meant to represent or substantiate? What do they represent or substantiate today? In a letter to Aby Warburg, Schaber and Pente posed these questions. It was the handling of these photos that they wanted to discuss—an impossibility—with Aby Warburg. Whereas in the case of Willy Römer and Lewis Hine something disappeared that substantially determined the meaning of the pictures in the moment of their genesis, in Aby Warburg’s case something suddenly became visible that was really meant to remain invisible. But what should be done about this state of excess visibility? We might surmise that something is withheld from the archive because it appears to contradict its order, because it might bring disorder to the archival order. According to Warburg, he himself was not able to speak about the ritual as long as he was healthy—only in a state of insanity—which is why he later forbid the publication of these materials. “You never could speak about what you experienced under the vast western sky. Something must have struck you as being unspeakable. But how can one create ways to speak the unspeakable, address the impalpable?” (Pente and Schaber).

Dear Jadwa

In 2008, the art gallery in Umm el-Fahem, Israel, showed an exhibition thematizing the founding of a photographic archive, with which it had commissioned the art historian Dr. Mustafa Kabha and the photographer Guy Raz: “Memories of a Place: The Photographic History of Wadi ‘Ara, 1903–2008.” Up to this point, no photographic collection on Arab culture had existed in Israel. The concept of the archive concentrating on the site and not on the identity of what is shown or of the photographer formed the point of departure for the work “Dear Jadwa.” “What are the different points of access in establishing a visual history of Palestinians?” and “What should this facilitate?” were the main questions asked of the archive in Umm el-Fahem. What would be the potentials and what would be its limitations? After Ines Schaber had already gained experience with conducting research in Western archives, she ultimately found—in the Matson Collection of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, after having searched there for photographs from the region—two group photos of the “Arab Ladies’ Union Meetings” at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in the year 1944. Between 1881 and 1934 The American Colony resided in Israel, a Christian sect whose members had emigrated to Jerusalem from the United States and Sweden. By 1944, however, most members had already left the country again, except for Eric Matson and several other photographers. These two photographs are remarkable because hardly any other documents of the political organization of Palestinian women exist, despite the “Arab Women’s Association of Palestine” already having been founded in 1929. No one in Umm el-Fahem was familiar with the photographs or knew any of the women pictured there. However, a certain woman is seen at the center of both pictures; Ines Schaber calls her Jadwa and has meanwhile learned that her name is Huda Sha‘rawi.“I am left with one last question, the question I have started with: where did you imagine and where would you wish this image to be shown? Did you think that it could help facilitate or provoke a congruence between memory, actuality, and language? Maybe you can find a way to get in contact with me. Yours truly, Ines” What had Jadwa done there, what were the women discussing, and why was this group photo even taken? What are the demands placed on us today by these women?

The archive is here—as in all projects mentioned—quite obviously not the subject of research, but rather the starting point for a series of questions that the archive cannot actually answer itself. The archives do not appear to be representative—but representative of what exactly? Are there necessary illegitimate questions asked of the archives that might be able to uncover equally necessary illegitimate and suppressed knowledge, similar to how Michel Foucault phrased it in his genealogy? The hope of conformity among memory, reality, and language with which this conformity might be expressed is tied to the hope that a voice from this archive might reach into the present day, that the voice of a specter might engage with us, with the artist, and answer the countless questions posed by all of the photographs sunk, isolated, commercialized, fragmented, renamed, marginalized, or forgotten within the archives.

Reinhard Braun

Images

Publication is permitted exclusively in the context of announcements and reviews related to the exhibition and publication. Please avoid any cropping of the images. Credits to be downloaded from the corresponding link.